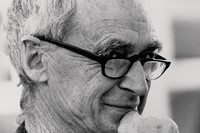

Earlier this week, visionary architect Paolo Soleri passed away at the age of 93, leaving behind a rich legacy of ideas about the way we live, and a utopian dream in the deserts of Arizona...

Earlier this week, visionary architect Paolo Soleri passed away at the age of 93, leaving behind a rich legacy of ideas about the way we live, and a utopian dream in the deserts of Arizona. There, in the sparse landscape north of Phoenix, he invited builders, architects, makers and seekers to join him in creating a new type of city – one more in tune with nature and the needs of its people. He called it Arcosanti, and over the last four decades it has served as testbed for his ideas, a home to hundreds and a magnet for those in search of a new way of life, and a glimpse at a possible tomorrow. Last year, AnOther Magazine spent a few days in the unfinished city, meeting the people who today are pushing the project forward and working to fulfil Soleri's towering ambitions.

Crickets chirp as dusk slowly settles over the high desert. Above, the stars that make up the W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia begin to emerge from the darkening sky and two owls hoot softly in the distance. The natural chorus is punctuated by the sounds of children playing and people making their way down to dinner, their voices echoing up through concrete arches, amphitheatres and apartment blocks. With no traffic, the sounds of nature and people dominate. As a vision of how we could – and should – be living, it’s pretty close to perfect.

Welcome to Arcosanti: an experimental community founded by Italian architect Paolo Soleri in 1970. In the four decades since, this small outpost on a mesa 70 miles north of Phoenix, Arizona has been home (at various times) to over 7,000 people. A mixture of do-ers, dreamers and seekers, they’ve all come to help create a new type of city: one in which we live closer together, more socially, and surrounded by nature. It’s a living prototype for what Soleri calls ‘arcology’ (architecture + ecology) – an urban blueprint designed to eliminate traffic and sprawl while preserving the surrounding environment. “What is needed”, wrote Soleri, “is not a Disneylike simulation or an arcadia but a movement into the complex, self-clustering, environmentally coherent towns and cities we could invent if we put ourselves to it.” The idea was one of “urban implosion rather than explosion”.

"With no traffic, the sounds of nature and people dominate. As a vision of how we could – and should – be living, it’s pretty close to perfect"

“This isn’t the answer, and it isn’t the only answer,” admits David Tollas, construction manager at Arcosanti. “If everyone started building arcologies everywhere, it wouldn’t solve a lot of the problems we face. I think the important thing about this place is that it’s symbolic. You can come and put some energy into something new and try it. I think that’s its value – it’s a place to contribute”.

The DIY spirit and hands-on nature of the project mean that such contributions come in waves. In the early days of the project, an extra camp was needed to house all the volunteers who flocked to the nascent utopia in the desert, building the vast arches, a swimming pool and housing for 100 residents. These days the 60-odd residents are joined by a small but steady trickle of architecture fans and students who come to take part in five-week workshops, giving them the chance to experience life here first-hand while adding incrementally to the site. It is also host to a steady stream of visitors, with 35,000 tourists a year making their way to the site – tours take place daily.

It’s a slow process, and no major buildings have been completed since 1989. But while grand visions of a city for 5,000 seem more distant than ever, there is a sense that something is stirring on the mesa. At 93, Soleri recently retired from actively managing the project, though still visits regularly. There’s an energetic young CEO and a new greenhouse complex under construction, something that could give Arcosanti a bit more self-sufficiency. Nadia Begin, one of the city’s key planners, sees echoes of the 1970s in today’s world.

“There is a similarity to back then,” she explains. “It was after the Vietnam war and people didn’t like what was happening politically and wanted to do something differently – there was a surge of ‘we have to do something about it.’ Now it’s a different time but I think there’s a similar surge; things are falling apart, and we’ve created a system that’s not working.”

A fresh infusion of volunteers and new residents could be just what the project needs. While massively impressive for the fact it literally exists (literally in concrete form) in this age of unrealised CGI dreams, Arcosanti seems oddly out of touch with current sustainable ideals – with only a handful of solar panels, for instance, when the city’s desert location could make it a carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative settlement. Nearly all the food is shipped in, meanwhile, something the new greenhouses could help address while also fostering a greater sense of community and shared purpose. Driven by such concerns, Arcosanti may be on the verge of transitioning from an idealised utopia to a more practical, livable one.

But part of Arcosanti’s charm is its evolving nature. “It’s the universal question: when will Arcosanti be finished?” David says. “For us, it

is finished, because we’re living here.”

This article features in the S/S13 issue of Another Magazine on sale now. Click here for more information on Arcosanti.

Text by Chris Hatherill