In a brightly-lit, glass-walled office on the third floor of the Alfred Dunhill headquarters in central London, sit three of the city's most innovative and forward thinking menswear designers. Kim Jones...

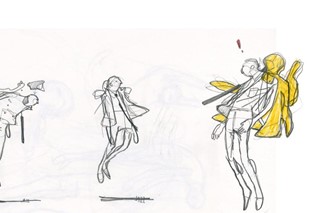

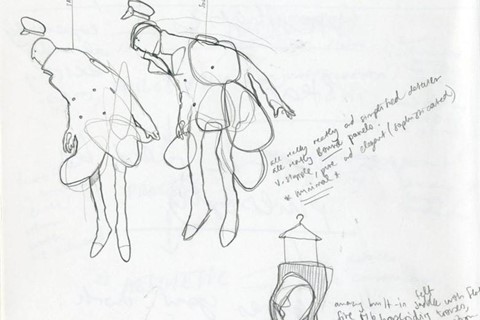

In a brightly-lit, glass-walled office on the third floor of the Alfred Dunhill headquarters in central London, sit three of the city's most innovative and forward thinking menswear designers. Kim Jones established himself during the early part of the Noughties. His considered take on youth and the attitude and masculinity of his designs earned him a deserved fanbase, further cemented by his later collaboration with the sportswear brand Umbro. In 2008 Jones joined iconic British menswear brand Alfred Dunhill as creative director, a union that garnered much praise. Sat next to Jones are Aitor Throup and Jonathan Anderson. Throup's conceptual and technological experimentation, combined with his refined aesthetic and intense interest in the functional, has earned him a cult following. The Argentina-born designer, who has worked with Stone Island and CP Company, and recently designed the England football kit for Umbro, will shortly be releasing his much anticipated debut signature collection. Jonathan Anderson is the creative director of his own line, JW Anderson, currently heralded as one of the bright lights of Britain’s new menswear talent. He is also credited with revitalising Sunspel, a company known for its fine quality men’s underwear. Dutifully appreciative of London's heritage as a hub of men’s design, the three designers represent a sharp new take on British menswear. We brought them together to discuss a changing industry, the effect of a digital marketplace, and the death of youth culture as we know it.

Do you think there has been a genuine shift in menswear trends over the last couple of years towards a more formal look?

Kim Jones: Working for a large company that has a formal element to it, I think yes, in some cases, formality is what people are buying. You have to remember that what journalists and brands project is not always held up by sales. I look at a trend in terms of the sales that are being made – and in reality the majority of guys are still buying T-shirts and jeans. I don’t think the man on the street has changed that much.

Why do you think younger, cutting-edge designers are collaborating with heritage brands at the moment?

KJ: It is so tough to be an independent now. There isn’t the freedom to just be a designer; you really have to focus on the business side of it and it’s a lot harder to be cutting edge and maintain longevity. It has always been about survival of the fittest, but I think there is less option to have that situation now because the customer wants familiarity, which is so dictated by the internet.

Jonathon Anderson: It's great to have millions of people who have online access to fashion now though. I think that is where young designers are going to get information, inspiration and feedback. You can tap into an audience quickly and get straight to the buyer. You can almost hijack the journalist. I think it would be really exciting if there were no seasons and you sold immediately from presentations or videos. The online side of fashion is part of a huge shift within industry hierarchy, which is exciting. On the other hand, stylistic references have perhaps become married together because of its global nature.

Do you think youth culture is as important to style as it was?

Aitor Throup:There is no youth culture left, is there? No one is angry anymore; kids are ultimately a lot happier because everything is so accessible online.

KJ: If you're emo, you can meet millions of other emos online straight away, and if you're gay, you can meet millions of other gay kids online straight away. You're not one kid fighting your corner anymore.

Do you think the loss of what our generation knew as youth culture, and the fact that younger people today don't have those “tribe” affiliations, has affected the way you design?

AT: When I was growing up in Burnley around football casuals, that idea of going to watch the match every Saturday and being a part of a group of like-minded individuals, wearing something that affiliated you with the people around you – that really did inspire and capture me in some way. The idea that you associated through the labels and brands that you wore – Stone Island or CP Company, for example. Ultimately we were appropriating those brands and taking them out of context, and it was that I found really interesting; we were pushing them forward. I have never found myself inspired by what is happening online.

KJ: I remember realising after going to a nightclub in Australia, based on how people were dressed, you could have been at any club in the world. There is no sense of people creating their own culture anymore; it is about following one leadership. That really is the effect of the global online community.

So what is it that you are looking to now – what do men want from their clothes?

JA: I think men are a lot more stylistically driven than they were. They are more willing to, in that clichéd way, “shop for the weekend.” They are willing to invest, to take more risks and indulge.

AT: It depends though. It’s easy to say “men” but you can't genalise like that. I go up to Burnley and, trust me, it is still full of men who aren’t willing to pay much for clothes.

JA: Yes I agree, but if you look at it on a global economic level, men are spending more on clothes than they were.

Where do you think this is taking menswear?

JA: I think that we are going to see brands pan out a lot more. The brands that will be both stable and creating something interesting and innovative will be the ones that manage to encompass many different men.

KJ: It is about tiering, having something that funds the more avant-garde or experimental designing. That is the position designers now ideally want to be in, to have a mainline that is purely their vision where they push boundaries and to have other avenues that drive the business.

AT: I think that idea is incredibly relevant, because it is not diffusion, it is simply being aware of your customer.

KJ: That is the similarity with us, perhaps, and with a lot of menswear designers in London; we all have larger brands that we work with, while at the same time continuing our own experimentation. I think that is the key, and why London especially is at the forefront of menswear. I think a commercial awareness combined with more avant-garde experimentation is what keeps London menswear really exciting.