Challenging assumptions made of China from the outside, Amanda Ba’s new exhibition Developing Desire asks, “In this moment, what do Chinese people actually desire?”

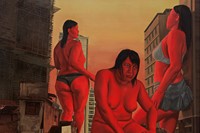

A gargantuan figure sits amongst a mound of rubble. She is dressed in sturdy knee pads with a giant barbell propped behind her back. In the background, semi-bulldozed buildings are scattered against a toxic orange and yellow sky. Even further in the distance are the hazy silhouettes of city high rises. Amanda Ba’s painting Rubble Titan is currently on show in Developing Desire, her solo exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch in New York. It is one of several works situating larger-than-life women in the midst of cityscapes and demolitions.

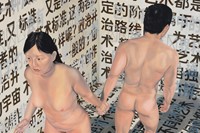

Heart Wall, a large painting installation that looms over the exhibition, is akin to a billboard. It presents 16 faces in close-up, their placement evoking the neat tiles of group Zoom calls. Each rectangle shows a woman dressed for a different activity; one has a swimming cap and goggles on her head, as though she is about to jump into a pool; another is decked out in official military uniform; a further figure wears a string of pearls and a bridal veil. The exhibition also features a three-channel video, mirroring the multiple screens suggested by the painting.

“I typically think of my solo shows as contained theses,” says Ba, who was born and is based in the US, but lived in China until the age of five and regularly visited through her childhood. “I knew I wanted this show to be about China. I hadn’t been back for four years because of Covid, which is the longest I’ve ever gone. I wanted to see for myself what post-Covid contemporary China is like. I also wanted to try to be my own person. When you’re young, those visits are so connected with family. It becomes more of a nostalgic or sentimental experience, which isn’t what China is about.”

The exhibition challenges assumptions made of China from the outside. Ba reflects on the popularity of family-focused film narratives, China’s economic battle with the States, and the one-child policy as cliches perpetuated by the West. “I don’t need to affirm or reiterate what people already think,” she says. Instead, the artist addresses the notion of desire. “In this moment, what do Chinese people actually desire? How does individual desire exhibit itself on a collective or national level?”

The video installation More Future Tryptic combines historical moments, contemporary footage, and thoughts on Buddhism and philosophy. It also explores, through narration, the psychoanalytic approach to desire. For this, the artist researched French philosophers who tried to reconcile Freudian psychoanalysis with Marxism, exploring how we function as part of an economy. Sigmund Freud saw desire as a central core within the psyche, but Ba is particularly interested in Jacques Lacan’s idea that it is bound up with the collective, driven by structures that we are born into. The exhibition plays with Lacan’s notion that desire is doomed to remain unfulfilled.

“The Lacanian idea of desire is that it’s constantly frustrated,” she tells me. “You have this feeling inside, but you can’t ever fully transcribe it into reality. You find things that are good substitutes, but when you get them, you realise they are false, and the desire is rekindled.” In the exhibition, Ba also delves into the drive to build and buy property. She understands this materialising in China’s swift development – Hefei, the city of her childhood, was at one point the fastest growing in the world. It is as though the desire to buy and inhabit new property is never fulfilled, as old sites are torn down and replaced with new builds. Ba compares the country’s recent housing boom with 1950s America, though she is intrigued by the paradox of this desire existing “under a so-called communist government” which outlaws land ownership.

This body of work reflects upon the desire to build generational wealth, and she notes a tradition for parents to buy property for their young adult children in anticipation of future marriages. “All sorts of desires are bound up with buying property,” she says. “It’s connected with the institution of marriage, and also ancestry, children, sex, ego, and career.” In 2021, one of China’s leading property developers Evergrande Group collapsed, generating a real estate crisis. She sees this being evocative of the frustrated cyclical nature of desire.

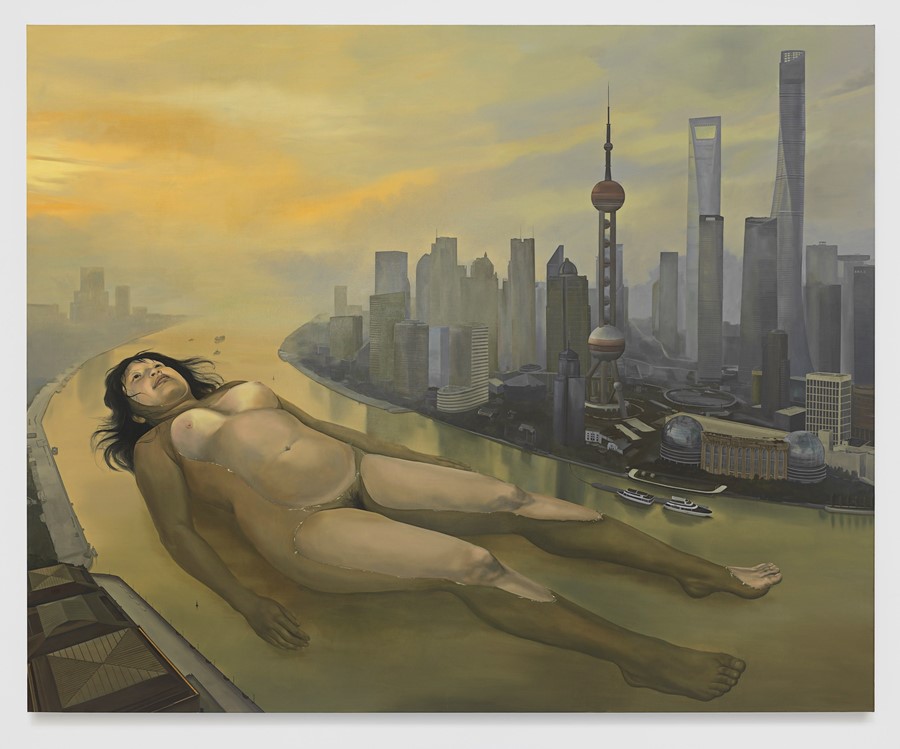

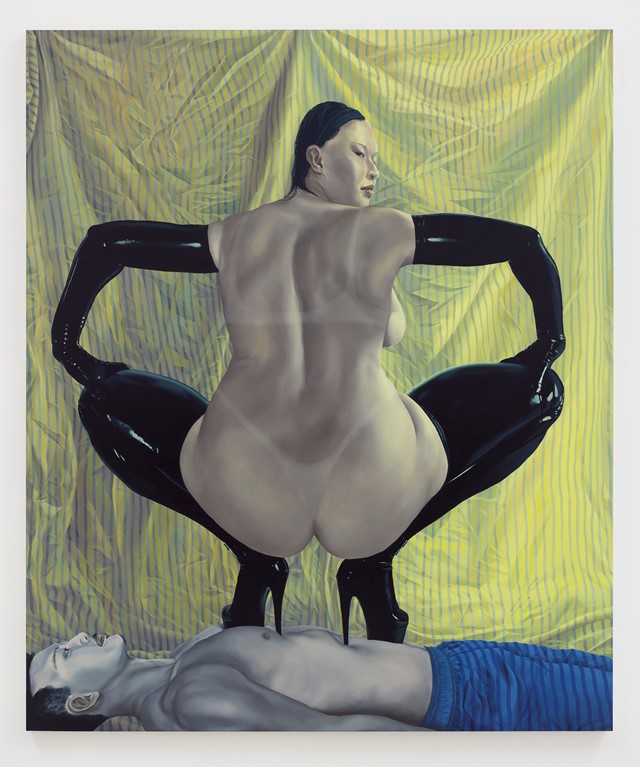

The giant human figures that dominate her landscapes are a frequent presence, though for this exhibition, she labels them as titans (rather than their previous definition, as “giantesses”). “Giantess is kind of kinky. Titan has a more monolithic meaning, which I thought was appropriate for this show,” she says. “I sometimes have questions about these giant Asian American nude women and what I’m trying to say with them. At this point, not very much! It’s not shocking or transgressive anymore. They are like permanent occupants of whatever world I’m exploring. Now, formally and conceptually, I’m much more interested in the environment.”

Ultimately, Ba is not looking to find an objective reality of China in her work, but to offer a different way in. “I never want it to be easy for the viewer,” she considers. “I am talking about such a complex subject, as an artist who isn’t living in China. I don’t want to overstep and be prescriptive or give myself authority in a role I’m still figuring out. I want to present my observations and research in a way that is open-ended. I want to make the audience feel uncomfortable in a way where they want to know more.”

Developing Desire by Amanda Ba is on show at Jeffrey Deitch in New York until 26 October 2024.