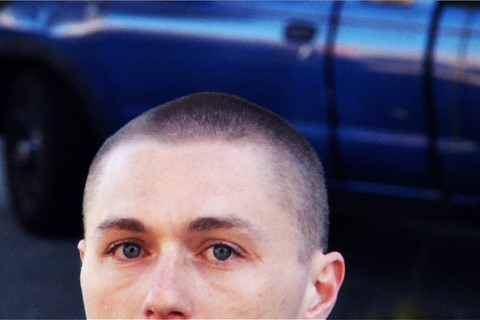

Before William Strobeck fell in love with skateboarding, he fell for the style surrounding it. As a young teenager growing up just outside Syracuse, a city over 200 miles north-west of Manhattan, Strobeck vividly remembers the moment he came across a photograph of pro American skateboarder Natas Kaupas in a magazine during the 1980s. “At the time, skaters had long bangs like Tony Hawk, but I saw this photo of Natas and he had this really cool haircut, with spiked hair and blonde tips,” Strobeck recalls. “I didn’t see anybody else like that, so I made my aunt take me to a place and get my hair bleached in the front.” Newly minted with peroxide blonde hair, triple XL shirts, and baggy jeans, his aunt bought him his first skateboard while he was a student in high school. “I really got into skateboarding at first for the look of it,” he reflects. “And I’m very visual as a person anyway. Skaters just look cool, there’s something about it.” The rest, as they say, is history.

Now, as one of the most prominent and influential skate videographers working today, Strobeck himself is responsible for much of “the look” of modern skateboarding. And it’s significant that his entryway into that world was via an image of Kapaus; lauded as one of the first true professional street skateboarders, he is partly responsible for shifting the sport away from purpose-built skate parks and into the urban environment during the 80s. Today, Strobeck shoots almost exclusively on the streets – mainly in New York City, where he has lived for the past two decades – and that urban backdrop is an essential part of his oeuvre, with all of its raw energy and chaos.

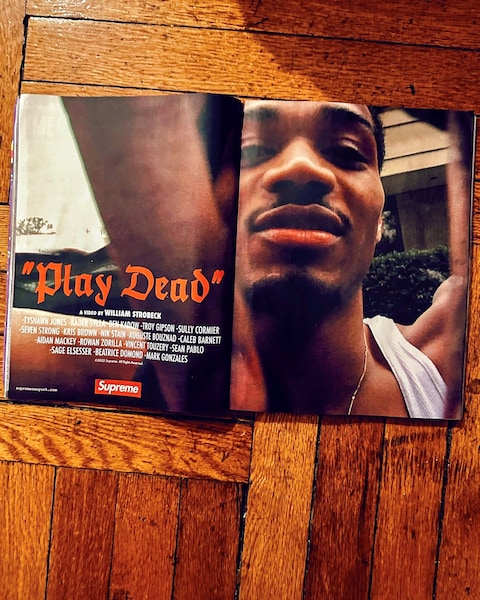

Across his feature-length skate videos for the American streetwear behemoth Supreme – which rack up millions of views on YouTube, sometimes stretch to over an hour long, and are released roughly once a year – and his videos for Violet, the skate company he launched in 2022, Strobeck has shaped skateboarding in his image, with his original, distinctive eye for colour, composition, character, and music. He has a killer knack for creating iconic images, many of which include either fire, blood, or baby-faced beauty.

Historically, skate videos showcase tricks and technicalities, but Strobeck favours the in-between moments; he captures the grimaces of skateboarders after they bail in close-up – the teenage girl’s answer to a fallen angel – altercations with unwitting pedestrians and security guards, the trickle of blood above a sanguine-red waistband of Supreme-logoed briefs, or the tender embrace of young lovers on the streets of Manhattan. His videos, heavy on naturalism since the characters in them are actually real, often err into the realm of mumblecore independent films, such is his attention to the subtle, fleeting peculiarities of street life. Strobeck is known as a skate videographer, but really, he’s a filmmaker who just happens to film skateboarding.

“Some people wouldn’t even call a skate video work because it’s just skateboarding,” he says. “But dude, those are the hardest videos to make. It’s all real, real time, [with] real things happening on the streets. [When] you do a movie, you have schedules, actors doing the job – two months and you’re done. I’m talking about two and a half years of being in the streets, getting kicked out of a spot over and over, cops coming. There’s a lot of little wins in those videos to get to one big goal.” Once finished, these films are often promoted lavishly by Supreme, which was bought by VF Corporation in 2020 for an eyewatering $2.1 billion; Blessed (2018), a video dedicated to the late pro skateboarder Dylan Rieder, was “promoted like it was a fucking Scorsese movie”, says Strobeck, with posters plastered all over New York, adverts in the New York Times, and a raucous premiere.

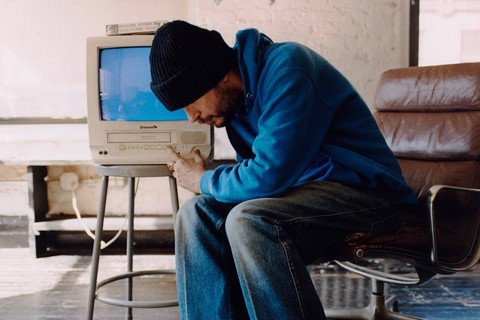

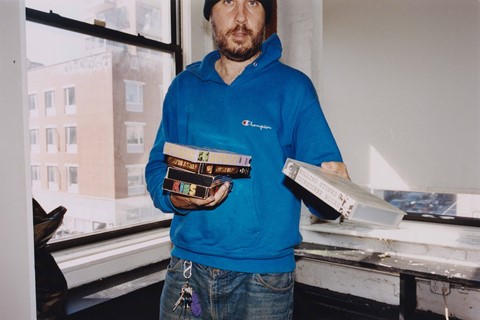

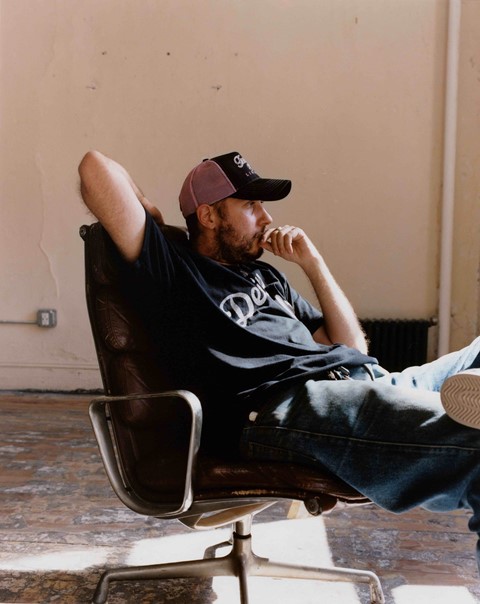

Today, Strobeck is speaking over Zoom from his new studio in Chinatown. His East Village apartment, once so iconic in his work, may now take a backseat (he regularly posts photos to Instagram of skateboarders, artists and downtown New York personalities in his living room, and in 2019, exhibited a life-sized model of his apartment in Manhattan’s Milk Gallery). “I’ve been in a studio apartment with all my shit around me, growing over me like nature does. I was just sick of it. But I’m really happy here. It’s literally so beautiful,” he says, flipping his phone camera around to survey the studio’s vast, empty rooms, which are dappled in sunlight. “It’s everything I’ve ever wanted. It’s a new vibe for the new era.”

Growing up in Syracuse, Strobeck was enmeshed in the skateboarding and hardcore music scenes; he lived with his aunt and grandmother for much of his teenage years due to his mother’s struggles with schizophrenia. At age 17, after moving to Philadelphia – “there was real raw fucking street shit going on there” – he began to make videos for the skate company Alien Workshop while doing pizza deliveries on the side. Then, after a relationship ended in Philadelphia, he made the move to New York – at age 24 – and never looked back.

“I just got taken over by this place in a way that I can’t explain,” he says, recalling the vibrant atmosphere of Manhattan in the early 2000s. “There was something about being here. There was a scene of 180 people who would find each other every night, and there was no way of communicating pre-internet, so it was low-key, word of mouth. I swear to God, I partied for ten years straight till four in the morning every night. I fell in love with all different types of people, not just skaters.” This included it-girl and actress Chloë Sevigny, a close friend of Strobeck’s, with whom he collaborated on a music video and a short film, and who has modelled for Supreme – and appeared on their T-shirts – numerous times.

Strobeck first visited Supreme’s original Lafayette Street store in New York during the 90s, recalling that it was “a vibe”. Launched by James Jebbia in 1994, Supreme’s humble, underground roots are difficult to picture given its current cultural ubiquity (Jebbia maintains that, despite its popularity, Supreme will always be cool). But in 1995, Harmony Korine and Larry Clark’s Kids – a seminal coming-of-age film about sex, skateboarding and HIV – starred many skateboarders who actually worked in Supreme’s New York store.

Today, Strobeck cites Clark as a big influence, namechecking Tulsa (1971) and A Perfect Childhood (1995) – two photo books that were hugely controversial upon their publication – as his favourites. Strobeck’s skate videos for Supreme can feel like the 21st century’s answer to Kids; just as Clark once did, Strobeck follows skateboarders around Manhattan, capturing the mundane, daily goings-on of their rag-tag community. Naturally, his other influences include Ari Marcopoulos, Jim Goldberg and Nan Goldin – “Nan photographed a real raw time in New York” – with their unfiltered documentation of their own lives and communities.

After publishing a series of skate videos and music videos online in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Supreme came calling, asking Strobeck to create a commercial for them (he credits Mark Gonzales, a larger-than-life skateboarder, artist, and early collaborator, as having “popped off” – AKA launched – both his and Spike Jonze’s careers). Shot on his signature fish-eye lens, Buddy (2012) features a baby-faced, 13-year-old Tyshawn Jones and Jason Dill cruising through New York effortlessly on their boards, and is bookended by two brief, humorous interactions with pedestrians – a style that would later become his hallmark. (In one, a stranger admits that he “smokes a little crack every now and then,” to which Dill replies, “Hey, I used to too. It’s not a big deal.”)

“When I started making my own videos, I took a bunch of footage that I had lying around and started making stuff that represented what skateboarding felt like to me,” says Strobeck, of his instinctive, poetic approach to filmmaking. “It started getting picked up through the internet and people were talking about it.”

After the success of Buddy, which clocks in at 50 seconds, Supreme commissioned Strobeck to make their first ever feature-length skate video. Cherry (2014), a 38-minute video capturing Tyshawn Jones, Sage Elsesser, Sean Pablo and others skating around New York (with cameos from musicians Tyler, the Creator and Earl Sweatshirt) cemented Strobeck’s status as a pioneer of the medium. “Everything I ever wanted to do was put into that video,” he says today. “But I also had the biggest streetwear company backing me, and they had never put out a skate video. So it was my first video, their first video, and the crew – the kids – that was their first video. That mix alone is like dynamite. I just had a feeling it was going to pop off, and it did.”

Opening with the woozy sirens of Cypress Hill’s stoner anthem I Want To Get High, Cherry encapsulates all the raw energy of street skateboarding, with brief interludes of mischief, mayhem and astonishing beauty. Whether shooting the evening light delicately outlining a young man’s profile, blood gushing from a head wound, or a skater boardsliding a handrail at high velocity, Strobeck’s camera lingers affectionately on these young skateboarders’ athletic forms, capturing their graceful, balletic movements in slow motion.

Today, Strobeck remembers Cherry nostalgically as a watershed moment of calm before the storm of success. “That’s the power of the internet, you’ve got people all over the world talking about you and you don’t even know who you really are yet,” he says. “These kids were 14, 15, 16 years old at the time. It’s such a special moment in life, you’re just being who you are. Youth is wasted on youth. You don’t even know it until you look back on it.”

Part music video, part fashion film, the colours in Cherry are painterly and rich (they were achieved by Tom Poole, the colourist behind films including Drive and The Place Beyond The Pines). “Most of Cherry is black and white, but if you see any colour, it’s really smoky and blue,” says Strobeck. “Tom is just really magical.” The soundtrack is a worthy addition to any playlist; Cherry mixes rock, classical and hip-hop by The Cure, Chief Keef, and INXS, adding eclectic shades of high drama to the action unfolding in the video.

“Growing up, music was everything in skate videos,” he recalls. “I would record the music off the TV and listen to it because I was just obsessed with skating that much, it took over my life.” These days, though, he is more jaded. “I care so much about music but [with] those early videos, I wasn’t even having to think that much. It just was a feeling,” he says. “Now I have to really think about it, and there’s music rights and all this shit which I didn’t have to deal with at the beginning. At this point, I don’t even know if I like music. I’ve turned to regular radio music now because I feel like that’s punk.”

Today, alongside his work for Supreme, Strobeck puts a good amount of energy into Violet, the skate company he launched a few years ago after discovering a new wave of young skateboarders in Philadelphia and New York. “Everyone is so cool, unique and has their own sense of style,” he says of the motley crew he has assembled. “They’re all different, but they feel like family.” One member is Efron Danzig, an up-and-coming model who is trans (she recently appeared in a majestic shoot for Dazed, skating around the streets of Paris). What does Strobeck make of skateboarding’s slow inch towards inclusivity? “When I first started skating, it was a male, macho time,” he says. “But the whole thing about skating is that you can be who you feel you are as a person, it’s an outlet for all the feelings you have inside. It’s nice to see everything grow in a way where every person can feel like they have their place in skateboarding and in the world as a whole.”

For years, Strobeck has expressed a desire to make a narrative feature film, but nothing has come of it yet. “I actually am asking myself now, am I gonna just say this in every interview until I’m 90?” he laughs, stalling the conversation. “I don’t know. I’ve had ideas.” But perhaps a film is a futile exercise; by honing in on the microscopic details of human behaviour, and elevating skateboarding into an art form in the process, Strobeck’s videos hold more honesty – and more life – than fiction could ever achieve. “I care so much about my existence here on earth and what I get to do, and I’m pretty lucky to have found my passion and niche of what I want to showcase as mine,” he says. “Sometimes I’ve questioned my brain – like, is this even cool to me anymore? But life is pretty crazy. Some people are lucky enough to be able to do something with their life that they love. I always want to be in love with what I’m doing.”

Photo Assistant: Sam Pendlebury.