Vladimir Ovchinnikov is a veteran of the Soviet era and a key figure in the nonconformist movement, which rebelled against the state aesthetic of Socialist Realism, most notably with the ill fated but hugely significant Exhibition of the Workmen

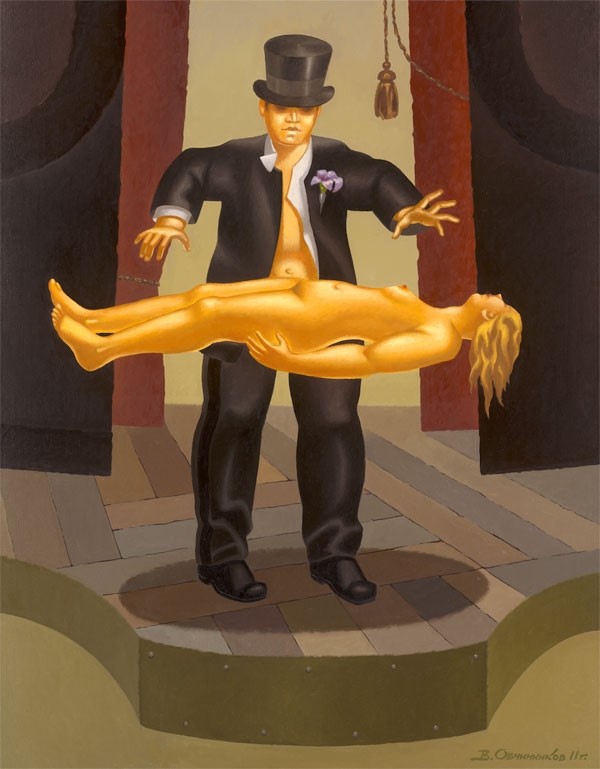

Vladimir Ovchinnikov is a veteran of the Soviet era and a key figure in the nonconformist movement, which rebelled against the state aesthetic of Socialist Realism, most notably with the ill fated but hugely significant Exhibition of the Workmen Artists in 1964 – shut down by the KGB after just three days. His latest works take their cues from religious and literary sources, such as Swift’s still bitingly vicious satire Gulliver’s Travels, and although he does not cite his countryman Mikhail Bulgakov as an influence, his paintings are arguably the visual equivalent of the literary master of magical realism – employing myth and magic to create a surreal universe of bulbous yellow-skinned people, one that often serves as a critique of hypocritical political and social conventions. Here, the legendary painter tells AnOther why he prefers incremental change to revolutionary fervor and how the Christian myth has become an all-encompassing mystical entity.

How has your practice changed in recent years, and what makes you want to reflect upon the act of painting in your recent work?

My practice is changing continuously, but it happens rather slowly. Like many things in my life, it needs a preliminary accumulation, step-by-step, and then "click" , something has really changed. Quick, principal or revolutionary changes are not for me, Lord save me, I don’t want them. Sometimes I am not satisfied with my paintings; I don’t exhibit them and I destroy them. It’s a pity I don’t have a fireplace for burning – it would be easier then. (Laughs) I don’t want to say anything with my work, just the same thing I say while talking to my friends and other people – that I do exist and I have my viewpoint on various things I am trying to reveal to my observer.

What would you say you have learned about the human condition over the years?

You see, if I only could tell… if I was able… I agree with the question because I am really learning. It may sound quite pathetic – I have insights from time to time but if I could clearly explain it in words I would not practice painting. Therefore all my discoveries, innovations and opinions are in them.

"There was only one thing to fight for – an artist’s right to have their observation"

To what degree was your practice and sensibility shaped by the censorship of the Soviet authorities?

I had to fight, but not with my creativity. I never fought either for or against anything with my painting. I did what I wanted to do. There was only one thing to fight for – an artist’s right to have their observation. This fight was real and we could barely win it. Although, in the 1970s even the most callous people realised the system wouldn’t last for much longer because of its rottenness and instability. Then it all started to change and the first exhibitions emerged. If you were an artist or considered yourself to be an artist, at least they would no longer put you in jail.

Do you think art must reveal or challenge societal issues?

I am absolutely convinced art mustn’t do anything at all. It must exist – that’s it. Art mustn’t do anything, trees mustn’t do anything, water and flowers mustn’t do anything, but all of them must exist because without them it would be tough for a human to exist.

What made you want to explore myths so expressly in your latest work?

Myths are the greatest thing in the history of mankind. In studying the world around us and in self-identification everything is penetrated with myth. Nowadays, we often consider myths to be disgusting – full of political motives – but they exist regardless and are in fact, quite natural. The fact that I more often deal with ancient myths instead of Soviet ones is connected to – in the words of Brodsky – "my infection of Soviet classicism", but I am happy to catch this "disease".

What do you think about when you approach a blank canvas? Does literature often provide the germ of inspiration that leads you to your work?

The artist is almost like a sparrow – he’s feeding from every source he can. These are just visual impressions from walking along the streets, visiting the museums, listening to music… an enormous variety of impressions. These cannot be expressed with words – it’s just a process. And, of course, literature is an important source. The fields for gathering the harvest of impressions are very big and the main thing is to make a good product out of this harvest. What am I thinking about in front of the white canvas? I have two difficult moments: starting the work and finishing it. I work pretty slowly during the very first and very last days. These days are really hard for me – I don’t approach a blank canvas for a long time, and then, after finishing, I don’t put my signature on the canvas for a long time either. It’s personal for every artist, but as for how it works for me – I’ve been pretty clear. When it comes to affecting the viewer and his feelings. I kind of stopped hoping for something. I just hope that he will feel just something. Sometimes the viewer’s perception is totally different from what I was seeking to express in a particular painting.

How do you feel about the political landscape in Russia?

During the communist regime the main feeling was hatred, to every power that used to exist – whether it was ministers or the church. It was like hating a killer, or a bandit. It was blind, never dying hatred, which was exhausting, with no way out. Now the main feeling I have is disgust. That’s it.

Do you have hope for humanity?

I do have hope. I accept the rules of the game, and I understand that human existence is totally useless when talking about the whole of humanity. But why should I lose hope? If a human being is able to rise from his knees to his feet – it’s beautiful. The contemporary condition is not natural, not good, but still – man keeps surviving everything. Yes, the killers, the rapists, the dictators and the bandits keep appearing, but until now humanity had the guts to fight this and survive this. I don’t have a single reason not to hope for humanity. I do not believe in its bright future or that there isn’t one, because the world will end eventually, but until humanity can provide its own physical existence, there are no reasons to think there won’t be any further evolution.

Vladimir Ovchinnikov: New & Recent Work will be on display at Erarta Galleries London from November 28, 2011 - January 7, 2012.

Text by John-Paul Pryor