As his new book of Polaroids is published, Jack Lueders-Booth talks about creating a humane portrait of inmates at a women’s prison in Boston during the 1970s

Jack Lueders-Booth appears on my screen wearing a red jumper and crinkly brown tweed jacket, surrounded by books and neat piles of printed materials in his charming Boston home office. “I’m not quite in order,” the 88-year-old American photographer and former Harvard professor says. “I’m just waking up. As a matter of fact, I was up all night working on a paper.” He smiles when I say I haven’t slept well either; “We can be not very lucid together.”

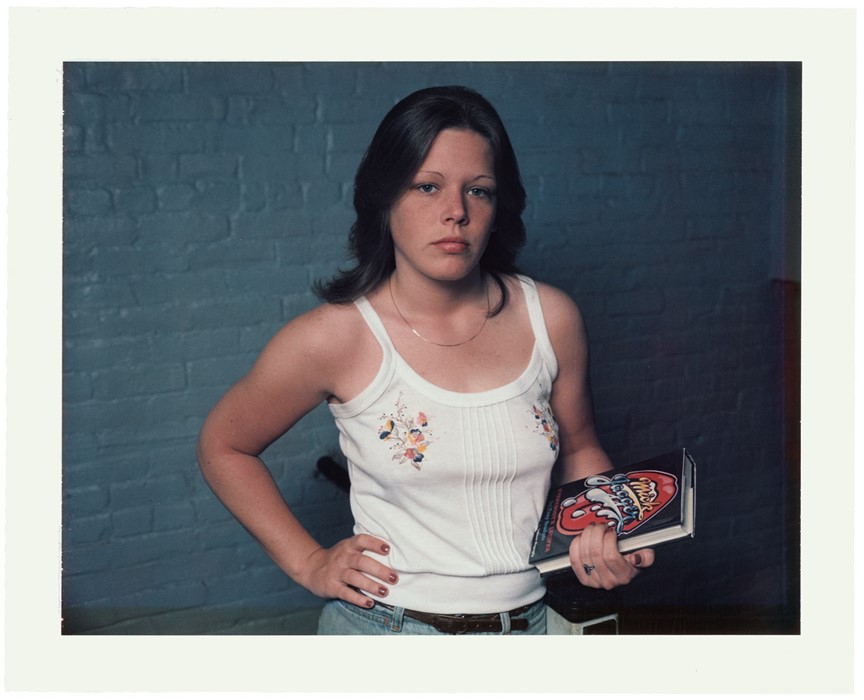

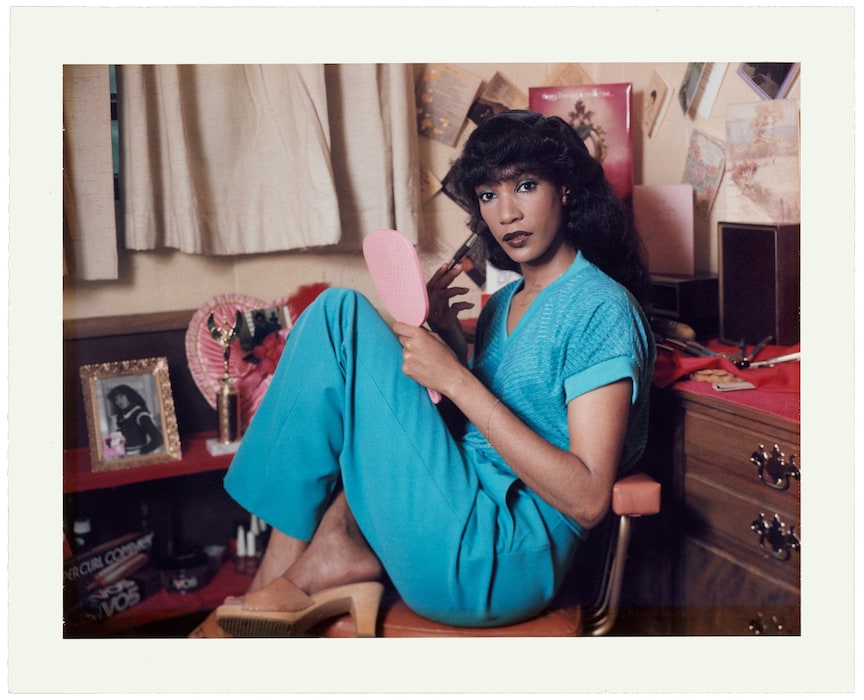

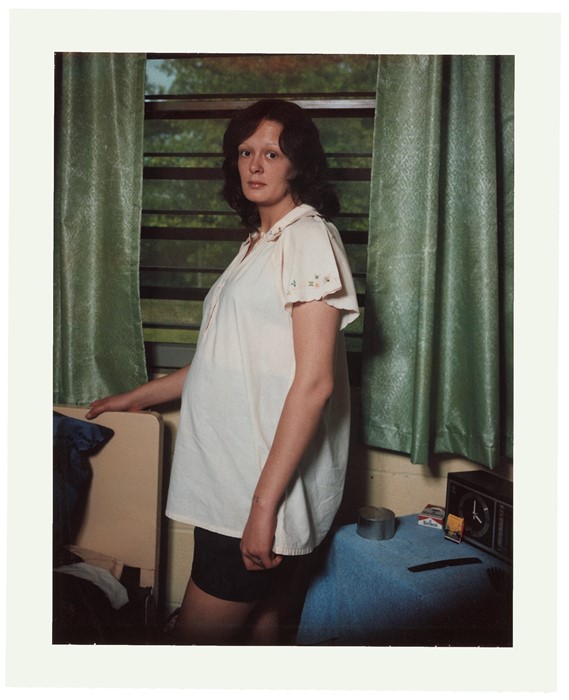

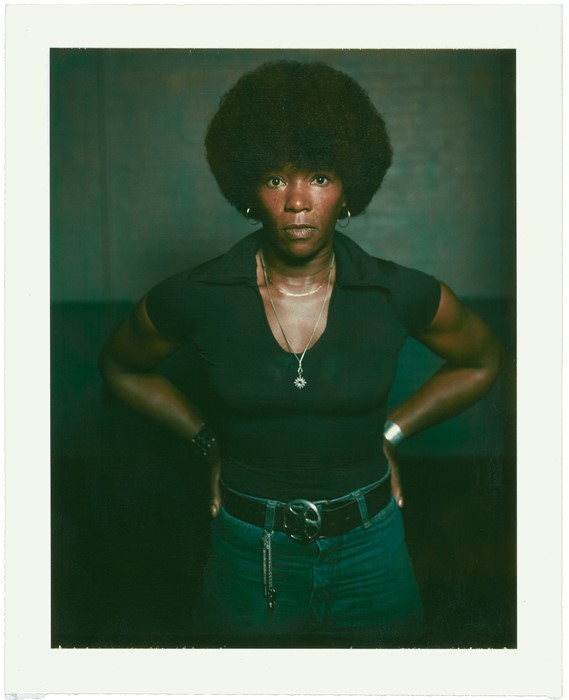

Lueders-Booth’s work as a documentary photographer has brought him into the fold of outsider communities over several decades, photographing chronically ill people, motorcycle crews, and families living on the dumps of Tijuana. We are here to discuss a series of Polaroids he shot in the 1970s at MCI Framingham, a women’s prison in Boston, which have been published for the first time in a new book from Stanley/Barker. Pairing dignified portraits of over 50 inmates with raw personal stories and poetry, Women Prisoner Polaroids is a testament to Lueders-Booth’s ability to cast a human gaze upon people who have found themselves in incredibly difficult circumstances.

Lueders-Booth never set out for the project to be a book; in fact, he never intended to shoot the women at all. He first went to MCI Framingham as part of his master’s degree at Harvard. “I had a specific idea in mind, and that was to teach in photography programmes in institutions of confinement, as a way of boosting morale,” he recalls. “I found in my own life that photography did me a lot of good in that respect. It was intellectual on the one hand, but primarily, it was a craft you could do with your hands. Anyone could do it and derive enormous pleasure from it. That was my proposal to the school, and they accepted it.”

When Lueders-Booth arrived at the prison in 1977, it was undergoing a “normalisation experiment” which sought to offset the psychological effects of incarceration. Cells were furnished by inmates with home comforts, and neither prisoners nor faculty wore uniforms. The guards themselves were primarily criminal justice students from Northeastern University, and the environment was such that everyone interacted more or less as peers. “You couldn't distinguish a guard from an inmate unless you knew who they were,” Lueders-Booth recalls. “I had no idea what a prison was like and I was actually scared when I first went, but it’s like so much in life – the more you [become acquainted with] something, the more normal it becomes.”

Early visits saw the photographer and his daughter Laura, who was 18 at the time, transform 19th-century jail cells into darkrooms with the help of volunteer inmates. “Laura was the same age as the majority of the prison population,” he remembers. “I was in my early forties as a white male in this prison and I think that helped me a lot at that time.” Wanting the women to fall in love with photography the way he did as a teen, watching his dad develop photos in their family bathroom, Lueders-Booth started lessons in photograms and the darkroom, later graduating to pinhole cameras made with cereal boxes and finally cameras with lenses. “It was a magical thing when they [developed images] the first few times,” he says. “It’s still magical for me and I’ve been doing it for decades.”

Lueders-Booth only started taking the women’s portraits as a way of teaching them to use a camera. Slowly, image by image, a documentary project began to take hold. “The women were compelling in many ways; their backgrounds, their assertion of certain values,” he says. “I became quite fond of them, really, as people.” Lueders-Booth only intended on working at the prison for a year, but these friendships meant he stayed on for an entire decade. “I was jokingly referred to by some administrators as the high school photographer,” he says.

While these images are only being formally published now, the initial idea to make them into a book came in the 1970s from a friend of Lueders-Booth’s, the legendary photographer Bruce Davidson (he also suggested the women narrate their images with their life stories). Lueders-Booth borrowed some recording equipment from Harvard and set up space in his prison office. “I said to the women, ‘Listen, I am recording life stories or anything you want to put on tape for eternity’,” he remembers. “‘Just whatever you want to tell the world. Here’s a microphone, and here’s your chance.’ Until then, we never discussed in detail why they were there.”

Collated anonymously in the back of the book, the accounts shared in that office are full of female rage and vibrant resolve, with personal stories of domestic violence, drug abuse, sex work, police brutality and murder. “I sat listening and I just was aghast at some of the things they’ve endured,” says Lueders-Booth. “These women had been through some truly hard times.” In reading their stories, an understanding of the circumstances that could lead to even the gravest of offences is offered, such as one woman who killed her abusive boyfriend; “I do not feel sorry for defending my body ‘cause I’m a woman and I have had it. I have had it.”

“In all of my work, an ambition I have is that people will come to recognise that a person’s most obvious dimension is not their most significant dimension,” the photographer says, when asked what he hopes others will take away from the book. “Things are not always as they appear, and generalisations and assumptions about certain populations are largely unfounded.”

Women Prisoner Polaroids by Jack Lueders-Booth is published by Stanley/Barker, and is out now.