A new exhibition in Berlin pairs the work of Jimmy DeSana and Paul P, two artists who pushed at the limits of photography and depicted queer desire in new and unconventional ways

The portrait is a form that always seems to be evolving. The trajectory from the centuries-old method of a model sitting for a painting, compared to the immediacy of being able to take out your phone and capture yourself with the push of a button, reveals so much about the intersection between technology and art. But some art engages with the portrait not just as if its form were a straight line, but instead something more malleable, that can force us to reconsider exactly what it is we’re looking at.

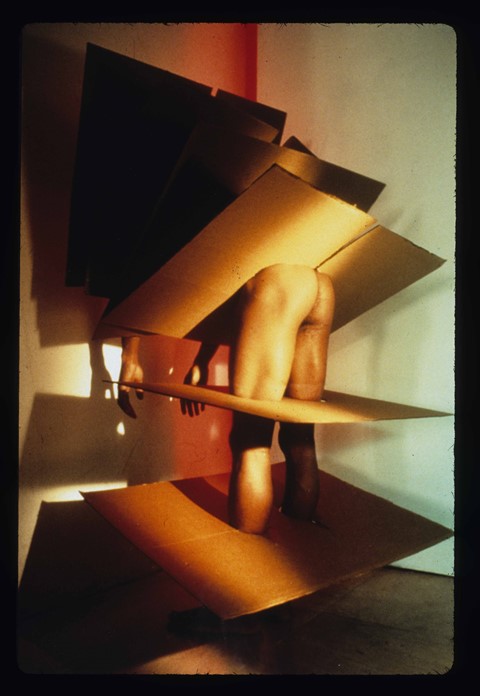

In Ruins of Rooms at KW Berlin, the work of photographers Jimmy DeSana and Paul P pushes at the limits of both what photography looks like, and the effect that these images can have. DeSana’s work became steadily more experimental throughout his life; the early black-and-white series 101 Nudes (1972) offered glimpses of DeSana’s friends nude in domestic environments. In stark contrast to this, his images from the 1980s like Cardboard (1985) and Ladder (1980) turn the body into something more abstract, fusing it with domestic objects.

DeSana’s work occupies a space between the intensity of eroticism and a surreal, detached objectivity; something he once stressed to his friend and collaborator Laurie Simmons, saying, “I attempted to use the body but without the eroticism that some photographers use frequently. I think I de-eroticised a lot of it.” This is no surprise; throughout the 80s, the Aids crisis began to cut through the United States, permanently changing the ways in which we might look at and understand the queer body. Eventually, DeSana himself would pass away from an Aids-related illness in 1990.

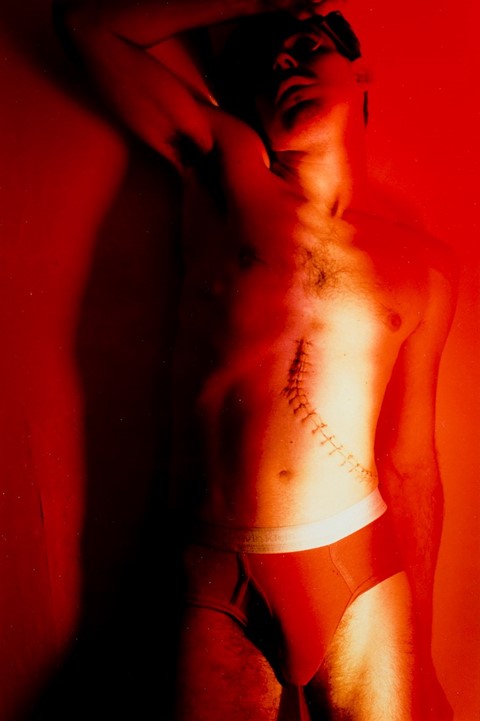

Paul P feels like a direct artistic descendant of DeSana’s in terms of the tension between sexual desire and objective voyeurism that informs his work, and the shadow cast by the Aids crisis. Paul P wrote in a text accompanying his solo exhibition Gamboling Green, “Having been born in 1977, my self-awareness developed in relative lockstep with the ravages of the Aids crisis. The position of coming-after obviates nostalgia.” There’s an almost unsettling stillness in Paul P’s paintings, his subjects caught between breaths and furtive glances, unsure of how to articulate their desires. In Untitled (2020), a figure lies down, eyes closed; they may be asleep or in the throes of some fantasy. Here, Paul P puts an emphasis on the same tension that DeSana does, asking the viewer to consider what kind of desire his images stir.

Paul P also engages directly with the idea of death and loss in the queer community; his work is often inspired by the LGBTQ+ archive from Toronto, placing these images from pre-Aids gay porn magazines into a more contemporary and much darker context. Coming from the time between Stonewall in 1969, and the dawn of the Aids crisis, Paul P’s archival work represents what the artist calls “a golden age.” This golden age though, can never be reclaimed; it’s no wonder that the subjects of Paul P’s images so often feel obscured, hidden from view; in Untitled (2021), we see only the back of someone’s head and their red sweater. But there’s something almost distorted about the back of this person’s head (at a glance, it looks like the poster for Pink Floyd’s film The Wall), and in Untitled (2020), a figure looks out at the viewer, face hidden by smoke.

Where Paul P’s subjects are hidden in the mists of time, DeSana’s are made abstract, with emphasis on anything other than the – often nude – bodies that his work displays. In Parka (1986), the eponymous object sways dramatically in the wind, drawing the eye much more than the otherwise naked body that it adorns, and Watermelon (1979) turns the erotic image into something absurd, disarming the expectations of any onlookers. It’s no surprise that Simmons said of DeSana that her “belief in the work has grown and grown and grown. It becomes more extraordinary all the time.” Taken together, the work of these artists becomes a testament not just to the transformative powers of photography, but of the archive, continuing to complicate the relationship between what we look at and what we see.

Ruins of Rooms by Jimmy DeSana and Paul P is on show at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin until 20 October 2024. Salvation by Jimmy DeSana is published by Primary Information, and is out now.