Now on show in New York, Araki’s provocative series from the early 2000s captures “Kinbaku-bi” – the traditional art of erotic bondage

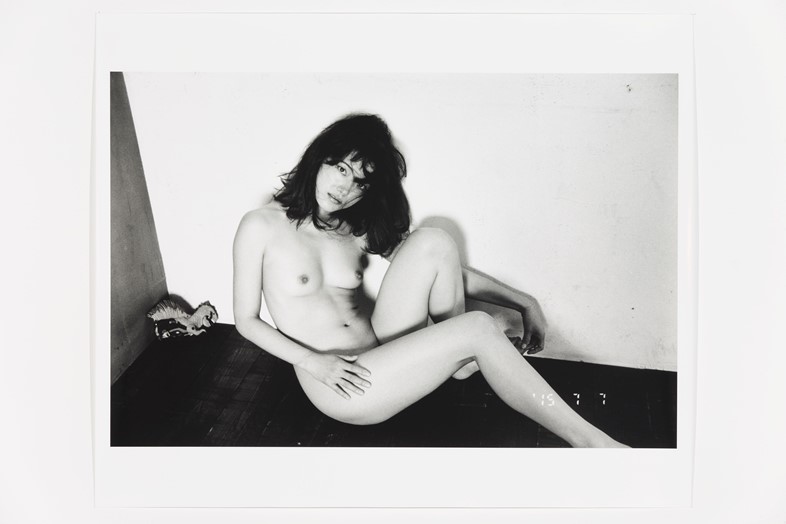

Nobuyoshi Araki is among the enigmatic contemporary photographers whose work – despite its suggestive sexuality – radiates a willful mystery and an insinuated invitation. Mostly shot in black and white, his images depict female subjects in intimate settings, often in strong dialogues with the camera, which posits itself in cinematic angles. The Japanese photographer’s images of Kinbaku-bi constitute perhaps his most well-known oeuvre in the West, lifting the curtain on his nation’s controversial and commonly misunderstood erotic bondage tradition.

In the photos, female models – hermetically tied with ropes – perform physically challenging contortions almost effortlessly. They inhabit casually decorated interiors with a few pieces of furniture. Washed by soft but determined light, their bodies are a site of combat between autonomy and submission. “An effortless sense of performance is played both by the model and the artist,” says Christoph Gerozissis, senior director of Anton Kern Gallery in New York, which has collaborated with Meredith Rosen Gallery for the new exhibition, Les Miserables.

The Upper East Side gallery’s presentation is a rare solo American outing of the 84-year-old artist’s oeuvre, which explores cerebral emancipation, not strictly through carnality and eroticism but by way of demise and reflection as well. “The question is not what the influence of certain things were on Araki’s life,” adds Gerozissis, “but the exact opposite: there is no separation because the camera is always present!” From documenting his wife’s slow death to shooting Lady Gaga or Björk and collaborating with fashion houses like Bottega Veneta, the artist’s photographs consolidate their subjects’ introspective energies.

Araki created the show’s silver gelatin prints in the early 2000s in the internet’s infancy before it changed our relationship to images – especially those with explicit sexuality – forever. Secrecy, kink, and desire are entangled notions in the modestly scaled stills, which reveal the details behind the Kinbaku-bi ritual. They refuse immediate codes of seduction while putting forth a contemplative veil before the models’ generously bare bodies. “Just take a look at other photographers’ images of Kinbaku and you will instantly see the difference. Araki is far superior,” Gerozissis notes. He explains the artist’s shots as “straight-on, not embellished, yet well composed in a ritualistic and performative sense.”

The models’ gazes are a crucial tool for claiming their own sovereignty. Often in a locked conversation with the audience through their eyes, the women gently claim their footings in Araki’s lens. The double-edged reality of sexually charged female nudity lensed by a man is filtered, in Araki’s case, through his approach to photography as his life’s grand project that seeps into rituals of mundanity as well as sexuality. Therefore, Gerozissis compels the viewers to take notice of what he calls Araki’s “hunger to document his life, every aspect of it, from love and death to the red light district, a taxi ride through Tokyo, to the clouds in the sky.”

Les Miserables by Nobuyoshi Araki is on show at Meredith Rosen Gallery in New York until January 18.