Focusing on his father – who served a prison sentence for drug dealing and attempted murder – Abdulhamid Kircher’s new book Rotting From Within is an unflinching exploration of family and hereditary flaws

Abdulhamid Kircher was 17 when he became reacquainted with his father after more than ten years apart. During that time, Kircher and his mother fled an abusive home, relocating from Berlin to Queens, New York, while his father Sedat served a prison sentence in Germany for drug dealing and attempted murder. It was only around the time of their reunion that Kircher began taking photographs, with the camera offering a means of access to both the father he never knew and those parts of himself he’d unwittingly inherited.

Over the next ten years, Kircher spent his summers travelling between Germany and Turkey (the country of his father’s birth), documenting the evolution of their relationship while inadvertently revealing an insidious cycle of patrilineal trauma embedded across multiple generations of his family. The resulting body of work makes up Rotting From Within, a raw and unflinchingly honest project of some 400 images that lays out the impossible complexity of family in all its tangled, fraying beauty.

“A lot of the relationships that I’ve built over the years stem from photography,” explains Kircher, who, at 17, was attending high school in New York and channelling a formative interest in Diane Arbus with his own street photography. “At the time I met my dad, I was very much obsessed with trying to get deeper into every little situation. If I met someone on the street, I would try and go home with them and see if I could take pictures of them naked or having sex or doing drugs.”

With his ties to Germany’s criminal underworld, Sedat proved the perfect gatekeeper for his son’s photographic ambitions, providing him access to a world that would have otherwise remained beyond reach. “It was almost like, all of a sudden, I was at the top of the food chain,” explains Kircher. “I could just be like, ‘I want to photograph this guy smoking crack, can you take me to his house?’ And it would happen within a day.”

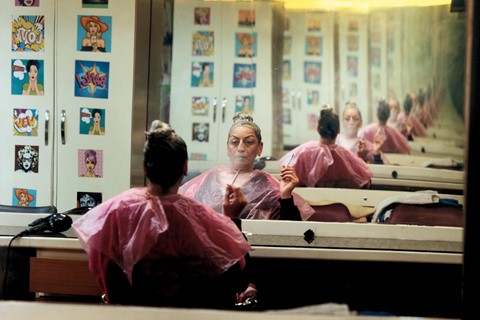

In the book’s opening chapter, Kircher offers a glimpse into the intoxicating appeal of his father’s line of work, with dingy, candlelit rooms as the setting for all kinds of nefarious activity. In one photograph, a figure stripped to the waist stands with his back to the camera as he fixes a silencer to a pistol, a second tucked into his waistband. In another, a man’s face looms from the enveloping darkness, lit red by two candles, his expression somewhere between pain and ecstasy as he inhales from a crack pipe.

“I became so obsessed with taking these photos,” says Kircher, for whom photography, at least in the early days, resembled a pursuit of life on the peripheries. “It brought me such happiness that I automatically associated that happiness with this new relationship with my father.“ Beyond their initially joyful reunion, however, it didn’t take long for Sedat’s demons to emerge. “Every year that I came back I realised how dark his world was and how stuck he was and how terrible of a person he could be.”

It was in these moments that Kircher began connecting aspects of his father’s character to his own. “Rotting from within is this uncontrollable aspect of yourself that stems from your father,” he explains. “Even though I didn’t grow up with him, I started having similar tendencies.” Later in the book, Kircher travels to his paternal grandparents’ house in Antalya, Turkey, documenting his time on the road with photographs taken from bus windows and busy intersections. Set in the bucolic countryside, these photographs are worlds away from Berlin, and yet, similar themes of fatherhood and hereditary flaws persist.

In one photograph, Kircher’s grandfather lies in a hospital bed with Sedat by his side, an unmistakable look of devotion in his eyes as he kisses his father’s arm. Later, Kircher’s grandfather is pictured with a slaughtered lamb at his feet – a traditional sacrifice carried out by the head of the household following a near-death experience. Kircher’s diary entries that conclude the book explain that his grandfather was unable to carry out the sacrifice, with his sons stepping in to finish the job. In that moment, he looks down at his trembling hand as though seeing it for the first time, sensing his encroaching mortality.

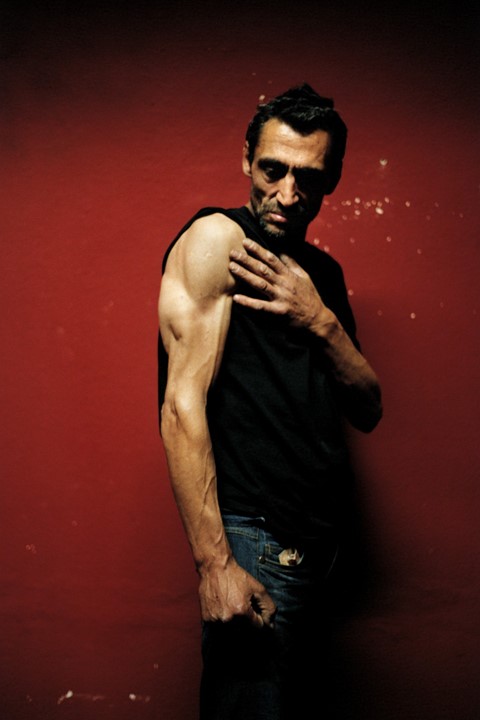

By the end of the book, Sedat’s own health is deteriorating and the once fearsome man suddenly appears vulnerable, like a small boy, pictured asleep, in hospital or seeking comfort from his girlfriend. “You can see him getting more depressed as his body starts breaking down,” says Kircher. “That’s the beauty of making work over a decade – you see these changes that only appear with time.” In spite of their ten years spent together, this project yields no neat conclusions on Kircher’s relationship with his father; it remains amorphous, fragile and in flux. “I don’t think it was ever about forgiving him for what he did to my mum. Ultimately the work allowed me to understand him and the environment he grew up in and what made him the person he is. I don’t know exactly what it did for me – that’s probably something I will always be working on.”

Rotting from Within by Abdulhamid Kircher is published by Loose Joints, and is out now.