Ahead of the launch of his new book, Damaged Negatives, AnOther speaks to acclaimed photographer Glen Luchford...

Photographer Glen Luchford spent the nineties shooting for magazines such as Vogue, The Face and Arena. His classic and observant sense of narrative became one of the signature aesthetics of the era; part Robert Doisneau, part George Brassai, his images are clean and clear, dramatic in their understatement and nostalgically realistic about the impact of modernity upon latterday living.

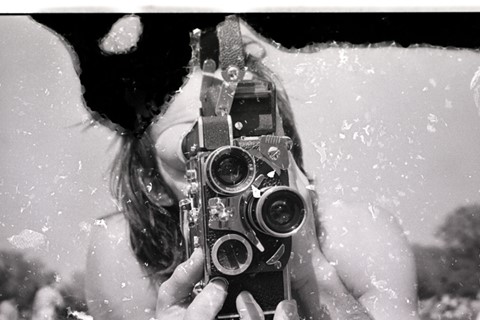

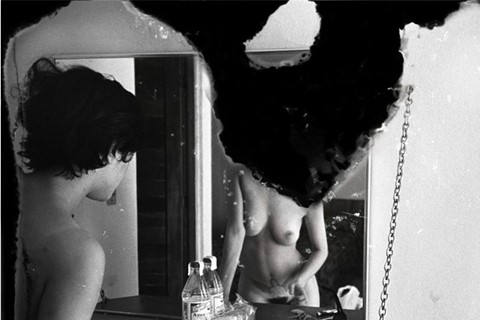

His new book Damaged Negatives is, on the one hand, his own idiosyncratic take on the work he did during this time. On the other hand though, it is an Act of God. “I put the images in storage for two weeks,” Luchford explains, “which turned into two months. The entire storage unit flooded and the owner didn’t tell anyone, so by the time I arrived, the images were just mostly gone or in a state of high deterioration. There were flies and mould everywhere. On a sub-conscious level, you have to ask why I would ever have put them in such a ridiculous place,” he continues, “considering one print just sold for £25,000, and I lost thousands and thousands of negatives.”

The book then is an exhumation of that wrecked archive. Figures – including a young Kate Moss – swim mystically in clouded and chthonic black and white, as if reflected in ancient mirrors or trying to interject from a different time. On some images, the damage manifests itself like burnishing and cigarette holes; on others, faces are obscured entirely by whorls of oxidation that lend the sitters and their environments an arcane type of poetic importance.

"Fashion is totally industrialised, and I’m trying to entertain myself as part of the mechanism"

“I simply can’t take myself seriously as a photographer,” says Luchford. “Never could. And this act of sabotage just painfully highlights that, each time I look at them.” There is a modesty and a self-depreciation to Luchford that stands out in his work, and is even more apparent so in these ruined pictures. Subjects appear uncomfortable, distant, at times anonymous, thanks to the havoc wreaked upon each tableau by the encroaching rot and disrepair. The transition from laughing model to something more Lucian Freud-esque was of course entirely unintentional, but there appears to be an agency to the anarchy – where the prints have decayed, that artistic foundering seems almost intentional.

“To me it looks without style,” Glen Luchford says of his work. “Fashion is totally industrialised, and I’m trying to entertain myself as part of the mechanism. Clearly, we’re just here to sell clothes. But sometimes we find the images transcend the medium, which can be very nice. I suppose, in some peculiar, twist-of-fate way, these images do that,” he adds. “They’ve dislocated themselves.”

Luchford himself, however, is as firmly ensconced within that industry as ever. While signed exclusively to Prada, he created iconic imagery alongside creative director David James – including autumn 1997’s Amber Valetta portfolio, in which the model floats in the dreamscape of a misty and mystical-looking lagoon. Luchford has also worked for Yves Saint Laurent, Calvin Klein and Levi’s, and has even been credited with inspiring Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal with his 2001 film Here to Where, the tale of a man stranded at an airport which was nominated for an award at the Edinburgh Film Festival that year.

“It comes from the multiple layers that make up one’s personality,” he says of the aesthetic he has created (which he attributes to having watched so many Seventies French films on BBC2 during the Eighties). “Coupled with 45 years of experiences that kind of vomit themselves out. I do try very hard to think things through, but normally end up winging it on set. At that point, you retreat back to pure ‘you’, I suppose.”

"I’m always influenced by someone who has get-up-and-go"

The immediacy of Luchford’s work is perhaps a by-product of his method, as much as his trajectory in the profession was unplanned and incidental. Having grown up near Brighton and left school at 15, his first job was in a hairdressing salon. “I never really thought about my career until I left school,” he remembers. “I got a job in London and got to wear swishy clothes, which seemed like a treat. Then I was invited to be an assistant to a hairdresser and wannabe photographer. I quit after that, pursued photography and got a job at The Face one year later.”

Luchford is as a blunt as he is energised; his new book is as much a comment on himself as it is on his stellar career, shot through with a percolating melancholia about times gone by and the evolution of his craft – not self-indulgence so much as self-evaluation. “The high point of my career was that first year,” he says. “I couldn’t believe I’d get paid £150 to take pictures for magazines. It felt like a fairytale. Now I’m just overpaid, fat and cynical, metaphorically more than literally. I’m always influenced by someone who has get-up-and-go,” he adds, perhaps with those deliquescent negatives in mind. “I love it, and I despise apathy and torpor. When I meet younger people who don’t know when to stop, I’m thrilled by it.”

Damaged Negatives by Glen Luchford is out in December. The book is directed and designed by DJA and published by Dashwood Books.

Text by Harriet Walker