As she unveils the first solo presentation of her work in over a decade, Ryan White meets the Norwegian photographer who made a name for herself capturing characters on the edge of civilisation

Mette Tronvoll has been photographing stories about time, place and identity since the early 90s. Her subjects have always been eclectic and unassuming, from seaweed farmers on Japan’s beaches to Norwegian men standing in a studio wearing nothing but their underwear, but guided by the same impulse. “I am not searching for interesting-looking people,” she writes in the notes of one such project, “but interesting meetings with people.” What’s most striking is that it feels like an archive we should know better, given its depth and clarity. Yet, outside of Norway, Tronvoll seems largely unknown. Perhaps her lack of interest in shooting fashion and commercial work can explain why.

“The thing is, I never worked with magazines, even though I wish I did,” she says. “I was so set on becoming an artist in the classical way. [When] I lived in New York from ’89 to ’99, there were some magazine presentations of my work, but that’s so far back that I don’t even remember names.” Owing to her current dissatisfaction with how the art world operates, Tronvoll jokes that now might be the time to reappraise this approach. “The art world has changed a lot since I started out. The museums, they’re emphasising entertainment; it’s not all about knowledge and these purist expressions they used to have.”

Tronvoll had her first museum exhibition in 1994 in Trondheim, her hometown, followed by a gallery show in New York, before participating in the first Manifesta 1 biennial in Rotterdam. Her influences from early on include the portraits of German life in the early 20th century by August Sander that she first discovered at the MoMA (where her work now sits in the permanent collection), as well as Thomas Ruff’s large-scale portraits in the 80s, and other members of the ‘Dusseldorf School of Photography’ – an influential collective of German photographers of which Ruff was part.

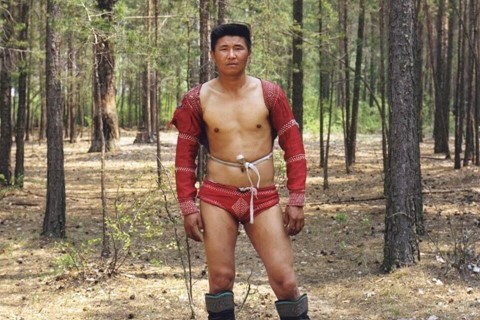

She’s travelled as far as Greenland, Zambia and Mongolia to make slow, in-depth stories, incurring, in the latter’s case, some of the criticisms photographers tend to now face when shooting outside their native homes. “They think that I came and [exoticised] strangers because I’m not Mongolian. To me, I never tried to be a social anthropologist. But, you know, I’m not going to say what other people say about it, because I feel that it was a real exchange.”

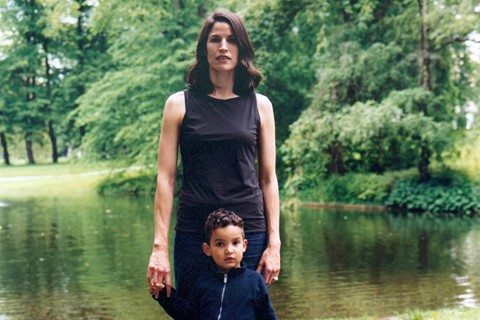

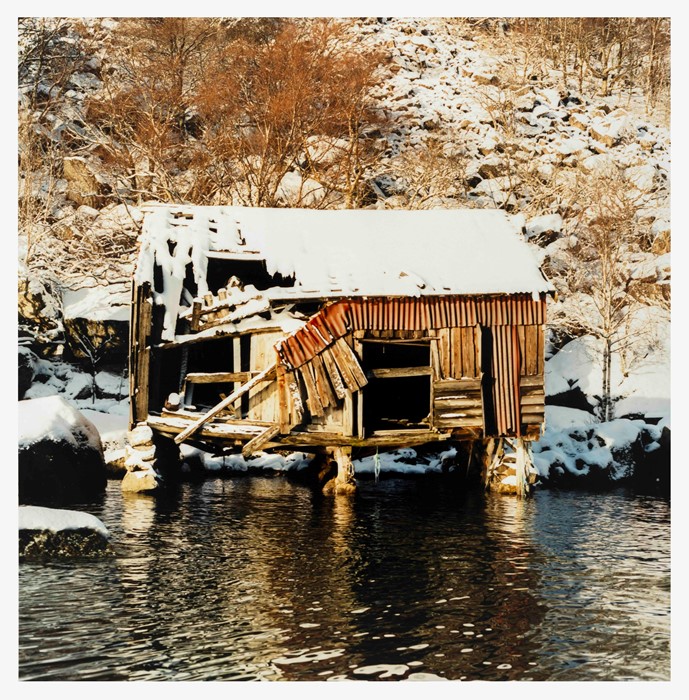

This latest show, Time, at Kuntsilo, a new museum inside a former grain silo, is the first solo presentation of her work in over a decade, and is firmly rooted in Norwegian culture. The show predominantly celebrates the natural beauty of Hidra, an island on the south-western tip of the country. It does this through epic sweeping landscapes and quiet portraits of its elderly inhabitants. Tronvoll also returns to photograph a few subjects from an old project, one shot at the beginning of her career, contrasting portraits of young women living in New York City against elderly women from a small village in Norway.

“I feel distinctively different, honestly,” Tronvoll says when asked how time has shaped her as a photographer since this project was first shot. “On the other hand, I do exactly the same thing, but I have changed formally. I know much more, and I’m not so stiff and inexperienced, but at the same time, I react to the same things; I have the same eyes, the same look, the same intentions, maybe.”

In its most granular details, Time considers a traditional world giving way to a modern one. The elderly fishermen in wooden boats, for example, are the last of their generation, with no one in line to replace them when they retire or pass. The images themselves have been printed in the darkroom by a dear friend of Tronvoll’s, one of the increasingly few practitioners left of this dwindling art form. Underpinning it all is the fact that this project was made possible by a grant from the Norwegian government, one of very few handed out anymore as investment in the arts dwindles. No one else, as far as Tronvoll is aware, has been a recipient since 2019. “I think all the political parties from left to right just agree that they don’t want to give it out anymore and that’s very sad.”

“It’s a cross point in our time,” she finishes. “It’s as if new is meeting old.”

Time is on show at Kunstsilo until 25 May 2025.