In his own words, Tariq Zaidi tells the story behind North Korea: The People’s Paradise – a rich, vivid and humanising portrait of life in the mysterious country

As one of the world’s most isolated countries, North Korea exerts a unique fascination in the Western imagination. It’s easy to misrepresent a place which is so secretive, and which has little opportunity to correct the record. Often the subject of lurid, outlandish and factually dubious reporting, North Korea is typically portrayed as a cult-like dystopia, its inhabitants rendered as a faceless and undifferentiated mass.

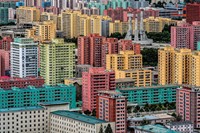

With his new book, North Korea: The People’s Paradise, Tariq Zaidi transcends these cliches and instead offers a rich, vivid and humane portrait. Shot between 2017 and 2018, the photographs span the diverse breadth of the country: from the austere, monumental capital city of Pyongyang to the lush verdancy of its mountainous regions; from military drills, rush hour commutes and manual labour, to people riding dodgems at an amusement park, fishing by the river and drinking beer at a barbeque. Even in these moments of joy and serenity, however, the presence of the state is never faraway. In one particularly resonant image, taken at a beach, a soldier in uniform stands in lonely vigil as women in brightly-coloured dresses stroll past along the shore.

Since beginning his career as a photographer in 2014, Zaidi has enjoyed international acclaim for his work, which documents social issues, systemic inequalities and cultural traditions around the world, often in communities which are in some way endangered or marginalised. Both his debut book, Sapeurs Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo, and its follow-up, Sin Salida (which explores human rights issues in El Salvador) won multiple awards. His work has been featured in a wide range of prestigious publications, including the Guardian, the New York Times, and the Washington Post, and has been exhibited around the world.

Below, Tariq Zaidi tells AnOther about the immense logistical challenges of working in North Korea, the welcome he received while there, and why he wanted to emphasise the vibrancy of everyday life.

“Many of my photographic projects deal with underreported communities and places. North Korea has intrigued me for years because of how little we know about it except from mainstream media. I wanted to use photography to offer a glimpse at everyday lives in North Korea, documenting people and culture as far as possible, given the limitations and restrictions of working there.

“For the past four years, North Korea has been inaccessible to all visitors, including North Koreans residing outside the country. Before this closure, access [for most nationalities] was possible through various agencies in China or Russia, which involved a process of applying for permission. During my visits, I was accompanied at all times by two North Korean minders, who played a crucial role in shaping the subjects I could capture. They frequently requested to view my images, leading to the immediate deletion of those they deemed unacceptable. Generally, they didn’t mind me taking photos of groups of people going about their daily lives, but individual portraits were discouraged. I had taken many pictures at an amusement park in Pyongyang at night, which were deleted – it was a very surreal environment to photograph, given the political situation in 2017 – and I wish I had been allowed to keep those. It’s hard to say what else I could have photographed because of how curated my first trip was; I didn’t have the chance to explore on my own. The places, routes, and destinations were all predetermined and could not be altered once set.

“Shooting in North Korea entailed several logistical restrictions, but I’m used to working in challenging and inflexible environments. Some projects I’ve worked on in the past have entailed significant safety restrictions because the context has been dangerous, politically volatile, or violent; others have had transport and mobility limitations where getting around the country and visiting points of interest has been impossible simply because of a lack of infrastructure.

“In North Korea, I never felt unsafe, nor was I met with any hostility as a foreign photographer – everyone I encountered was welcoming and hospitable. Children were generally OK with me taking pictures, and adults allowed me to photograph them after a few minutes of politely asking, although it depended on where we were. In the metro, for instance, whenever I pointed my camera at people, they all shyly put their heads down to avoid being photographed. I’m unsure if that was due to shyness or cultural differences. Like anywhere else in the world, I photographed those who were willing to be photographed and respected those who were not.

“Some of the photographs in the book capture a tension between regular life and the militarism, authoritarianism and control which have become associated with the country. I aimed to strike a balance by focusing on moments of leisure and community, while subtly incorporating elements that highlight the presence of broader societal forces. Through this approach, I hope to convey the resilience and vibrancy of everyday life, even amidst the backdrop of external influences or state intrusions, and invite viewers to reflect on the coexistence of ordinary experiences and socio-political realities.”

North Korea: The People’s Paradise by Tariq Zaidi is published by Kehrer Verlag, and is out now.