This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

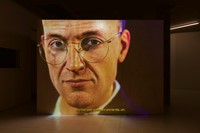

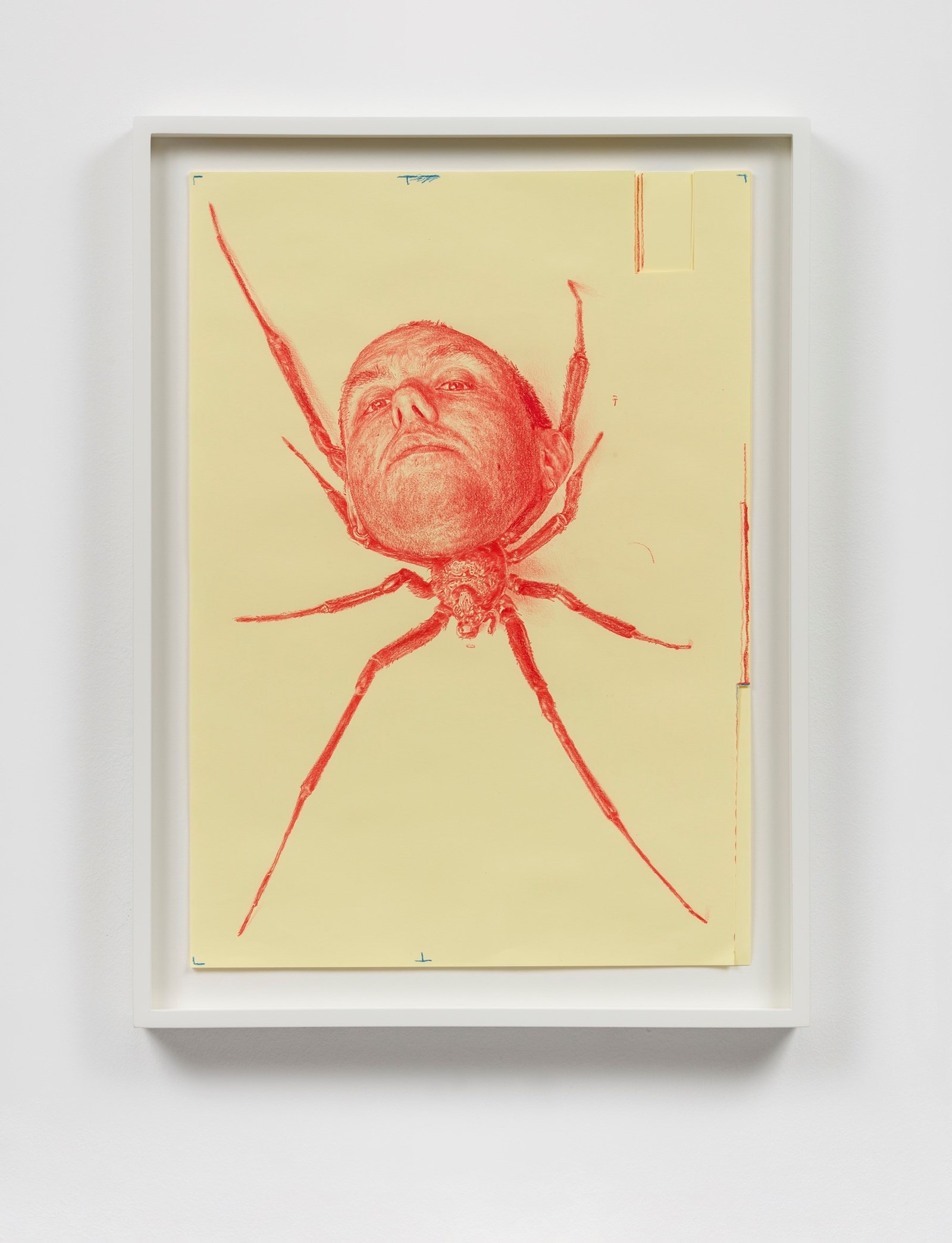

For the British artist Ed Atkins, life and work are inextricable. That is perhaps why his oeuvre spans multiple modes of expression: writing, but also vast, minimalist embroideries, intricate pencil-drawn self-portraits, CGI animation, installation, performance, singing, theatre and now, for the first time, film.

These are rarely presented in isolation — instead they are Gesamtkunstwerks, total works of art. The installation Old Food (2017), for example. On separate screens, a robotic CGI man, boy and baby cry; they float, run, lie prone or play the piano, all while weeping without explanation. They are the embodiment of melancholy. The backdrops are medieval or folkloric — a cabin, a woodland, a rainy alleyway ... Around the screens are hundreds of costumes from the Deutsche Oper Berlin — the absence of the bodies that might wear or have worn them is palpable; something is missing.

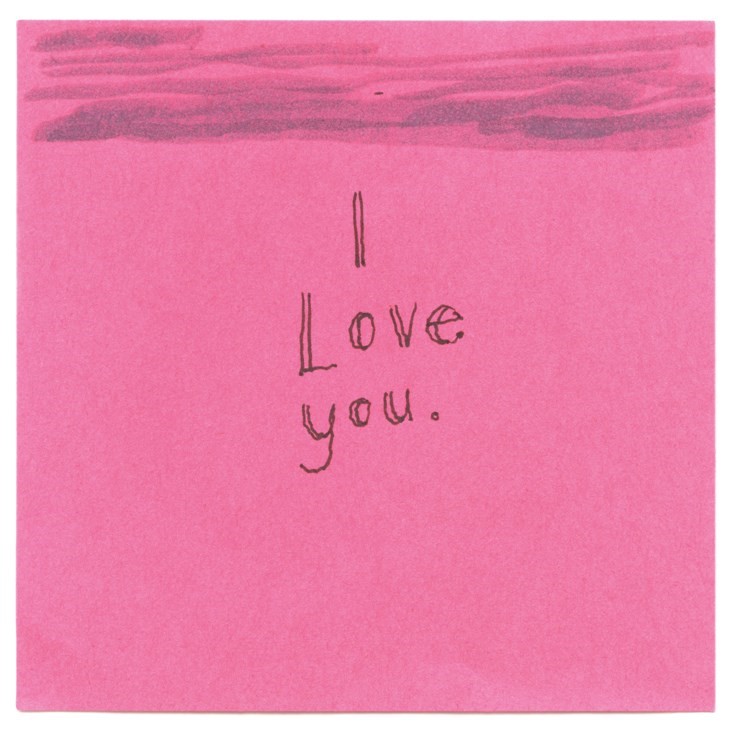

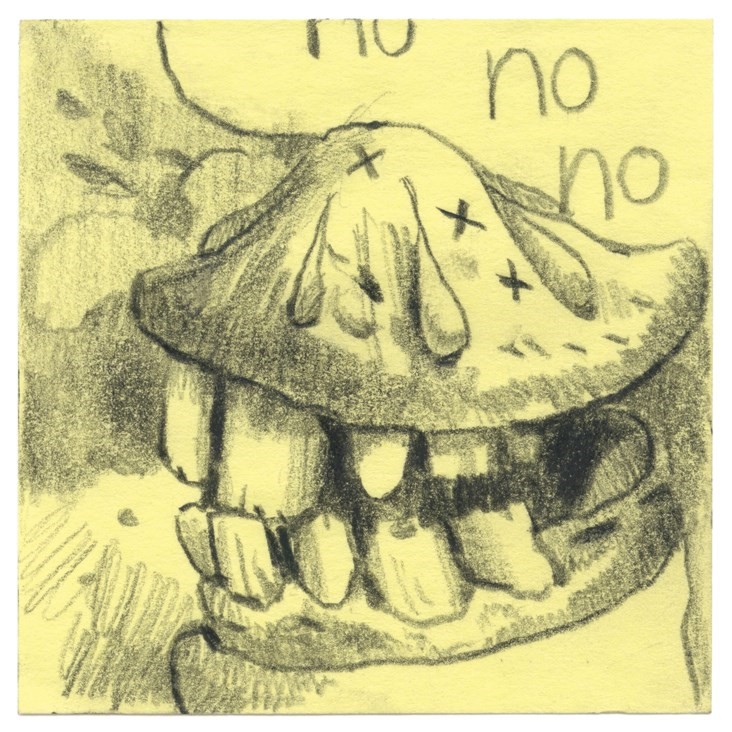

Tracing the often incomprehensible – human fallibility and failure, the concept of truth – Atkins’s work combines an uncanny realism with jarring alien bodies and places. His forthcoming survey show at Tate Britain defies any linear or logical arrangement, though his Post-it notes (bearing surreal scenes, originally painstakingly drawn for his daughter’s lunchboxes) are the heart of this exhibition. Flower, a trippy stream-of-consciousness memoir, is being published in tandem. Here, Atkins talks to his childhood friend, the actor Rupert Friend, about realism, the soul of an artwork and wraps bought from late-night pharmacies.

Ed Atkins: So this is the first time I’ve seen you for quite a while – although it’s just ‘in the face’ rather than in the flesh. We talk about one another’s work a lot. Rupert, you’ve always been, and still are, one of my first audiences for anything. The person I would want to see my work. Most recently that’s this new book, Flower. Sending that to you was very important because it is a weird, confessional thing, full of stuff you would know and recognise. It’s rare to have a friend that spans all that history and the peculiar decisions that have got you to a specific spot of making or desire.

Rupert Friend: And there’s an evolution – being present with each other for 35 years now. I’ve been there in the wings since you were doodling on napkins. So to see you having this huge show at Tate Britain is a thrill.

EA: I think we’re both allergic to the past, though.

RF: It’s true.

EA: It’s interesting in relation to this book, which is written in a confessional mode but has a historic accumulation of a sense of self. Or, in fact, an accumulating lack of a coherent sense of self … This survey show – calling it a retrospective makes it sound very historic — at Tate Britain goes back to 2010, and there aren’t many things that have been consistent through that time, things I have kept hold of. There’s my partner and there’s my friendship with you.

RF: So I want to ask you about Flower. Because to my mind it was, as I wrote to you, one of the most truthful things I’ve ever read by anyone. And I also know that there are stylistic choices and reasons things were omitted or included. When you write – that piece or any of your written works – do you adopt a character?

EA: No. I think part of it is that I don’t know who I am. I mean, I do of course, in a very normal sense. But it’s more a feeling of, if I interrogate ways of being, ways of speaking, desires, things, I can pull them apart, and I have a propensity to worry over the truth and falsity of myself. If I’m lying or not, or if lying and telling the truth are even remotely available to me to corroborate or not.

So is it a character? It’s not a developed anything, really – it’s me, but stylistically trying out a different, ventriloquised tone in myself and of myself. In the case of Flower, it is a deliberately, partially impoverished tone, a place to pronounce not-knowing. And there’s the syntactic blurting, and the weird, occasional flatness that also speaks simply to the pleasure of writing the text, the desire to explore it and explore myself. To be able to turn a corner very quickly in a paragraph between an obvious banality to some stinging moment of seeming sincerity. And then keep moving.

But you saying it was one of the truest things you’d ever read means so much to me. The peculiar thing about the book is that it is full of truth, and of course it’s a confection to a certain extent – but that truth contained in Flower is the truth of not having access to truth. The truth is a confession of ambivalence. Because that’s just what it means to write. You’re representing something that is always unrepresentable without massive compromise. I must say that it’s a great thrill that it will be published as non-fiction – which it is, but it is also amusing to me. It will be shelved with memoirs and autobiographies. It is kind of a memoir or an autothing, but there’s this asterisk at the end – “What does that mean in this context? What if the act of conjuring a memoir is assumedly fictive?”

I suppose it is a slight assault on the notion of the purity of a person’s memoir. You know when people in interviews say, “And then when I was six, I first picked up a brush and I realised I was destined to be a painter … ” This kind of mythologising bullshit. That was a big desire of mine with this, to get rid of all that sort of retconning shit. But I really do like eating these wraps from late-night pharmacies. I really do like Heinz Lentil Soup.

RF: But it is also a choice. It’s an editorialised process.

“There seems to be a consensus that my work is sad or depressing but I’ve never set out to make something miserable, just that it’s real, that you sense it’s real” – Ed Atkins

EA: Yeah. I’m not going to talk about how much I love my children. I’m going to try to avoid the tropes of so-called authentic writing …

RF: To me, the memoir, the diarist, is a conundrum. I’ve always struggled with reading memoirs, even and especially when they’re beautifully written. Because they feel presented. And in the world of film and representing real life – which it obviously isn’t – what we are searching for in a performance as an audience is some degree of truth. Unless it’s some very Brechtian thing, I want to believe that that is the person. I know they’ve got a fake nose on, and so does everyone else. But for this hour and a half let me believe. And the suspension of disbelief is of course, necessarily, a construct. So this search for truth or integrity – however we define them – is the thing.

EA: Totally. Even when it’s presented as raw. I got mildly obsessed with the notion of realism in recent-ish history and how, via a lot of kitchen-sink dramas, particularly in Britain, realism has become sort of synonymous with misery. The idea that the more miserable something is, the more real it is. Somehow Game of Thrones feels realistic because people are beheaded or because it’s gross, there’s shit in it, and sex, and the surprise murder of anyone, however important a character they are – that those things are the signifiers of realism is insane. If there was any conceptualisation of Flower – or the things that I’m looking for in cinema or music – it’s this peculiar … not disappointment but an unspectacular attention to the fact that a lot of our lives are rather boringly OK. With caveats of course. Eating a wrap, walking down the street – it doesn’t have drama to it, it’s not a psychological mode, it’s not dramatic, it’s not for representational purposes, it’s not couched or reframed as important, interesting. It’s not, “What’s my motive here while I’m eating this wrap?” It’s just eating a wrap.

And maybe it appears miserable from the outside. But maybe it’s not miserable at all, it’s evidentiary. Or maybe it’s just like noise in your being. And I’m fascinated by that space of truth. I might just shout “clog boggler” over and over if I wanted to – it might just come to me. Things like that too. Unintelligibles. Or you might just start making up a song …

RF: I would record the song and I would send it to you. That’s what I would do.

EA: Yeah, you’d send it to me. And obviously there is a pleasure in writing those things down and elevating them to significance, insisting on their weird veracity.

RF: Yes, by publishing them in a book. By doing that you shine a light on them and you change them. By putting a camera on somebody, what they’re doing changes because it is now being observed. And that person walking along eating a wrap, if you put a gospel choir singing over it, now we might feel somehow exalted, or sorry for them, or nostalgic.

EA: I was watching something on Netflix, I can’t remember what it was now, but I hated it — it felt palpably engineered, algorithmically tested. Everything was polished to this pointless sheen. Regurgitated buff that feels so tested. There’s this worry within the creative industries about AI, and I do understand it, but maybe there’s a challenge in the models of AI that we’re talking about – maybe if you don’t want your work scraped and used you should write really weird stuff that isn’t for everyone. Make weird things that are not really like anything else, or confuse the conversation, the data. Because what AI does is aggregate and it schloops it all together – it has to base everything on things that already exist. And there is a resignation to even worrying too much about it – at least currently. Maybe it’s stupid, but there’s a part of me that has faith that it will never be able to rival actual human invention – because it’s never going to make up a song like the songs you make up and send over … why would it? There’s no groupthink to it?

RF: Yes, if you typed into AI, “Please make me a song in the style of the ones that my friend Rupert sends me,” you wouldn’t get anything. So what you’re saying is, deny AI the echo chamber of predictable content.

EA: If you’re predictable enough for it to know what you are saying so that you are satisfied with the results it feeds you, there’s something a bit wrong.

RF: So this show is going to be visited by people from all over the world. More people than ever are going to get a sense of at least the past 15 years of your work. If people started to go, “Oh, Ed Atkins, the guy who does fill-in-the-blank,” would that make you think, “I need to change everything I’m doing”?

EA: No. I was thinking about this the other day. I occasionally stumble across things that are conspicuous copies of something of mine. I don’t care. Whatever the copyist thinks they can take doesn’t diminish what I think the work is, which is perhaps a completely untouchable thing.

It’s maybe naive to say, but it’s the equivalent of saying, “Well, it’s un-scrape-able or un-crawl-able,” or whatever the current vernacular of AI is. You could copy it exactly, but it would be soulless. And it would not be from me, it would be from a determined rendering of what seems to be me. But that requires the things that I make to be soulful and real and truthful – with all the caveats to truth mentioned – which is certainly not the case all the time. I don’t mean to sound woo-woo about it, but if there is something that you can feel in a work, or a performance, or any kind of art, it is irrefutable and could be plagiarised and stolen but never spoiled, somehow.

RF: I completely agree. I was looking up people copying the bass solo from [Paul Simon’s] You Can Call Me Al yesterday – the things you do when you’re trying to feed a baby and you can’t really focus [Friend’s first child was born last year]. And I watched three or four guys who were brilliant technical bass players but you felt nothing. Now, it’s a truism that replication gives you the form of the thing maybe. The lines in a drawing or the music of a thing, but it also lacks what AI lacks — the soul. And we don’t know, as humans, what the soul actually consists of. People have spoken about a weight in grammes that leaves your body when you die, they’ve talked about, obviously, consciousness. But to me it has something to do with connection. That tingle down your spine when you feel someone speak to you through their art, their actions or just their presence. That can happen from beyond the grave …

When I think about the three things that are the most interesting about humans, and that separate us certainly from machines, it’s the soul, the imagination and dreams. There are, in my opinion, more than six senses. So I’m not finding what you’re saying woo-woo. It made me want to know something – when you look at a real retrospective of an artist, as in their entire life, Picasso as an obvious example, and [curators and critics] talk about their different periods, do you think those artists consciously elected to change direction or were they following a natural evolution of their practice?

“When I think about the three things that are the most interesting about humans, and that separate us certainly from machines, it’s the soul, the imagination and dreams” – Rupert Friend

EA: I think it’s a bit of both, but I often think of it more as self-sabotage. The discomfort around people agreeing that the thing you’re doing is good – the cruise, the plateau. I certainly feel it a little bit, like I need to break the cycle, break something. I need to feel radically different and find a new outlet that I can take as seriously and feel as committed to, even temporarily.

I suppose that I fantasise, and I don’t know enough about why these artists made certain moves, but maybe it is about re-finding some relationship through a kind of destructive impulse. About stripping it back again, with the faith that the only thing that matters to begin again is me. And I have to trust that that’s what it is, so I’ll risk it and I’ll do this thing.

RF: There’s a quote I love by Martha Graham that goes along the lines of, “When you do something it is necessarily original, because it’s coming through the filter of you. And there’s only one you.” If I dance a dance and then you do the exact same dance, it cannot be the same. So, with copycats, have they made something else by virtue of having copied you? It’s like a forgery — a perfect forgery is not the same as the painting, but doesn’t it have value?

EA: To be clear, this experience of people plagiarising my work is very rare and hasn’t happened for a while, and maybe that says something about receding relevance, ha. But I’m not disposed to being jealous of people and I think that is to do with a sense of, “Well, I’m me.” There’s no grass greener on the other side.

RF: But that’s a very bold thing to consider. Because that is how to avoid all the petty lower vibrational things like jealousy, insecurity and bitterness. Because there is only one of all of us, and we all have something amazing in there somewhere, I believe. Do you remember that feeling turning on at a certain point in your life or was it always there?

EA: I can’t remember, so I suppose it was always there to a certain extent — not quite having time for being jealous. Or not knowing what that would even be in the context of making this kind of work. Because there were a lot of things to want instead, to want from myself. Because jealousy, what is that?

RF: There are fascinating studies, when you get into the development of the ego and why it developed as a self-protection method – the ego loves to be placed in a hierarchy.

EA: There is the idea of owning our own failures or repulsiveness in my work. Or leaning hard into them. The nuance, the fallible, the insuperable, the error, the glitch, the thing that is not about consistency or coherence. It’s this wrongness. There seems to be a consensus that my work is sad or depressing but I’ve never set out to make something miserable, just that it’s real, that you sense it’s real – even if that’s through the absence of a coherent narrative.

Therefore I’ve tried to work out what that is, and I think part of it is dwelling on the fallible, dwelling on the mortal. We’re going to die. The feedback loop of that, back to a problem and an error – the body, all these things that start to give form to me, to an individual. Which is why one of the things I wanted to ask you about is live performance. Obviously you mainly perform for film. It’s like a performance for camera, but they are nevertheless live performances. And the very few times that I perform something — usually a weird singing thing — the reason I want to do it is the feeling then and there, right then. The liveness. I’m not thinking about it as a recorded thing for posterity, but rather this feeling of trying to be present. And trying to invent situations that really push you to be as present as possible.

There are other ways of engineering situations where you must be very present – in a dubious way, not preparing for a lecture for example. Just seeing what comes up and allowing myself to be surprised by that. Does that exist in, not necessarily a method, but what it is to perform for the camera? Or to perform more generally? Is liveness a key desire in you?

RF: To start, one of my goals is to ignore the camera, not to perform for it, and let it come and find me if it wants to. But I can’t really be doing with the actors who are constantly trying to look good in front of the camera or get the best light. To me, the actors I admire are physicalising the imagining of a truth. And then trusting the technicians and artists around them to capture that. But not considering it their responsibility to deliver that as you have to on stage. If they can’t hear you at the back of the theatre, you’ve failed to deliver the play to the audience.

EA: Which essentially means that your toolkit, the things that you can call upon, the feelings, the ways in which you can perform, are infinite when you’re not performing for someone to hear. When the boom operator has to make sure they can hear you, rather than the internalised mechanisms of theatre performance.

RF: They both have technical elements, they both have artistic elements and creative elements. But to me they’re completely different. And one of the fascinating things about a camera, and why I love cinema, is the way it can sneak up on somebody and just be with them while they listen. Or be with them while they receive news. And that is a really fine art to behold. When it’s great, to me, it’s the ultimate make-believe. Because there is no ‘presentation’ in the stuff I like to watch and, I hope, do.

It’s when the actor is just present. Watching somebody grapple with something, without exposition, without dialogue, without helping the audience along, is riveting to me. On your classic black box stage, I have to say, “Oh look, a warring army is coming over the hill.” There isn’t one, but if I don’t say that, you’re not going to see it in your mind’s eye, right? Whereas the thing about cinema that’s so powerful is I might just hear that army and see a guy as he waits for it to come. And I don’t know whether he’ll be happy the army’s coming, or terrified, or what. That’s so exciting to me. It’s so nuanced and under the skin.

EA: You were fantastically supportive and essential to getting to this point with this film that I’m editing now with the poet Steven Zultanski, my collaborator. So much of that was discovering how, in moving-image-making, you are surrounded by tech, and the three hours it takes to make sure the natural light is bouncing nicely through the windows, all this stuff, essentially is to create situations of fastidious realness. Which is exactly like you said, the opposite of theatre, which is stripped bare of a lot of this tech or paraphernalia. So you could easily imagine, or fantasise, that the theatre affords purity – but of course it doesn’t. It’s this souped-up, amplified thing that has to be in the machinery of the body of the actor versus just pointing the camera at someone as they listen to someone else and they are responding. I found the set and the making so exciting.

You once said to me that actors are on many different shoots, different sets, they work with different teams but, potentially, directors have only been on their own sets. That was a great catalyst to help me depend on other members of the crew properly.

But I think, at least in relation to performance, in relation to liveness, all this technology is there to italicise, to pay extra attention to the tiniest truths that are expressible. That’s not a truism about Marvel cinema or whatever, but it’s about what’s possible in front of the camera, and in front of the microphone – it is so extraordinary.

“A master is able to feel the right decision to make out of the many thousands. That’s what any art form boils down to – choice” – Ed Atkins

RF: And shining that magnifying lens on smaller moments. That’s where cinema does something I’m not sure any other art form can do because you can get into the nooks and crannies. You can just have a ripple on a puddle and we know a T-rex is coming.

And theatre can be amazing, but you hit on something astute – the engine of theatre is the body of the actor. That is the machine. And a great theatre actor is an athlete – they need to deliver phrasing most of us don’t have the breath for. They have to stay present for two hours, sometimes performing every single word. And the presence thing is really the keystone of this conversation, but also definitely what I’m interested in. Because with two actors on stage, or on film, or in a performing piece like yours – there’s presence.

It’s literally, “Are you present with what is in front of you?” This could be the audience, your nerves, the sweat running down your back, the cold, the fact that the other guy smells funny. If you’re present with it, it’s completely riveting. And what separates amateurs from professionals is that the amateur tries to present something that they have prepared. The professional comes prepared to be surprised, prepared to pivot.

EA: It seems so simple but it’s the most admirable and complicated thing. You could say this about any person, any art – understanding the difference between a rote amateur or novice painter and someone who’s working in some absurd late style is to do with the confidence, the simplicity of the decisions that are being made. It’s not about this demonstrable smartness or upfront research. A master is able to feel the right decision to make out of the many thousands. That’s what any art form boils down to – choice.

RF: And it comes back to what you said at the beginning about the soul of the piece. When you look at a piece of art, or watch a film, or listen to music, or read a written piece, you get a physical feeling – a drop in the gut, or you’re reminded of a terrible time in your childhood, or joy fills you. Anything else is a print of that work, a facsimile – it leaves you feeling quite cold and uninterested. We’ve had the Ice Age and the Bronze Age and the Information Age, and I don’t know what they’re going to call this one, but it’s clearly going to centre on this notion of machines and humans merging. The Singularity Age, perhaps. Maybe AI had to be invented, to remind us of what is in fact so genuinely singular about artists, but also humans. That we have the capacity to touch this deep place, hence the phrase that we are “moved by something”. AI doesn’t do that – yet.

EA: And the challenge is not to say, “We’ve got to ban AI,” or control what it has access to. It’s to reinvent or re-tap into a sense of making things that feels singular and untouchable by any external, rapacious thing. And even though you’re familiar with my work, I hope you’re surprised by the show. Because you tend to see one thing at a time – a few things or a smaller, commercial gallery show. I hope this time there’ll be a reason to spend a good few hours immersed in this thing, and to see the way the works interrelate or accumulate, because they’re not arranged chronologically. If anything, the works are arranged to clash against each other, to transform one another by proximity. The accruing is decohering, I think. It’s not necessarily news, but I think as an experience the survey show’s cumulative effect can’t be guessed at.

This new film [its name is unannounced] made in collaboration with Steven is a big part of that because it’s finally using my father’s cancer diary – his death diary. I’ve shared bits of the diary itself with you in the past. And you know the script as well. But that feels like a capstone on going into the past, allegorising according to the future really, because the second half of the film, apart from the reading of the diary, is the re-enacting of a role-playing game I play with my daughter – the ambulance game.

RF: I’m so excited to see this film, because this is where our two fields start to converge for the first time – this is what we’ve been doing for a living for 20 years. Seeing this new evolution of you as a director feels pivotal to me and excites me. I’m so looking forward to seeing it as a part of this survey show. It feels momentous.

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now.

Ed Atkins is on show at Tate Britain in London until 25 August 2025. Flower by Ed Atkins is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, and is out on April 10.