The German artist Thomas Ruff has been challenging ways of seeing for 30 years, questioning the pre-supposed validity of the photographic image and engaging us in a game of smoke and mirrors where our fantasies and projections complete what we

"All photographs are there to remind us of what we forget. In this – as in other ways – they are the opposite of paintings. Paintings record what the painter remembers. Because each one of us forgets different things, a photo more than a painting may change its meaning according to who is looking at it." – John Berger.

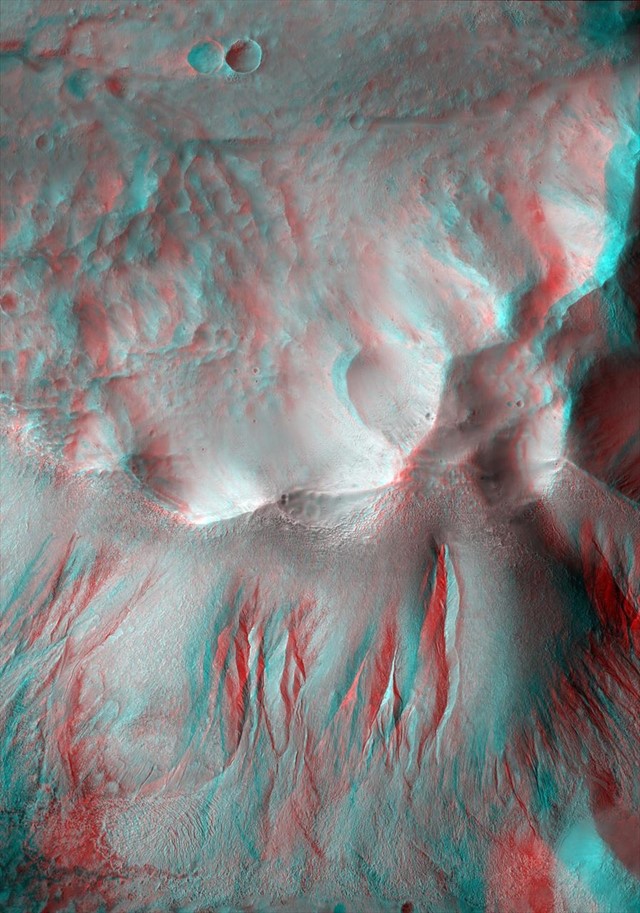

The German artist Thomas Ruff has been challenging ways of seeing for 30 years, questioning the pre-supposed validity of the photographic image and engaging us in a game of smoke and mirrors where our fantasies and projections complete what we believe we perceive. His latest double-whammy at The Gagosian, London, focuses on his huge, sometime three-dimensional, colour-saturated close-ups of the surface of Mars and his celebrated series of images from porn sites, which take some of the most graphic, voyeuristic sexual excesses and lend them an ethereal, almost classical aspect. These two main strains are complemented by works from his "jpegs" series – which blow up and reveal the glitch-heavy grid-like DNA of the digital image – and "subtrats", his gloriously psychedelic abstractions of Manga cartoons. While together the shows provide a cohesive overview of his artistic concerns for those uninitiated with his work, AnOther chose to talk to him chiefly about his most recent series ma.r.s – reworked satellite images of such imposing size that it feels almost as if one could walk into their heavily cratered, lonely landscapes. Here, the artworld legend discusses his early memories, the potential manipulation of human history via Photoshop and why every image is a mirror of its beholder.

Can you remember the very first images that fired your imagination?

That’s a hard question. I have to confess I have no idea. I guess I had my first telescope just before puberty. I tried to look at the sky but that was very disappointing with the small telescope, so I was looking at astronomy magazines, and there I saw the really interesting images – these things you cannot see with a telescope; that you need rockets and satellites to see.

Where did that fascination stem from and why has it endured?

Maybe it’s just a fascination with cosmology – the fact the evolution of the stars and planets started with a big bang. I was born in 1958 and the 60s were very optimistic in terms of technology. I read magazines about how by the year 2000 we would be flying around in cars that were no longer on the street. There was this kind of technological fascination and strange optimism – everybody thought in 20 years we would have solved all the problems of people on earth and have machines that could make planetary voyages.

What is the significance in going so close-in on the surface of Mars, and what are your key concerns in this work?

The photographs are fictional. I change the perspective from a satellite view to an airoplane view, so this is a vision that astronauts in probably 20 or 40 years will have. So, it’s a fiction and, at the same time, it’s realistic… We have the technology to look at things much more precisely now, and it is fun going very close on a small print trying to find the smallest details of the landscape – then looking at the impact of size, creating a kind of different physical presence. I think the big question of photography right now is who’s taking the photograph – is it the photographer or is it a machine; a satellite or the high-rise cameras that are all over the cities? It’s the question of authorship. The next question is the question of altering such images now that we live in the time of the digital photograph – can we believe the image; can we trust the image?

Do you see our relationship with the image getting to the point where we might have digitally-enhanced vision? Who then would be the author, and indeed, the viewer?

I think I cannot comment on that, because technology just goes on and on and you cannot stop it – you cannot step back from it. People think of new technology and say it will make life easier, but I think a lot of people will be lost in this new world and will not… okay, they will survive but they will be completely confused.

Why do you reveal the DNA of the digital image in your blown-up series of JPEGS?

I just want to make it obvious. For fourteen years we have had the digital image, and it has such a different structure to analogue film. The structure is the pixel, and now you don’t only have the pixel but you also have the compression to make them smaller – to send them via the web and make the distribution higher. People are looking at these images and thinking they are true, but they don’t think about what the image consists of, they take the photograph as transparent and they mix it with reality – our brain is very brilliant at interpreting even the lowest resolution, it creates images. So, these questions of mine are very much about the structure of photography but there’s also other factors – even the compression gives a structure to the image, and then you have the distribution. In that instance, it’s not a machine that produces the image but it’s software, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s software or a machine – it’s not handmade, it has been done for us and we cannot control it.

What’s your reasoning in saying to us: "Look, it’s not real. Don’t accept it as reality." What’s the purpose?

I want to tell people to be careful if you look at photographs – don’t believe everything that you’re looking at because it’s either a pre-arranged reality or it’s reality, yes, but then afterwards the image is altered. I don’t know who said it, but someone said that in the future the illiterate is someone who cannot read photographs, because he can be manipulated in any way.

If history is made up of digitally manipulated images it will be rewritten, and it will be impossible to ever find the original; the truth…

Yes, it’s like 1984.

Do you believe you are completely alone when you experience an artwork, or do you think there’s a point where one can have a communal perceptive experience?

I think maybe there can be a kind of common sense, but I don’t think there can be an identical view on one image. We are all individuals and we all have our own experiences, and we have developed our consciousness and dealt with our lives in different ways. They are small graduations but, yes, everybody’s unique and everybody’s unique belief or thought comes into play – the images are all mirrors, we all see what we want to see.

Thomas Ruff: ma.r.s runs until April 14 at Gagosian Gallery Britannia Street, London, and Thomas Ruff: nudes runs until April 21 at Gagosian Gallery Davies Street, London.

Text by John-Paul Pryor