During the Covid-19 pandemic Senegalese model and photographer Malick Bodian – who photographed Naomi Campbell for Harper’s Bazaar and was featured in The Business of Fashion’s 500 Class of 2024 list – came to the realisation that he didn’t know his own country and continent as well as he’d like. “I told myself, you know what? Life is so precious,” says Bodian. “I should start doing things that I love to do. I would love to know more [about] where I come from. I promised [myself] I would go home more often.” Bodian used to visit Senegal every two years. Now, he goes every month or two.

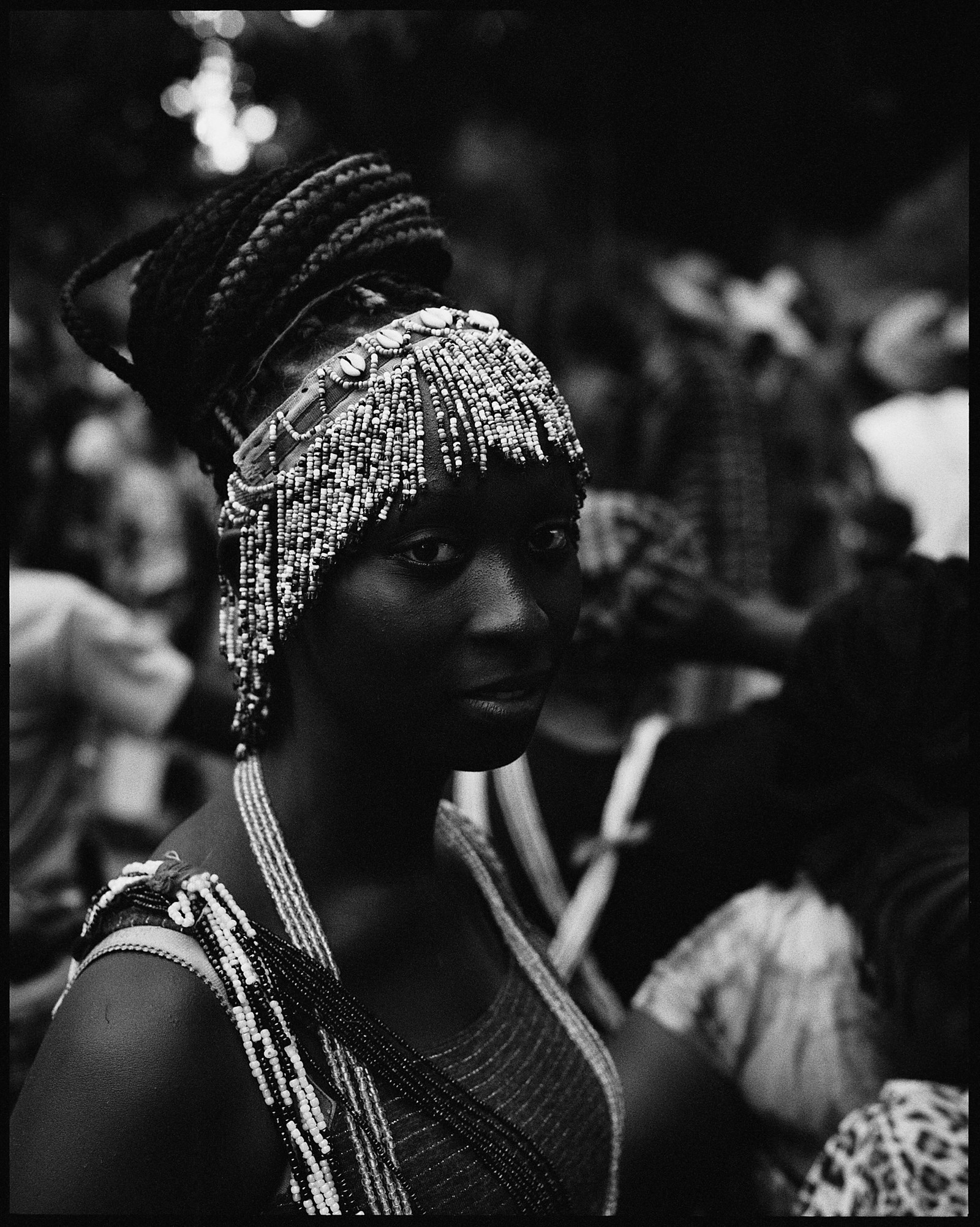

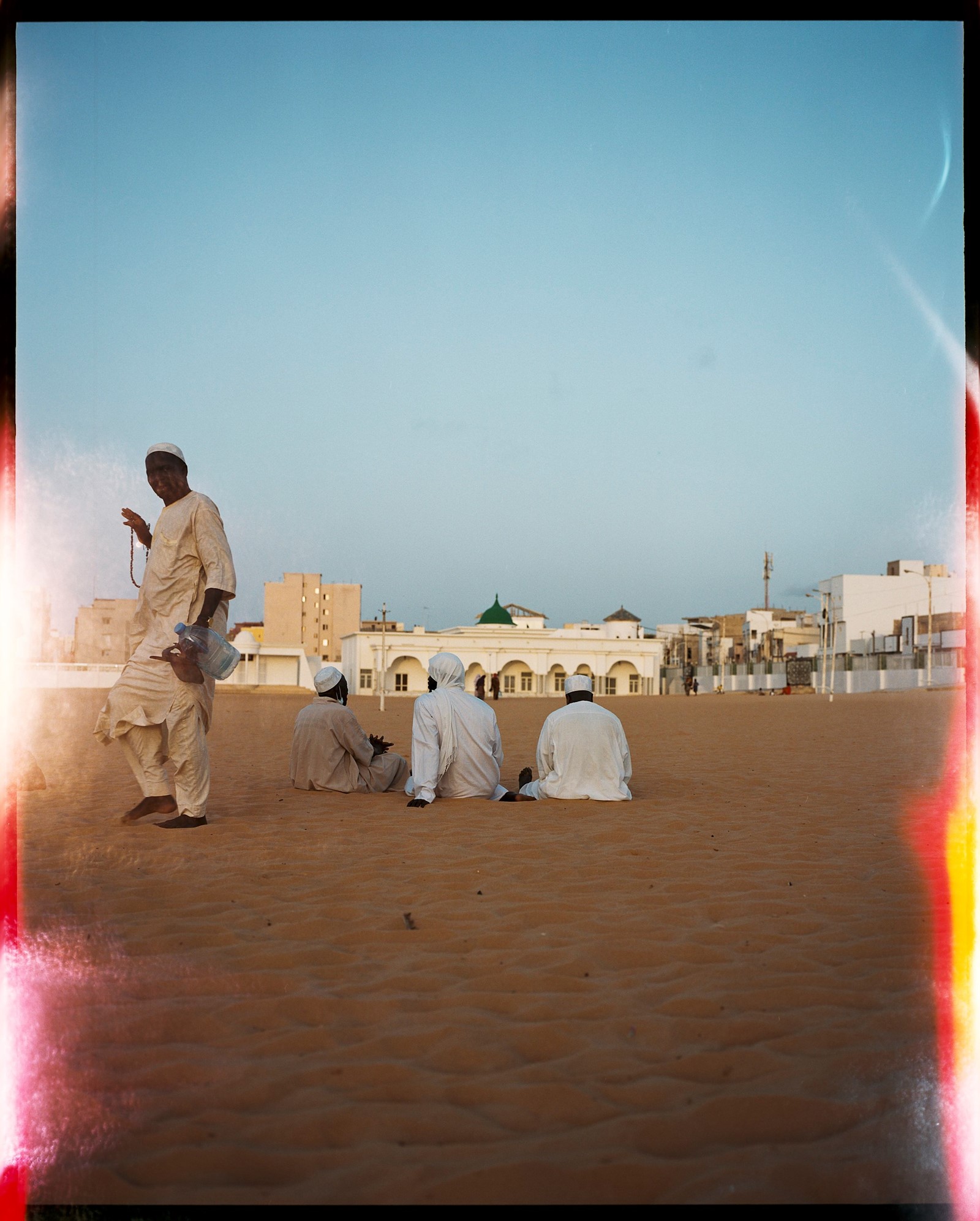

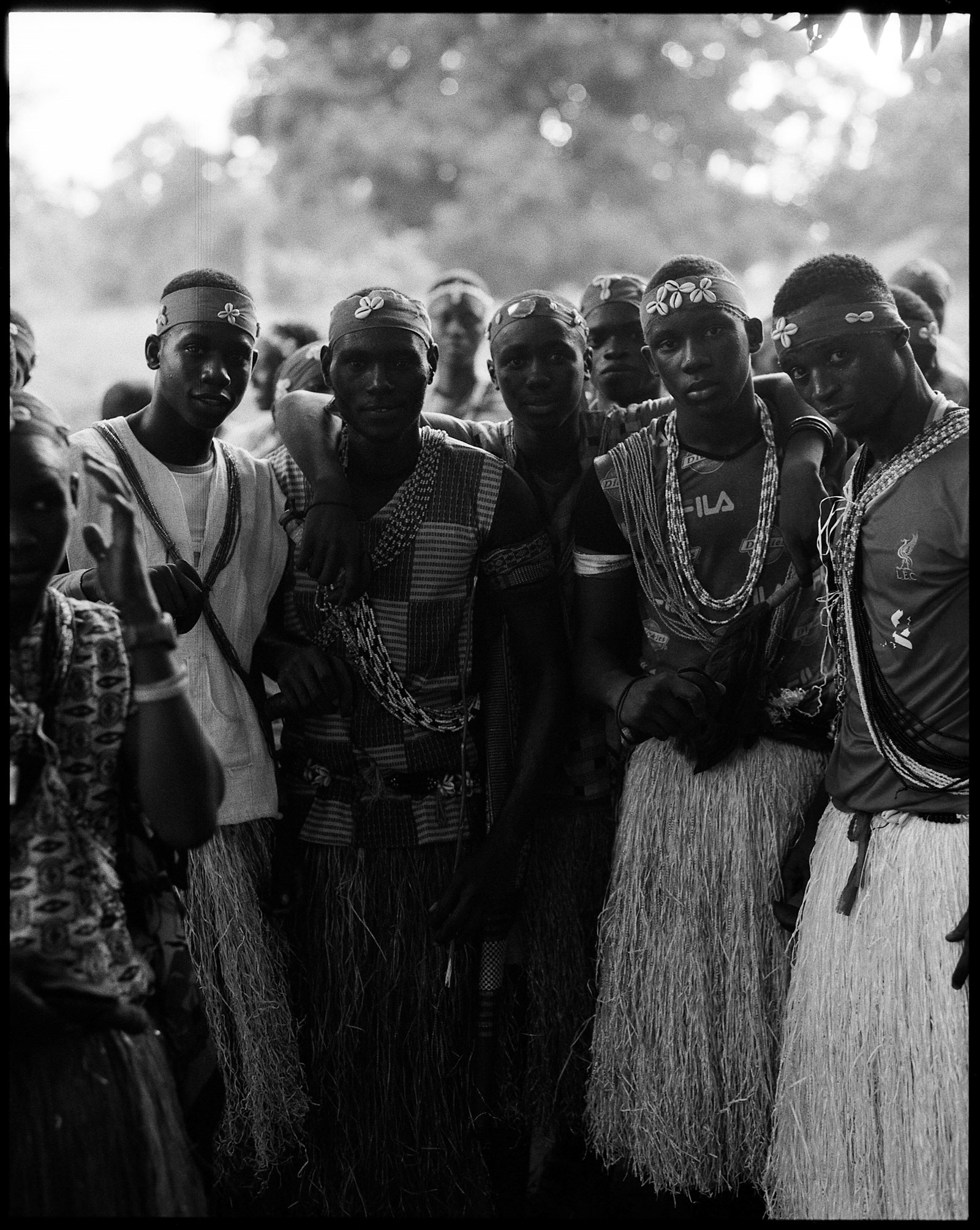

AnOther spoke with Bodian as he prepared for an exhibition of his first monograph Sénégal, Voyage Temporel, which translates to Senegal, Time Travel. Art directed by Simon B Mørch and Scenery, the publication documents the four years Bodian spent traversing the country. Bodian carried two Rolliflex cameras around his neck: one that shot in black and white and one in colour, a habit he picked up from fashion photography.

Sénégal, Voyage Temporel, is a graceful rumination on family, tradition and the passage of time. Bodian’s favourite photographers include the titans of 1970s West African studio portraiture such as James Barnor as well as Magnum photographers – Raymond Depardon in particular. His own work is like tagging along on a road trip; he takes us all around his country of origin, stopping to catch a glimmer of beauty here, a moment of synchronicity there.

Below, in his own words, Malick Bodian tells us more about the making of Sénégal, Voyage Temporel, why he prefers to work in film rather than digital, and more.

“I didn’t know my dad very well. The first thing I did was to go visit my dad, which is something I didn’t do for a long time. When I went to see him I met his mother, my grandmother, and she was 107 years old. I told myself, ‘It can't be a coincidence.’ That meeting inspired me to meet more of my family and explore my country. Sometimes when you live in a place you just don’t bother to visit it or to get to know it.

“At the beginning of the book, there are a few photographs of a ceremony. This ceremony is about my family. It was the second time I went to visit my dad. They have this ceremony that happens every 30 years and I was there two days before the training for the ceremony. It’s a ceremony that everyone from my family has to do. I spent time documenting the training for the ceremony. It was a very special moment.

“[When] I went through all the photos four years later, I didn’t know what to do. I knew that I wanted to make a book, but I didn’t know what book. What was the story? I started putting pictures together. Then I couldn’t see the black and white pictures and the colour together. So I separated them. I realised in the black and white photos there was something about the past [being] still present in Senegal, for example in tradition. For example, there is this family called Bétic, who ran away from Mali. They live [on] the border of Senegal and live like in ancient times. They have no phones.

“I realised that my black and white photos were all about [tradition]. It was not intentional. It’s basically what my eyes were attracted to. Every time I took a black and white photo, it was [of] something old, like an old building or old car.

“I don’t like to edit my photos. I like how the film looks naturally. I don’t like retouching. I want the photos to go straight to the exhibition and you see things as I saw it. This is the main reason why I like film.

“The title is about me travelling to Senegal. When [you] look at the photos I want [you] to travel in time without knowing which time they are in. In most of photos you really can’t tell. When did I take them? There are some photos in black and white [that] could be from [the] 2000s, some from the 90s, some from ten years ago.

“What’s interesting about a photograph is that it’s like time travelling. The second that you photograph it can never be like that [again]. Even if you photograph it a few seconds later.”

If you’d like to purchase a copy of Sénégal, Voyage Temporel by Malick Bodian, please enquire here.