In the new issue of AnOther Magazine, Hew Locke talks about how his childhood Christmases in Guyana watching masquerade bands inspires his artwork

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

“Christmas in Guyana wasn’t complete without a masquerade band. You would hear it coming in the distance – the high-pitched sound of a fife and a small snare drum. The band would move through the local area, going to places they knew they’d be welcome and could make some money. It’s a very powerful childhood memory. There were several characters. Mother Sally was a white-faced stilt dancer in a big dress and tall people would have to move telephone cables out of the way so she could come down the driveway. The Bull Cow was really disturbing, a character in a very crude costume with sharp horns. It would charge at all the kids, which was scary but exciting as well. This was a basic, simple thing, but it was a change from our everyday reality. We were living through the end of a tradition that evolved into something more associated with Guyana’s independence and Mashramani [its annual celebration]. When I’m talking about the band, I’m talking about personal memory, but layered on top of that are past histories, present realities and how the past affects the present. My career is like a net, dragging all these histories and memories together. Sitting here, decades later, it’s still vivid in my mind – the emotions or the fear, hearing the flute, the fife. The work I’m doing is trying to resurrect something. This is not about nostalgia. This is about the passing of time and how things change. We are what we carry.”

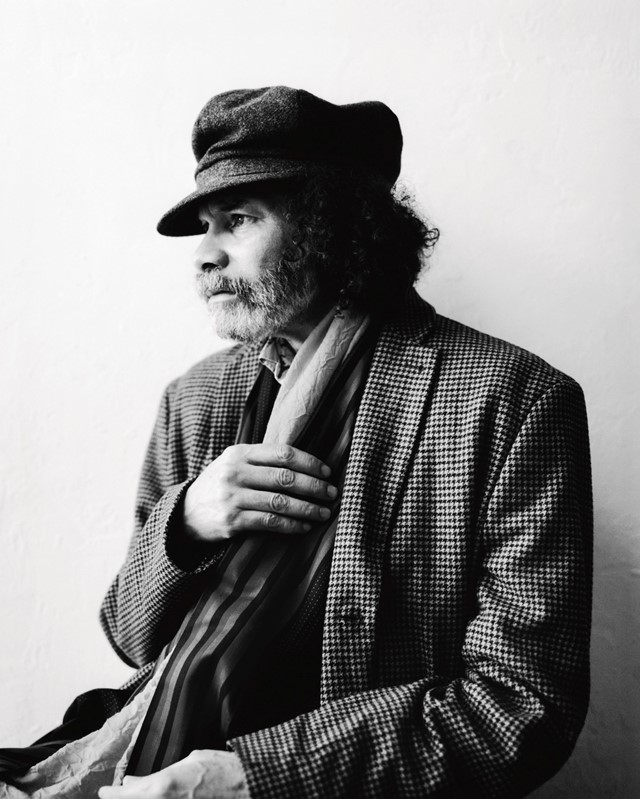

In the mid-1960s, a five-year-old Hew Locke and his family left Edinburgh for Guyana, arriving in time to witness the nation’s burgeoning independence. Now in his sixties and based in London, Locke works across sculpture, installation and painting to explore intersections of memory, history and colonialism. In 2022, Locke transformed Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries with The Procession: a Technicolour masquerade of almost 150 life-sized figures, as if frozen mid-migration, in robes made from fabric, resin and found objects, printed with antique sugar trade share certificates and imagery of dilapidated Guyanese houses. Wearing bright flowers in their hair and ornate masks covered in beads or skull depictions, they waved vast embroidered banners and flags. Their weathered costumes were suggestive of a long, arduous journey, in which visitors became active participants, weaving between the bodies and joining the march.

At the end of last year, Locke was awarded a public art commission to recontextualise the controversial statue of King Leopold II in Ostend, Belgium, and confront the country’s colonial legacy. This autumn, he will be celebrated with a major retrospective, Passages, at the Yale Center for British Art, Connecticut, examining his career from the late 1990s to the present.

Set design: Olivia Giles at Jones Management. Hand-printing: Merrick d’Arcy-Irvine. Special thanks to Nachum Shonn

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now.