Peter Blake’s perfectly titled semi-retrospective at Waddington Galleries Rock, Paper, Scissors neatly categorises works both old and new into the methodologies he has explored for over 60 years – sculpture, painting, assemblage/collage...

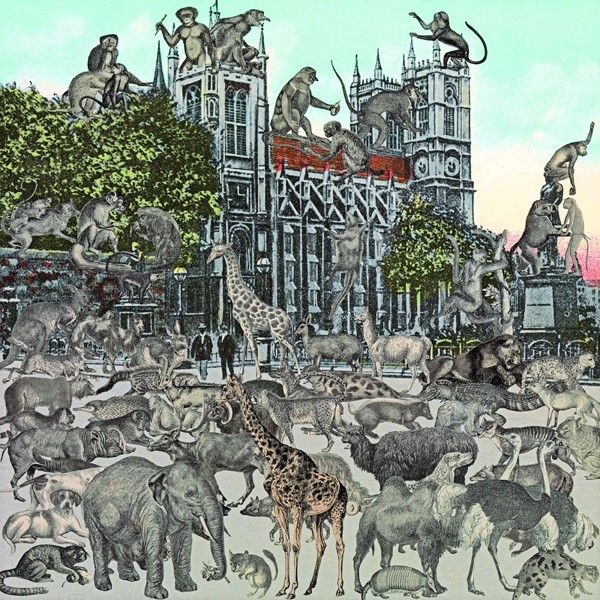

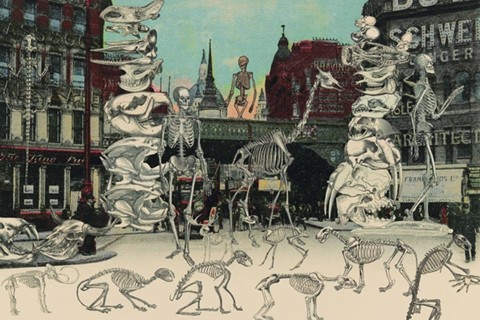

Peter Blake’s perfectly titled semi-retrospective at Waddington Custot Galleries Rock, Paper, Scissors neatly categorises works both old and new into the methodologies he has explored for over 60 years – sculpture, painting, assemblage/collage. It’s a life-affirming show from the legendary artist, featuring some wonderful new works such as ‘A Parade For Saul Steinberg’ and ‘The Surrealist Shows Snow White His Garden’ (in which a found figurine representing Magritte introduces Snow White and her diminutive entourage to a walled garden of melted comb trees and other assorted objects) alongside never seen before watercolours from the early part of his career and even an as yet unfinished work begun in 1963. It’s an extravagant, whimsical toy-filled wander into the imagination of a man as irreverent and playful at eighty years of age as he ever was, and one that reaffirms his position as one of the most effortlessly brilliant artists of our era. Here, he tells AnOther about the childhood games he played in his youth, the joys of brick-fighting and why the most seemingly innocent games are often games of fate...

The title of this show references children’s games and the childhood ephemera that plays a big role in your work – are there any games in particular that shaped you creatively as a child?

I think it's the lack of games that informed me rather than a particular game. I was seven when the Second World War started, so I don’t remember too much before the war, and the fact I was an evacuee has to come up as a powerful element in my answer. I think it was the deprivation from games that has made me use so many toys and stuff like that in my work. I only glimpsed that part of childhood, and some of my work is like little glimpses of that memory. I suppose you are aware of games from the age of about five, so I had a couple of years of it, but then five years without it. The games I can remember, though, would have been the playground games – like girls skipping, and that jumping game that you draw out on the ground: hopscotch. I came back to London as the war was ending, and I remember that we used to go brick-fighting with local gangs – I mean, they weren’t gangs like now, but gangs of kids that would go to an a bomb-site, build a camp and then throw bricks at each other. I suppose that was brick-fighting. (Laughs) I’d forgotten that completely; that we played that game. It was incredibly dangerous. We also played a kind of speedway – a bicycle speedway where we’d set up a track; and we played a kind of cycle polo in the street.

Childhood has changed profoundly since then, what would you say was different about the way children play games now?

Childhood is so different, isn’t it? You wouldn’t let your kid play outside anymore. That's gone. Innocence is gone, and kids can’t be let out to have that kind of adventure anymore. I used to live near Dartford Heath, which was an area that wasn’t quite a park, but more a kind of rough parkland and there were little woods there and there some natural ridges that we used to make bicycle tracks over. I suppose you could go and have these experiences in that bit of childhood that you just can’t do now. I imagine that a child now is much more interested in being on a computer.

"I think it was the deprivation from games that has made me use so many toys and stuff like that in my work"

There is an argument that there is a stage lacking in child development now where you have to traverse the world alone...

Well, it’s like an animal thing, isn’t it? You’re a young animal walking away from its parent and learning life – that's absolutely right, there is probably a whole area of life they are not learning about, and eventually it might be that parents won’t let kids go out at all and kids won’t even know how to go out, will they? They won’t know what it is. They’ll be taken to school in a car and they’ll be picked up; they’ll watch their videos on the computer and won't know what natural adventure is all about…

It's a right of passage that they’re lacking...

Absolutely, yes.

Do you fancy a quick game of Rock, Paper, Scissors?

Thanks, but it’s not a game I have ever really played.

You must have played it...

I know what it is, I’ve had it demonstrated to me, but somebody told me that their kids do it all the time to decide who does what. If there is a task to be done they’ll play it and the winner doesn’t have to do the task. It’s very much a current game, in that sense. It really is a game of fate, isn’t it? A lot of my work is kind of about fate, in a way, so there’s a subtext there. I’m very much aware of that continuum of past-present-future. And I think that the future probably gets a bit mixed up with the past – Saul Steinberg is gone, for example, but the drawings still exist, and if I talk about him or make a work about him, he sort of still exists.

Are you fatalistic?

I am fatalistic. It’s the same approach to life as the past, present and future. If I’m with somebody that's driving who falls asleep I don’t get frightened. I used to be frightened of the car crashing, but now I’m just not.

It just happens when it’s meant to happen…

Yeah. I just hope that it’s not yet. I was reading the other day that the oldest man alive is one-hundred-and-ten. I did think: ‘Well, that could give me another thirty years!’ I’ve been with my wife Christie thirty years, and that's a big part of my life. I’ve done an incredible amount in the last thirty years. I mean, if I have another thirty, god knows what I will do!

Rock, Paper, Scissors is currently showing at Waddington Custot Galleries until December 15.

Text by John-Paul Pryor