Drawing from found images, film stills, religious iconography and personal photographs, Marcus Leotaud’s new paintings focus on the twilight hour as a metaphor for the in-between

“I’m interested in the missing parts … in the gaps and in those moments where we fail to see each other clearly,” says artist Marcus Leotaud. In his new solo exhibition, Between Dog and Wolf at the Bomb Factory, Marylebone, Leotaud – who grew up between Trinidad and the UK – uses painting to probe the limits of visibility: of what is shown, of what is withheld, and what it costs to be seen at all.

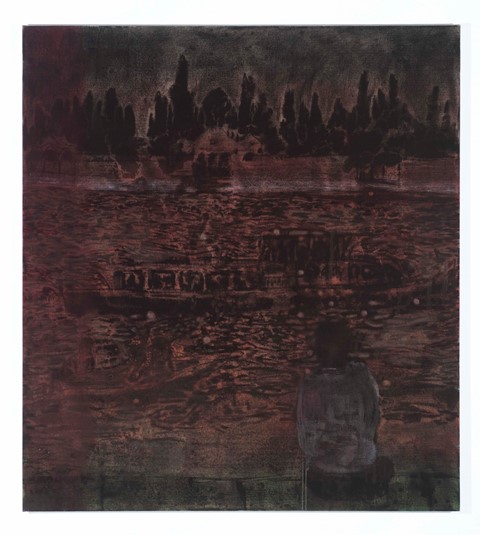

Large linen canvases hang under low gallery lighting, their matte surfaces drinking in the streetlight that filters into the gallery. Veiled in bruised reds, oranges and purples, the painted landscapes appear softened and dissolving into dusk. As the eye adjusts to the subdued palette and textured surfaces, faint impressions of barely-there figures and forms begin to emerge. In one painting, two lovers are locked in a passionate embrace, while in another, an ocelot prowls with its piercing gaze locking eyes with the viewer. Elsewhere, the waters of the Venice canals ripple and fade, as if caught in an eternal ebb.

The exhibition attempts to offer a meditation on twilight, and not just the fading of light, but the slipping of certainty in the twilight hour. The title comes from the French expression entre chien et loup, referring to the hour of ambiguity when “you can’t really tell what you’re looking at,” Leotaud explains. “Is it something friendly? Is it a threat?” The phrase, like the work, holds a contradiction in tension, alluding to that brief moment when you can’t tell if what you’re looking at is friend or threat. Leotaud insists on this ambiguity, explaining: “I don’t feel like I’m trying to deliver a specific message.” The twilight hour becomes not just a setting but a metaphor for the in-between: a space in which Leotaud is keen for his paintings to inhabit rather than resolve.

In the studio, Leotaud’s paintings often begin with found images, from film stills to religious iconography and personal photographs or scenes from memory. “Some images are personal,” he says. “Others come from films such as Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). One painting is a scene just before the main character kills the girl he loves.” Biblical scenes like Judas kissing Jesus are also referenced, not for their religious significance but for their narrative power. “If he [Judas] had just waited a bit longer, he would have seen the resurrection. But he couldn’t. That kind of moment – the just-before moment – is what I keep coming back to in the paintings.” These ‘just-before’ moments animate the exhibition’s emotional weight. The works are figurative but resist clarity, as if deliberately withholding full comprehension. “The paintings themselves carry that sense of ambiguity,” Leotaud says. “I’m not trying to spell everything out ... everyone brings their own interpretations and I like that.” His embrace of contradiction is central to his artistic practice: “It’s part of the struggle: how to say something and be understood, but also not be fully understood.”

The canvases themselves are quiet, shimmering meditations. Leotaud works with natural materials, using linen, pigment and gelatin glue to create matte surfaces that absorb rather than reflect light. “It’s very matte,” he explains, “so the colours come through [onto the canvas] differently … mostly, it feels like the light is just being pulled into the surface.” In the soft-washed hues of blood reds, forest greens and dark violet purples, ghostly figures emerge. This ambiguity is more than a formal strategy; it speaks to deeper emotional and spiritual concerns. Some of Leotaud’s landscapes draw from his Trinidadian upbringing, where encounters with the natural world were marked by danger. “In Trinidad, the animals are extremely shy … being seen means being killed.” His paintings capture not the natural world itself, but the aching desire to connect with it: an intimacy both longed for and out of reach. “I think the two main themes are intimacy and inaccessibility,” he reflects, “whether with people or with the natural world.”

In some of the oval-shaped canvases, the paintings play with ideas of repetition and time. The same scene rendered at different daylight hours or in different states becomes a study in how perception alters meaning: a non-linear unfolding where memory, light, and emotion circle back upon themselves. “I made a series of the same scene at different times,” Leotaud reflects, “to see how the light or atmosphere could shift the whole feeling.” Even the material process reflects this idea. Working with glue-based distemper, Leotaud creates textures that seem to hold the trace of each gesture. “I’ve learned that rubbing the surface builds it up more than brushing it … it creates these areas that feel almost like stone.” Like memory, these surfaces are layered, rubbed down and worn in. They are never fixed.

What does it mean to dwell in ambiguity or uncertainty rather than resolve it? Can intimacy survive without full recognition? Leotaud insists on a certain opaqueness, and that seems to be at the very point of his paintings. His paintings live in those gaps, in the hazy moment of trying to distinguish between dog and wolf, between knowing and not knowing, between the present and what comes next.

Between Dog and Wolf by Marcus Leotaud is on show at the Bomb Factory Marylebone in London until April 20.