The legendary surrealist filmmaker Jan Švankmajer is peerless – revered by animation legends such as Terry Gilliam and The Quay Brothers, his oeuvre over the last thirty years is without precedent or equal...

The legendary surrealist filmmaker Jan Švankmajer is peerless – revered by animation legends such as Terry Gilliam and The Quay Brothers, his oeuvre over the last 30 years is without precedent or equal. His early short films such as Down To The Cellar are haunting Kafka-esque investigations into imagination and the dark recesses of the human psyche shot through with pitch-black humour. These shorts arguably reached their zenith in his first feature Alice – his brilliant vision of Lewis Carroll’s tough child heroine, which suggested in no uncertain terms that the adult world is the natural enemy of the child. In later films such as Faust and Conspirators of Pleasure he took his ground-breaking stop-motion aesthetic even further towards a unique melding of live action and animation, as does his latest offering Surviving Life (something we all have to do). Sequencing real actors with two-dimensional hybrid cut outs reminiscent of Gilliam’s Monty Python years the film features a middle-aged man falling in love with a woman he meets in his dreams – a psychological by-product of familial childhood trauma. Although the film is lighter in feel than much of his previous work (look out for Jung and Freud battling it out Tom & Jerry-style in picture frames), it ploughs the same psychoanalytical furrow and confirms him as the undisputed leading light of contemporary surrealism. In this rare interview, he tells AnOther why human relationships have been commodified, virtual reality is an emotionally bereft landscape, and art is the ultimate tool for liberation.

Why did you want to explore the language of dreams, buried memories and psychoanalysis so expressly in Surviving Life?

I am unable to assess whether psychoanalysis works as a type of therapy. I have never been to a psychoanalyst. For me, psychoanalysis is, most of all, an amazing system for the interpretation of man and the world that works with traditional symbols – therefore, I consider it trustworthy.

More than any other director I can think of, you tap into something very dreamlike in your work – is it your intention to remove people from the everyday perception of the world?

In my latest film, I quote Lichtenberg as well as Novalis, both of whom say that it is dream and reality that together create a human life. This should apply all the more to art. After all, dream is one of the essential sources of imaginative creative work. And, I do not care for any other work. Creative work is a certain form of auto-therapy for me. Thus I liberate myself from the demons that moved in with me at some time during my childhood. If art has any sense at all, it lies in liberating man from domestication by civilisation and for it to be able to liberate the audience, then it must, first of all, liberate its creator.

"For me, creating hybrid creatures is a free game of the imagination. In fact, it is playing at god"

Surviving Life is very funny in places. Did you have a desire to make a more humorous film than some of your previous work?

I do not think along those lines. I realise ideas as they come to me and they themselves ask for the means of their realisation. The fact that it seems that this film works with less black humour than some of my other films has nothing to do with my own will.

Where does your desire to communicate come from?

My work derives from other motives than the desire to communicate. I have never treated film as a means of communication above any other. In the same unrelenting way, I put collages together, assemble objects, make graphics, ceramics or I engage myself in tactile experimentation. The surrealists say that there is only one poetry and it does not matter which means we use to capture it.

Surviving Life would seem to suggest we are products of our early experiences, some of which we barely remember - are we just the shadows cast on the wall by what has happened to us?

Plato has never been my philosopher. His ‘chase the poets out of the city’ has always sounded too totalitarian to me. Nevertheless, I agree with you and Sigmund Freud that we are the products of our early experiences. I certainly am.

What do you personally believe dreams are?

Freud says that dreams fulfill our most secret wishes. I could perhaps agree with that. But what definitely happens to me is that when my demons do not haunt me, I do not have dreams. But also my creative works steals my dreams. There was one dream that would obsessively recur in my childhood ‘The Dream About Foreign Soldiers’. And, yes, I used this story from my childhood in my film.

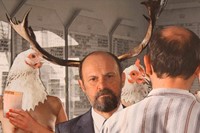

There is something Max Ernst-like about the people with the chicken heads in the film – why do you think we as a species are fascinated by hybrids?

For me, creating hybrid creatures is a free game of the imagination. In fact, it is playing at god.

What ultimately would you say is the role of the artist in society?

The Czech surrealist painter, Jindrich Styrsky, wrote that an artist belongs in the pillory. To that, I would only like to add that if the only sense of art is to liberate, then a poet must not accept any role in society, in order to maintain his independence.

Which artists have been most inspirational for you – why do you think surrealism arguably remains the most popular art movement?

There is a long list of gurus. Here are a few at least: Arcimboldo, the already mentioned Max Ernst, Magritte, the so-called Accursed Poets, the authors of the English Gothic Novel, the German Romantics, Lewis Carroll, Breton and other surrealists, Bunuel, Fellini, David Lynch and others. I certainly would not label surrealism as the most popular art movement. ‘It does not deserve it’. For that matter, ask any art historian and they will tell you that surrealism has been dead for at least seventy years. The fact that surrealism is still capable of attracting a certain group of young people is caused by its not being art but an alternative imaginative attitude to life and the world.

Why do you still choose to meld animation and live-action? What do you think about the trend in modern cinema towards CGI?

Means of expression and techniques – similar to an idea – cannot be the reason for creative work. Experience, obsession or desire must always be the reason. Computer animation is a technique like all the others. It depends on what we use it for. I do not use it for I have particular objections to it. In my view, it is lacking the tactile dimension. Virtual reality is the ‘not-being-touched’ reality i.e. ‘emotionally uncharged’ reality.

Looking back to your first feature Alice, there is a sense of isolation that carries through even into this work – do you think ultimately we are all alone?

Unfortunately, this selfish civilisation, adoring the utmost individualism, is becoming that way. Any solidarity is pejoratively labelled as ‘redistribution’. Everything is perceived according to its exchange value, including human relationships.

Surviving Life opens in the UK on Friday December 2, at the ICA London and key cities.

Text by John-Paul Pryor