Carson Stachura’s Palm Prize-winning series My Body is a Weapon (Waiting At Your Door) captures the realities of trans experience by placing agency in the hands of their subjects

There’s something otherworldly to Clem (As You Are), the photograph by Carson Stachura that won the judges’ panel special mention for the 2024 Palm Prize. In it, the eponymous subject stands, lit by theatrical lighting in a white shirt, cigarette in hand, and a pair of angel wings. According to Stachura, this image was born from a spontaneous shoot after the photographer remembered they had angel wings in their closet. Inspired by the Brooklyn drag scene, where people “take their existing look and fuck with it, and think of gender expression in a very dragged up way,” the photographer describes their practice as being deeply collaborative. “Conveying the experience of my subject is really crucial,” they explain.

But while both their Palm Prize-winning photograph, and their series My Body Is a Weapon (Waiting at Your Door) explore ideas around gender presentation, they also challenge one of the most hotly contested ideas in contemporary queer culture: the trans archive, what it can hold, and the purpose that it can serve. From its genesis, Strachura’s series challenged the idea of how we might think of an archive; they reveal that My Body Is a Weapon came about while exploring the idea of “the archive as a site of violence and photography’s role in maintaining that.” For Strachura, this is rooted in ideas around the “trans portrait” in the work of sexology clinics, and the “post-transition glamour shots” in the Digital Trans Archive. The more time they spent diving into this archive, the more the idea became clear that “trans people experience the violence of being looked at without consent”.

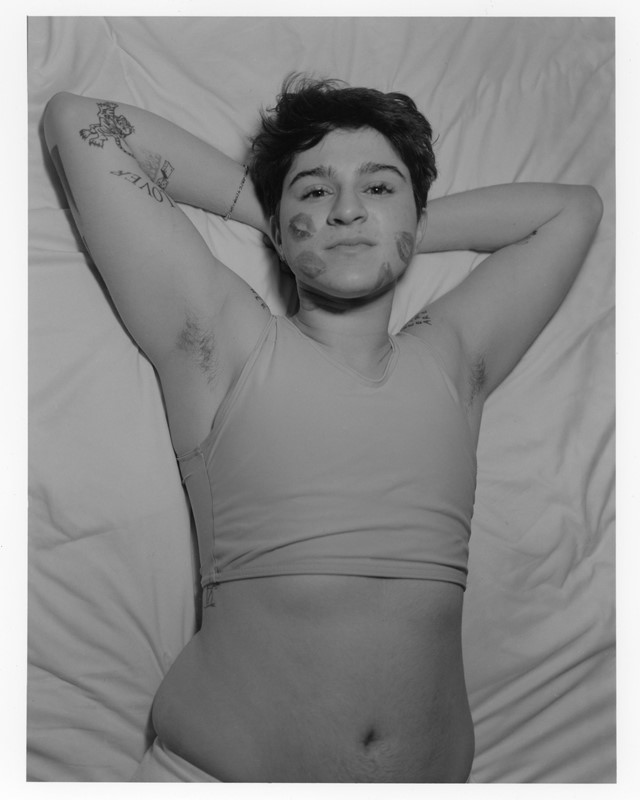

Throughout their practice, Stachura aims to reorient this idea; in images like their self-portraits from the spring and summer of 2023, to the intimate embrace of Eliana and Claire (Long Distance Lovers), their images capture the realities of trans experience in a way that places agency in the hands of their subjects, a stark simplicity that so often is missing from our understanding of trans imagery. By capturing solitary moments rather than narratives of transition – Stachura says that “clinical view of transness as having a distinct beginning or end doesn’t resonate at all with me” – their series is able to focus on “gender fuckery in myself and my chosen family”.

The idea of chosen family – something well known in queer circles, whether as a trope in so much of popular culture, or a way of understanding our own communities – is at the heart of the series My Body Is a Weapon, images that were shot “during my last semester of undergrad with an understanding of how that moment in time was fleeting. For a lot of us, it marked a period where we began articulating what we desired our bodies to be, as well as our relationships with each other,” says Stachura. There’s a comfort and ease to photos like Ezra, pre-op which reveal the intimacy of these relationships, and seem to capture Stachura’s hopes “not to participate as a voyeur”.

Alongside these portraits of chosen family, My Body Is a Weapon has a sly, if-you-know-you-know sense of humour embedded within it, from still lifes adorned with bananas, syringes, pills, and packers, to Untitled, a cracked egg presented without comment. Stachura hopes that their work will cause “viewers, trans people included, to think deeply about how they engage with trans history and what becomes illegible, not understood nor recognised, within these records”. They stress the fact that this work alone isn’t the only thing “redressing historical harm and archival violence”, emphasising how their photographs showcase just one of the many ways in which we might understand trans lives and communities.

But it’s this focus on specific experiences and groups of people that gives the work is power, and which allows us to reconsider the role the archive plays in how we understand ourselves. In describing their process, it becomes clear that Stachura’s photos are propelled by the impulse to let their subjects see themselves, in whatever form that might take, informed by conversations that they have with subjects before any pictures are taken. Their hope is that the gender-fuckery and flamboyance of their images feel like “a still-resonant extension of the subject themself, and for the subject to ultimate feel and be affirmed”. It’s in this drive towards affirmation, and the desire to zero in on the details and intimacies of specific trans lives, as opposed to trying to speak to and for a capital-c Community, that My Body is a Weapon reveals the many ways in which we can embody and imagine trans experiences; that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in a single archive.

The Palm* Photo Prize Exhibition is on show at 10 14 Gallery in London until 3 October 2024.