Glynn Griffiths taught himself photography as a school-boy in South Africa, taking to the medium like a proverbial duck. He went on to work as a sucessful photojournalist for many years...

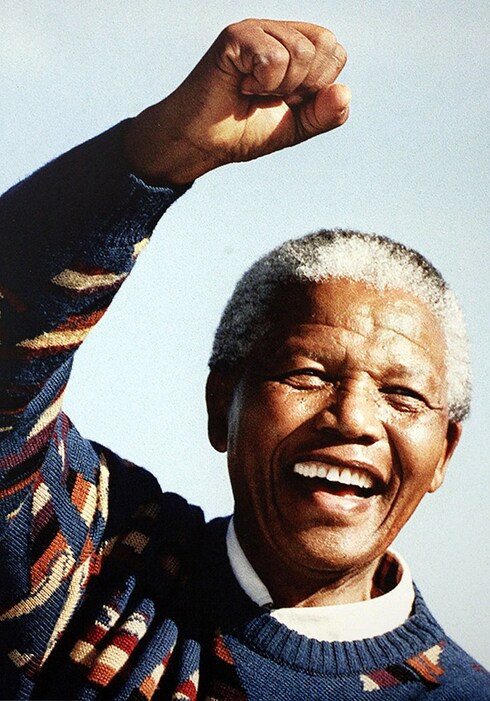

Glynn Griffiths taught himself photography as a school-boy in South Africa, taking to the medium like a proverbial duck. He went on to work as a sucessful photo-journalist for many years – first in Cape Town during 1970s apartheid, and later in London where he joined The Independent's famed team of staff photographers. During this time he returned periodically to South Africa to document the run-up to the country's first free democratic elections and took many outstanding photographs, the most memorable being a beaming Nelson Mandela at his final election rally.

But despite his considerable achievements during his career, Griffiths had a niggling desire to become a sculptor – a dream he finally fulfilled in 2010 after undertaking an MA in the medium. Now, a new exhibition at London's Horsebox Gallery celebrates both Griffiths' early days in photo-journalism and his impressive transition into sculpture. A number of the most moving images from his time in South Africa hang alongside a hand-written description of his memory of each event; while his sculptures punctuate the floor space, combining the natural and the manufactured in thought-provoking juxtapositions which remain pleasingly open to interpretation. Here, on the day of the show's opening, we speak to Griffiths about photographing Nelson Mandela and the overlap between his images and sculptures...

When did you first discover your love of photography?

I can't remember not having a camera, albeit my mother's old Kodak Box Brownie which I used to carry around taking photographs of everything. At some stage I worked out I needed film as well. Our neighbour was an ex-seaman with more tales to tell a young boy than any library could offer. He also had a darkroom – that's where I learned the magic. I grew up in 'Smalltown' South Africa. When I was about 11, I went away to boarding school and he gave me an old Halina camera.... and some film. The school had its own darkroom and I very soon became an unofficial school photographer.

You were photographing in South Africa at a very significant time, how did it feel to play a part in the documentation of that period of history? And did it have an effect on your future career?

After my compulsory National Service I worked very briefly in a camera store and then got offered a position as a trainee photographer on the Cape Times newspaper. It was a liberal newspaper with an anti-apartheid stance. As a photographer you covered everything from sport, to social functions, to riots. Later as a freelance I started to do personal projects such as photographing the "illegal" squatter camps near Cape Town. Photography by many incredibly committed people played a hugely important part in supporting the protest movement. The photographs I did during that period undoubtedly gave me credibility when showing my portfolio to newspapers when I came to Britain.

"Mandela raised his fist in the most relaxed of salutes to acknowledge the roaring crowd – his people."

Could you please recall taking your image of Nelson Mandela?

Tens of thousands of supporters filled the township stadium – all waiting to see Nelson Mandela at his final election rally in Cape Town. The full-throated "wall" of singing – calls, chants and refrains from the rich African voices rolled across you, squeezing your chest with anticipation. Without warning the gates to the stadium opened and in drove Nelson Mandela standing without ceremony in the back of a pick-up truck. His huge smile was so wide and open; he raised his fist in the most relaxed of salutes to acknowledge the roaring crowd – his people. It was truly unforgettable.

What makes a good photograph?

For every good photograph, there is a different good reason.

Do you see any overlap between your photographic work and sculptural work?

I use photography as another sketching tool. It cements ideas by forming foundations for developing ideas; both 2D and 3D. All the methods blend into some sort of physical presence.

What inspires your practice?

The good fortune that I want to do it.

What’s the best piece of creative advice you’ve ever been given?

Start with what interests you, because that'll take you to the next interest that you didn't even know was there.

Do you have a motto for life?

A few years ago I was asked to give the speech at the combined birthday party of some 21 and 18 year olds. Tricky if you don't want to sound like a pompous old fart. In the end I spoke about regret: not the regret of things you've done, because that's life and learning, but the regret of things that you haven't done. So if you're 60 and want to go to art school – do it.

Glynn Griffiths, Growth, Gravity & Balance is on display at The Horsebox Gallery until February 8.

Text by Daisy Woodward