This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Drones and beats echo through Tate Modern’s vast Turbine Hall. Lights pulse in choreographic movement. From the ceiling, speakers and screens descend, synchronised. A film in which a ventriloquist intones a monologue is projected upon multiple screens; we hear her voice but her lips are unmoving. The film cuts between images of her and a cuttlefish – a liquid, morphing, flaring body. Is she ventriloquising through this cephalopod? Is it speaking to us? “The machine is animal” is one of the oblique phrases she utters.

This is just one sequence in Anywhen, a work made for Tate Modern by Philippe Parreno in 2016. It was a landmark moment for the Paris-based artist who was born in Oran, Algeria. Since his earliest endeavours in France in the 1990s, he has attempted to characterise the spaces in which he shows, to cast them as active presences. He has said he aims to treat the exhibition as a kind of organism. He has also used the term automaton – a machine that has a life of its own – to describe the way in which every aspect of the environment of the museum or gallery, from film projections to the blinds over the gallery’s windows, can be activated in his shows. Nothing appears fixed or static, even immediately outside the exhibition: Parreno has programmed snow to fall in front of gallery windows so that he transforms the landscape beyond. He makes his audience active participants rather than passive onlookers – often he installs sensors so that data gathered from our movements, or the heat we generate, informs the dramaturgy of his shows. In Anywhen, the scenario of the exhibition – including lights that rhythmically flashed along an arcing rod and the slow rise and descent of the screens – was triggered by the activity of yeast growing in an incubator in a room at the end of the Turbine Hall. The yeast’s behaviour was also controlled, connected to a weather station on the roof of the building – the data it captured, relating to the wind, light and heat outside, was transmitted to a bioreactor determining how the yeast was fed.

If this sounds impossibly futuristic, like something from nscience fiction, then it is quite deliberate. As Parreno has challenged the very form of art and exhibitions, he has had one eye on the realm of speculative fiction and imagined futures. He has been supported by a host of similarly future-focused collaborators, including Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Liam Gillick, and Pierre Huyghe, with whom he bought the copyright to a manga character called Annlee, which was then shared with a number of artists as part of a project called No Ghost Just a Shell (1999-2002).

These collaborations are always at the heart of his installations. In Echo2 at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris in 2022 – a show again informed by the bioreactor and made up of multiple moving parts, including a mobile sound wall and heliostatic mirrors that followed the Earth’s orbit around the sun – Parreno presented his film Anywhere Out of the World (2000), in which Annlee delivers a melancholic monologue about her fate. Having been bought for $400 by the artists, she was destined, as she put it, “to join any kind of story, but with no chance to survive any of them”. Near the screen was the artist Tino Sehgal’s choreographic work in which performers embodied Annlee and interacted with visitors.

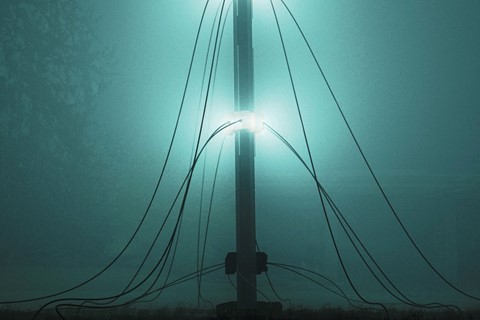

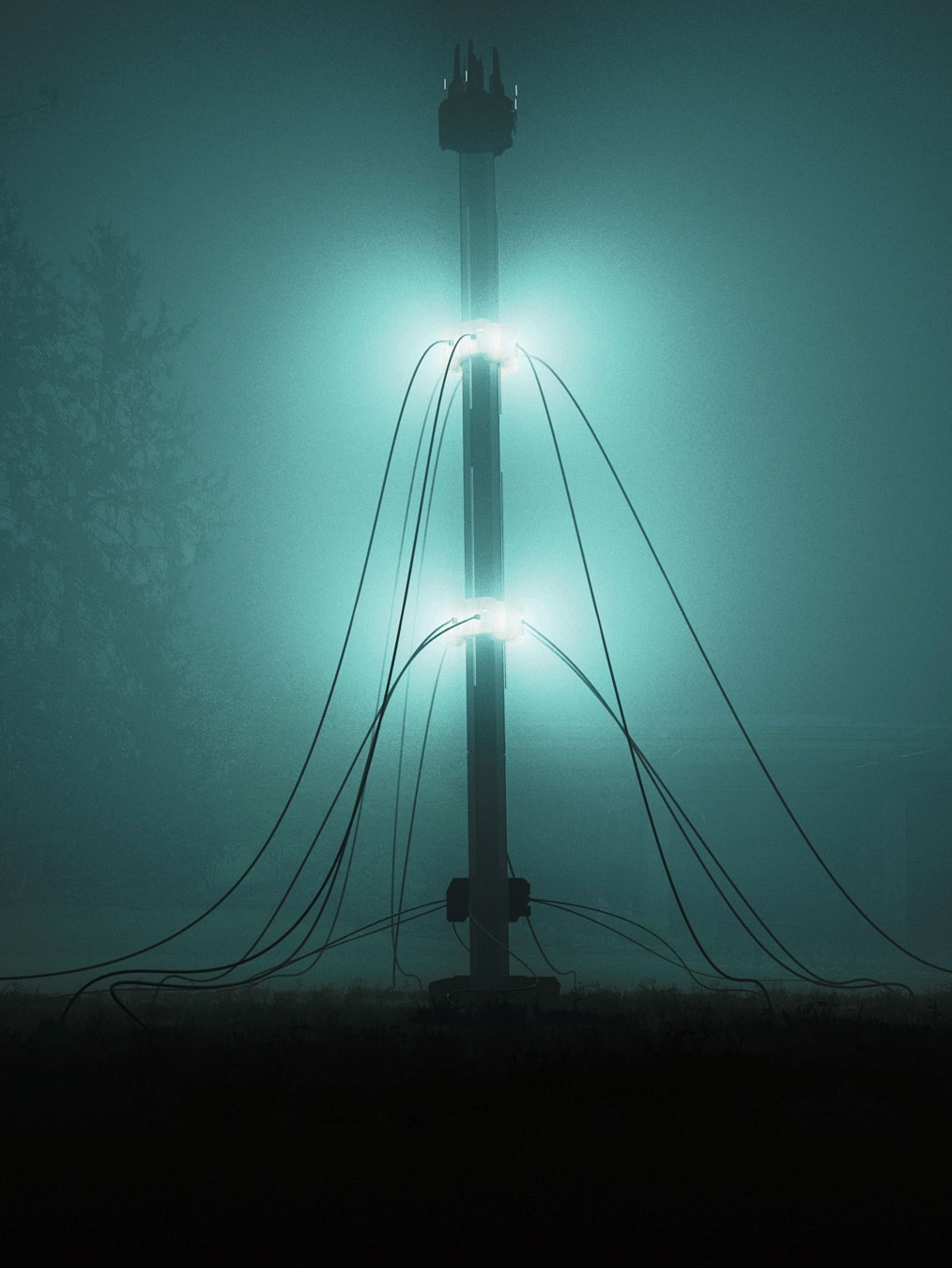

While the forms that Parreno’s work takes can vary hugely, they have a common concern with language and, increasingly, the idea of voices – those sonic elements, real or artificial, that have drifted through his exhibitions right from the start, when children chanted “No more reality!” in an early video. As he embarks on creating his first feature-length narrative film and plans ambitious exhibitions at Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, Basel’s Fondation Beyeler, Haus der Kunst in Munich and Pola Museum in Hakone, Japan, he reflects on how he is finding new ways to set the voices in his work free. Across the following pages are works from previous gallery shows (Parreno considers these his test sites for large-scale exhibitions) that will morph to suit their new surroundings. Alongside these are exclusive previews from behind the scenes of the construction of the new cybernetic Membrane sensor.

Ben Luke: You have a book about to come out called Voices: A Collection of Spoken Words, which features transcriptions of your films, sound pieces and performances. I love the idea that you are returning to the script from the finished work.

Philippe Parreno: When I started to talk to Haus der Kunst and the Leeum about a survey show, we thought about my work over the past few years and how there’s always an element of speaking. Think of the voice of Annlee or Marilyn Monroe, which was part of my Marilyn [2012] film, or even the cuttlefish in Anywhen – there is always something trying to speak to you. Even when [the Scottish artist] Douglas Gordon and I made Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait. Zidane’s voice was trying to be incarnated by the body. We experimented with his presence so that his breathing was all around the cinema and not in the centre of the screen, to see how we could desynchronise the body from the voice. This detail seems to recur in all my exhibitions – there has always been an acousmatic voice, a voice with no origin floating and trying to be incarnated.

In previous shows my use of sensors would bring the outside into the exhibition space – a film would start and stop and then you would hear a street sound from outside. By making the exhibition space transparent in relation to the world, those external events exist within the exhibition timeline. Now these forthcoming exhibitions, and the book, assume that these sensors do not serve the show but act as a kind of presence, a being. It’s a leap towards abstraction – these sensors are responsible for what they perceive and what they can do with those perceptions. None of the sensors I’ve used so far are camera-based or deal with vision. They are all occult sensors – considering things that are not visible to humans. They sense the tiniest changes in temperature, atmospheric pressure or shift in the magnetic field. I now have 42 of them. And all their data is correlated in this weird synthesiser – like an analogue modular synthesiser from the Seventies – and slowly creates some form of language that might be musical, like whale song. I will install a cybernetic structure, called Membrane, outside the Leeum, and with what it learns the structure will go to Beyeler and then to Hausder Kunst. After these shows it will start to form a language. So I am trying now to detach the sensors from the exhibition they are supposed to serve.

BL: The sensors were also present in Anywhen. I know they are triggered by external factors, or rather they provide the information that triggers a series of events. Once you have got that structure in place, to what extent can you personally tweak it to create events that are closer to what you hope for? Once it is in place, is it tweakable to an infinite degree?

PP: Yes, which is why I started to think they could make a brand new language. I chose sensors that would trigger data within the scope of human language, meaning 30 to 40 words a minute. I always need a frequency I can then correlate to some kind of presence so there is a match between the data and the way words are produced in time – words or other forms of non-human language, like proto or post-languages. From there we built it up slowly that way. At the beginning I thought we would have 30 to 40 different sensors, each one of them being a phoneme of this new language, but that didn’t work out. I would rather do something more musical, in a way – hence the metaphor of the synthesiser from the Seventies – an analogue language rather than making it a digital language.

BL: The wonderful thing about that analogy is that the capacity to modulate in those modular systems is quite radical and will provide you with all sorts of unexpected pleasures. To create systems for the unexpected is a core principle of yours.

PP: A system for the unexpected is definitely a good way to put it. I certainly find the invisible very interesting. A few days ago I went to see the Mark Rothko exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and last year I saw a Mondrian exhibition at Fondation Beyeler. I loved the way Mondrian started with figurative painting, then moved on to abstraction and went back to figuration. Abstraction is not the end. My desire to go away from the exhibition is also a way for me to go towards abstraction. I don’t look at a show as an opportunity to display pre-existing work that is figured but more to take it as something that can produce its own presence in time. This direction is far more interesting to me today. Maybe at some point I will go back to the classic form of exhibition and non-abstraction. But right now this is what I’d like to explore.

“I don’t look at a show as an opportunity to display pre-existing work that is figured but more to take it as something that can produce its own presence in time. This direction is far more interesting to me today” – Philippe Parreno

BL: I have always wondered about the motivation behind this choice. Was it that the museum was a good place to display art that was, in itself, a fertile ground, or was the idea of having these exhibitions as objects a means of challenging that space because it was inadequate for containing your ideas?

PP: Now, indeed, it is related to the museum space, but I was trained, and approached art in the first place, through art centres rather than museums. For me, art has always been a plateau where things could happen, and those things were not really meant to be collected. Back in the 1980s there were these large exhibitions that people like Lawrence Weiner and Daniel Buren were doing. It was not about objects but an idea of space and time with no beginning nor end, a place free from any spatial and temporal constraints. There was no narrative arc to it. It wasn’t a black box or a white box, but a place where things could happen, and you relied on the exhibitions before yours to guide you. It was a place where some form of knowledge could be produced. It was a space in parentheses, if you like. And I still think about it like that, in a way. To me, an exhibition is a momentum. Maybe there are objects that could be collected but that’s not really the point.

BL: You are also in the process of making a feature-length film called 100 Questions, 50 Lies (A Recital of True Events), and last summer you showed some drawings and paintings on paper at Pilar Corrias [in London] with the same name. Were those a storyboard for the film?

PP: Yes, I did a bunch of them. I drew storyboards for the films that I wanted to make – I did some drawings for the film Continuously Habitable Zones (CHZ) [2011] and others for Marilyn at the beginning, because it helps me to think about the film. And they became what they call in cinema a mood board. I also make them because if I don’t end up using them for a film, then at least I can always do a comic book. They act as a guide to show to Darius Khondi, the cinematographer I am working with, or the rest of the team, because with film you have a bunch of people you need to talk to. It’s a bit like a palette that I will show even to the actors so that they can feel the mood or the tone of the film.

BL: I know you have read a lot of science fiction and absorbed that genre through writers like Stanisław Lem. That language is inside you almost by osmosis – without having to consciously refer to anything in particular.

PP: It is speculative and it is definitely science-fictional. It is a projection. In technology and, specifically, in AI and machine learning, they use the word “epoch” to mean the time employed by a system to understand the data that passes through it. We say “This is one epoch” when you train a system and it has understood. I am interested in epochs but I am also interested in prediction. When you work on an exhibition it’s the same, it’s like you work on an epoch. But it is nice to see how one thing can lead to another and eventually produce something uncertain and unclear. Something science-fictional, predictive or prophetic, to throw something into a virtual future.

BL: You mentioned your project Membranes: An Anathema earlier, which you’ve described as a “cybernetic stage project”. What more can you tell us about that?

PP: That is the tower that I talked about before which will be in Seoul and then included in these shows that will slowly produce this language. If I make one or two of these towers, I would like them to be played by musicians – I look at them as a sensitive organ, just as with the modular synthesiser I mentioned before – if I continue to develop it in that direction. That is the next stage – first I need to link it to an exhibition process, but from then they are completely independent and start to become things in themselves that can be played, or fed instruments or musicians. So they become something that can feel and sense and [their findings] can be played.

BL: Your upcoming shows will inform each other and you have used the term “survey” to describe them. However, it seems that, for you, the idea of a traditional survey doesn’t apply. Take the Zidane film – I have seen it three times and its presentation was different every time. I have seen it cinematically, as an installation, and so on. So none of your works are ever actually finished.

PP: It is true. It is always incomplete and even if it is locked and technically complete I break it and do something new with it. Today most of my works have a digital file attached to them that can be altered or modified. I often compare my production to traditional ritual objects from Mali known as boliw, which are forms moulded for ceremonies. The idea is that, each time you see an object presented in a particular place, it has a certain shape and meaning and then the object goes away either because it is time for it to go somewhere else or because it needs to leave that site for something else to happen. Years later, if you were to bring that same object back, it would have a different shape as it has been altered over time. In Mali they are ‘fed’ with sacrificial and organic materials by the priests or elders and therefore tend to become oblong or roundish with entropy. So they grow each time they reappear. I believe it is the same with exhibitions. I am sure you have had the experience where you remember a painting you saw some time ago and then you see it again and it looks different, whether because you forgot it and you resee it, or reinvent it, and then when you refer to it in your imagination it has a different shape and form.

BL: That perspective also privileges the spectator’s role. Through the centuries it has almost become a tradition – it goes back to Duchamp. And that idea of privileging the role of the spectator is so endemic in your work. It is also part of the long history of the French art centres you were referring to before. The art world you entered in Grenoble was totally about the spectator having a much more direct engagement with the artworks than they would in a traditional museum. Is that the first thing to consider when putting on a survey show? What is the role of the spectator in this context?

PP: You have a space that is given. And that’s why the works change, because the space in which you experience the show also changes. It’s like a weird organism. If you have a group of fish and put them in a tank they will adapt and form a different type of ecology within the given milieu that they’re offered. And, in exhibitions, I alter the work to function better in the space that hosts it. To go back to Duchamp, there is this beautiful line he once wrote on foil candy wrappers that read “a guest plus a host equals a ghost”. You need these two terms to produce form – the ghost, which is the result of the encounter between a host and the attention of the public. These two terms produce a third one, which is what you see.

BL: And it is poetic because it speaks about the haunting that, again, permeates many of your works – things lurk. There are mechanisms whereby a film screen appears at a certain point, the works become actors – they pass through the exhibition as opposed to just permanently being there.

PP: Exactly. They morph and live differently within the new system, the new world they have found. And because you see one work next to another, they transform.

“If you have a group of fish and put them in a tank they will adapt and form a different type of ecology within the given milieu that they’re offered. In exhibitions, I alter the work to function better in the space that hosts it” – Philippe Parreno

BL: In your 2024 shows, you will exhibit in a loaded museum like Haus der Kunst, which was designed for Hitler. When you come to a place like that after more contemporary art centres like Seoul’s Leeum museum, does the haunting of that environment influence how you install the work? Do you think about its long history or hold it at bay?

PP: Not really, no. The Leeum museum is weird because it is the only museum in the world where you have three architecture projects, one next to the other, like a weird creature. The left hand side is Jean Nouvel’s, the right-hand side is by OMA, and the central one is Mario Botta’s. It is a concretion of three different architectural buildings fused together, it’s like the Surrealists’ cadavre exquis – an exquisite corpse. But does the work that I do comment on that? Not really, you just take it as a given. Of course you have specificity to it – all rooms are blind to each other, which is what led me to think that it could be the right place to talk about the occult. Things are happening, something is haunting this place because of what happened in its different spaces. The space in Haus der Kunst is quite like Palais de Tokyo in Paris – you see this kind of large space in Europe quite a lot, so it’s not that there’s a specificity to Munich and this fascistic legacy. You have them everywhere. But this one’s past has been commented on a lot. I take it in a similar way to how Haus der Kunst’s director, Andrea Lissoni, has taken it the work is part of a programme led by Andrea and I will arrive at a specific moment of this programme. The direction I will take there will be reminiscent of Duchamp’s Bachelor Machine – much more mechanical, much more abstract. I don’t even want to show any works in it. I am still just in the process of doing it, though, so we will see.

BL: I love the idea of it being a moment. You are like a comet passing through the museum.

PP: Exactly. I am always a guest – I arrive, I appear and then I disappear. I am like a ghost.

BL: You are indeed.

Philippe Parreno: Voices is at Leeum Museum of Art, Seoul, 26 February until 7 July, and at Haus der Kunst, Munich, 22 November until 20 April 2025; Sommerausstellung is at Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 19 May until 11 August; and Philippe Parreno is at Pola Museum, Hakone, Japan, 8 June until 1 December.

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally now. Order here.