As a new exhibition on Alice Neel opens in LA at David Zwirner, critic and curator Hilton Als discusses the late artist’s remarkable humanism

In 1972 Lou Reed wrote Walk on the Wild Side. The song, which would become Reed’s most famous, paid homage to a group of Andy Warhol’s superstars. One of those stars was performer and playwright Jackie Curtis; of Jackie, who was genderqueer, Reed sings, “Jackie, she is just speeding away / She thought she was James Dean for a day / But then you know that she had to crash.”

Another artist immortalised Jackie that year – the inimitable painter Alice Neel. In Jackie Curtis as a Boy, Jackie plays James Dean, America’s forever boy. He looks out warily, his gaze vulnerable yet distant, brooding if not slightly petulant. “It’s an amazing example of how Neel is able to represent transmogrification, that you evolve and change,” says Hilton Als, who has curated a new exhibition of Neel’s work that features the painting. “She was amazing at that in a still medium.”

The exhibition, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, opens at David Zwirner’s Los Angeles location on September 7, and is the second exhibition on Neel curated by Als. The first, Alice Neel, Uptown, focused exclusively on Neel’s portraits of people of colour, highlighting an aspect of her work that had long been overlooked by curators. At Home similarly shines light on an underappreciated strain in Neel’s body of work: the queer artists, politicians, writers and activists she sat with and immortalised on canvas.

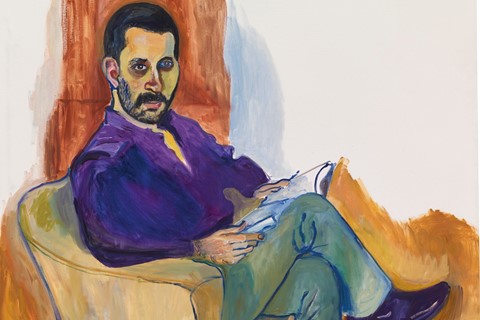

At Home chronicles decades of queer life in New York. The exhibition and companion catalogue feature Neel’s vibrant portraits of well-known figures like Warhol and the poets Frank O'Hara and Allen Ginsberg, as well as those who may have been lost to time if it weren't for Neel’s paintings of them, such as Vogue fashion editor Ron Kajiwara. “I love what she conveys about him, which is a self-containment born of several things, one being fashion,” elaborates Als. “He’s a fashion person, but he’s also an Asian person in a white world. There’s something so moving to me about that picture, which is a kind of pronouncement about style, but also about covering up. That took enormous sensitivity, for her to convey this covering up, the way in which we don’t reveal, in a portrait. That sometimes we are loath to share more vulnerability in a world that would attack us for being different.”

Noted for her remarkable ability to capture the inner spirit of her subjects, Neel has been called an “anarchist humanist” and a “collector of souls”; her paintings vibrate with vitality, with figures alive and wholly themselves. Born with an endless curiosity, she desired to know the world through the people who inhabited it. “Being born, I looked around the world and its people terrified and fascinated me,” she once said. Being around people brought her immense joy; she would miss them deeply once they left her apartment in the Upper West Side, where she painted for 22 years. “As an integrationist, I was so fascinated by her,” Als says. “It was so powerful to me to understand, in going through various aspects of her work, how broad her range was. As a humanist, I wanted to explore that.”

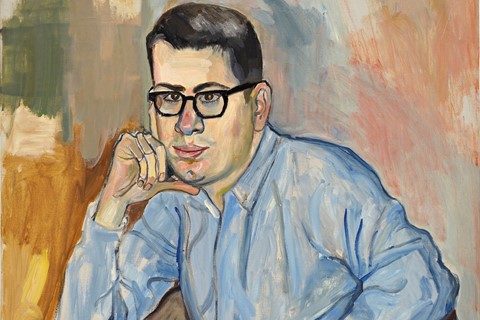

Despite Neel’s undeniable talent, the art world ignored her for the majority of her life. One of those people was the powerful curator Henry Geldzahler, who Neel painted in 1967 (Geldzahler was a curator of 20th-century art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from that year until 1978). He would go on to snub Neel, excluding her from his landmark exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-70. Perhaps he found her portrait of him too revealing, for Neel was a master of social critique. “He’s like a big, round baby,” says Als of the portrait. “She’s not a small-minded person, but she’s showing how people are small. I love her truth in that picture, the truth of who he was. A very spoiled boy.”

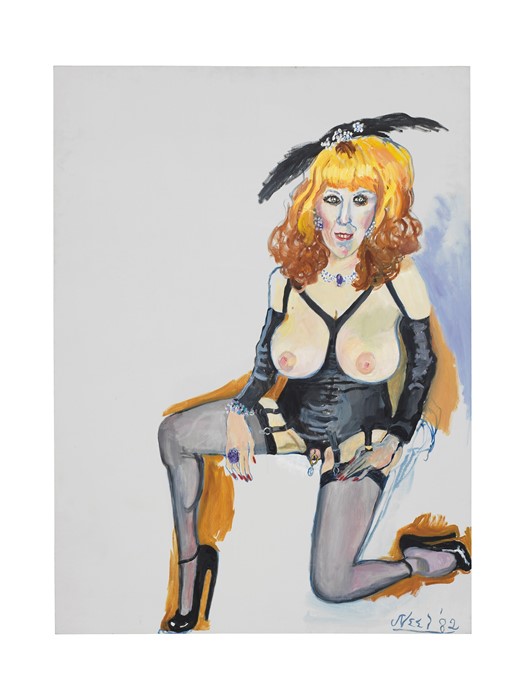

One of the most powerful portraits in At Home is Neel’s rendering of sexologist and performance artist Annie Sprinkle. It’s a remarkably sparse and focused painting, with all of Neel’s painterly energy focused on Sprinkle’s body. The leather outfit Sprinkle dons – leaving her breasts and labia bare, worn at Neel’s request – asserts her erotic freedom and dominance. It’s a painting about a woman accessing her vitality and life force. No wonder it was “a very sexy experience,” as Sprinkle once described.

Neel never failed to channel her own life force; painting with a miraculous fervour, the act of creating art fuelled her when despair threatened to take over. It took decades for painting to sustain her financially but it always sustained her soul. She remained enthralled by people, their strange ticks and habits and the way life left an imprint on their bodies and faces. To look at a painting by Neel is to witness that life force, a ghostly, wonderful feeling.

For Als, Neel’s work invites the “collective uncanny”, what we all “see and recognise emotionally without having language for. “One of the marvellous things about being a thinking adult is that we don’t always have the answers. Her work invites that. There’s a recognition of sameness and difference at the same time.”

“We’re living in an era where things can be over-explained,” adds Als. “But what if we weren’t? What if we confront something like a work of art by Alice Neel, where we really can’t explain why we get the shivers?” For a work by Neel undoes the boundaries of self we hold so dearly, returning us blissfully to our ephemeral bodies and selves.

At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World is on show at David Zwirner in Los Angeles until 2 November 2024.