In 2004, Jamie Shovlin caused an art world rumpus when his debut show, exploring the work of prodigal schoolgirl talent Naomi V. Jelish, was bought up by Charles Saatchi and then discovered to be a hoax...

In 2004, Jamie Shovlin caused an art world rumpus when his debut show, exploring the work of prodigal schoolgirl talent Naomi V. Jelish, was bought outright by Charles Saatchi and then discovered to be a hoax. Similarly, German glam-rock band Lustfaust, whose memorabilia formed the basis of Shovlin’s 2006 show, never existed. So far, so Nat Tate. Yet this is not a series of practical jokes designed to make the cognoscenti look foolish; rather Shovlin’s work occupies a rarely traversed zone between truth and fiction, creating pieces that force viewers to question both what they’re actually seeing, as well as the established criteria they use to accept a thing as real.

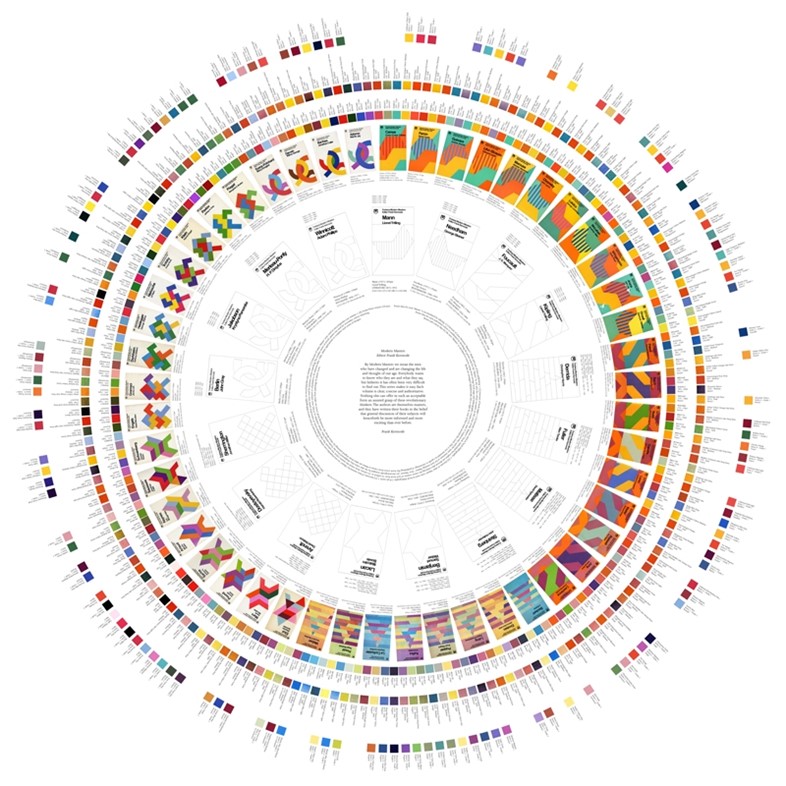

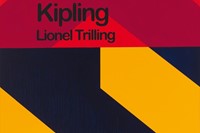

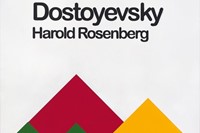

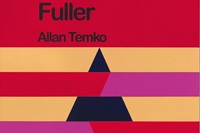

Given his history however, it is understandable that one walks into a Shovlin show with a heightened sense of suspicion, yet in his latest, Various Arrangements, opening this week at London’s Haunch of Venison, everything appears to be above board. The walls are filled with recreations of Fontana Modern Masters covers, representing works scheduled to be published in the mid-80s, but which never materialized. The Modern Masters were striking for their cover-art, colourful linear abstractions that were individual to each publication, yet which had no relation to the Master whose philosophy they housed. Fascinated by the fundamental human desire that searches for connections even where there are known to be none, Shovlin set about creating an elaborate point scoring system using the “data” of the existing works to “work out” how the absent ones would have looked. Here AnOther speaks to Shovlin about the slippage between truth and reality, and how meaning can be extrapolated almost accidentally by dint of human inclination…

Where do you feel this series sits amid the "art hoax" oeuvre that people perhaps best know you for?

It’s a question of structure. When I’ve done archives of material that sit on the line between fiction and truth, I’m less interested in the idea that something might be true or not, and more interested in how it goes about substantiating its story. So whether that’s creating a false history of a band, like the Lustfaust project, or whether it’s creating an archive about a friend of mine called Mike – it’s the fact that if you equalise the viewing circumstances for both of those things, they become effectively the same. What is the slippage between them that means one thing is taken as real and one thing isn’t? And in my work I’ve always liked to have a theoretical idea of how things should be and then apply that knowledge or theory to actual things in actual time.

So you were researching an entity that is based on a reality – Fontana books existed, these books were going to exist – so why was it important that the covers be fashioned out of an self-created equation which was fundamentally flawed?

Ultimately I wanted to create a system that would be a tongue-in-cheek version of more rational objective means. That’s where the heart of the project was – an attempt that was doomed to fail but that failed in a beautiful way, and in failing actually provided more humanist answers than a conceptual and mathematical process. And I really liked the idea that I could use these books as an analytical tool, even though they were clearly never intended that way. The idea of conferring meaning on material that patently does not have it was always really appealing. And then there was the question of the missing books – the reason those books didn’t exist is just an oversight in publishing history, there’s no significance, no meaning. But it gave me this reason to conduct the analysis that had been my focus at the beginning.

Do the designs have any relationship to the authors of the books that they are portraying?

No, but I was always interested in the idea that you could read a relationship. When I first saw these books, I was making interpretive relationships, and then I met Fontana editor Frank Kermode and Mark Dempsey, who was the art director of Fontana from the mid-70s onwards, and the first question I asked was if there was any relationship between these two things, and they said not at all. It was entirely random, but there’s still a human impulse to connect the text and image in a meaningful way.

And there’s something so fundamental about books as well…

Yes, you read meaning into it, it’s significant, or it has implied significance. It’s strange now for me to even think about this, because it’s very difficult for me to disassociate myself from the creative process. Every layer I finished would be just just colour and space, but the final part of every layer was to put the text on, which signifies its connection. Until that point it’s a fairly benign structural graphic design, and then as soon as that text is there it finally means something, and it doesn’t really, but by putting those two things together, it starts to have a relationship, whether you like it or not.

Various Arrangements runs until 26 May at Haunch of Venison, New Bond Street.

Text by Tish Wrigley