William Oliver talks to three creatives about the importance of art fairs

William Oliver travelled to Art Basel Miami Beach (in an attempt) to bring together three of the fair's regulars and long-time friends – Javier Peres, owner of L.A and Berlin based gallery Peres Projects; AA Bronson, one time member of revolutionary art collective General Idea and the driving force behind artists' book initiative Printed Matter; and the ever-glamorous artist Terence Koh. We discussed the importance of fairs and their critical impact on the contemporary art landscape.

Did you get the message from Terence?

Javier Peres: He’s ‘held up;’ I think he had a late one last night (laughs).

AA Bronson: Every night in Miami is a late night for Terence. Let’s do the conversation anyway, as if he was here.

JP: We can answer for him; lets imagine what he would have said.

AA: I like that. That’s perhaps how he would’ve wanted it anyway, to attend in spirit.

Then I’ll start – what’s the difference between curated exhibitions and commercial art fairs, and do art fairs have a critical relevance?

JP: Obviously, as an art dealer you cannot remove the financial from your long-term objective for an artist. They go hand-in-hand. But I try to do solo projects as much as possible at art fairs, even though they’re often less lucrative.

AA, what you do at fairs is very different to Javier. Do you curate your booth?

AA: We have done in the past, we didn’t this year. Printed Matter is a different kind of organisation; we are mostly trying to represent artists’ books. In Miami, where no one is interested in books, that becomes difficult. Art Basel in Switzerland is a very different fair because every major international curator, museum director, critic and dealer passes through. It’s a very knowledgeable audience in Basel.

JP: Miami feels like a much less intellectual fair, but I don’t know if that’s just our perception of Miami in general. It’s not to say that the big buying power isn’t here.

Is the social side of it more of an important part of this particular fair?

AA: A lot of what is important about fairs is hearing news of upcoming shows and projects but I don’t think it’s the same as it used to be. Art fairs through the 70s and early 80s really transformed the art world. For example, I feel the promotion of photography as a recognised art form really happened because of Art Basel. They created a photography section in the late 70s, and within five years the prices had shot up. Suddenly all the standards around photography had shifted and I put it down to that one little section at the Basel fair. I don’t see the fairs today having that very profound effect on the art world. They’ve become more like shopping malls.

JP: Interestingly, looking at sales in the art market, it’s the big brand artists that are doing well; they’re sustaining the market now. Five or six years ago it was more about how young an artist was, how inexpensive: now people don’t want to spend just $400 on a drawing.

AA: So you don’t think there is a low-end niche art market? Maybe self-publishing has filled that position?

JP: Maybe. Collecting ‘zines etc is about buying things because you love them; it’s not really an investment. Maybe I am being really ‘fuck you’ about the art world, but I do feel like people aren’t as excited about new art as they used to be.

AA: One thing that is worrying me is how schools have been transformed by the market place. Certain schools have become a real entrée to the market, the right dealers and the right curators. I really don’t like that.

JP: It’s quite like that at the moment in NY and LA. If you go to UCLA you know you’re going to show at something; it’s almost on the curriculum.

AA: It was fascinating to me watching crits at Yale. They’re held in a ‘White Cube’ style gallery space and during the first hour the artist doesn’t speak while the rest of the class discusses what the work was saying, what it was doing with the ‘non-contextual’ space around it. That in itself is a very market orientated way of looking at art. I find it peculiar to see it happening in an art school. The curriculum for Columbia guarantee’s that ‘important people’ will come to see your work.

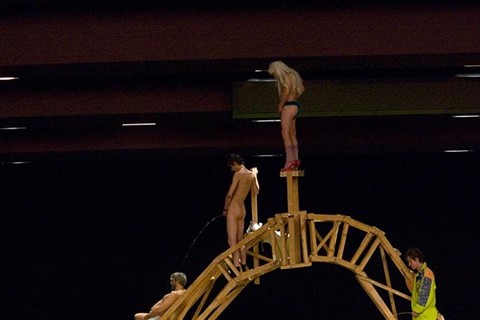

JP: Ultimately, it’s important for the commercial aspect to be part of the curriculum, but it shouldn’t be the main aspect. It seems like some colleges are pushing their students to make work that fits into a ‘white cube’ space, or fits into an ArtForum ad. Art can be commodified, but in itself, art s not a commodity. I’ve been really interested in performance recently, which is really hard to package and commodify. There was an amazing piece recently in Turin, Italy, by the group Gelatin, as part of Artissima. It was performed in a beautifully designed old theartre to an upper middle class, almost aristocratic audience, and it ended with performers all pissing on each other in formation.

AA: I’m really interested in what performance art is doing at the moment, I’m really excited by the performance Jacques Vidal and Justin Liebe are doing here. The most interesting artists to me are those who are very difficult to commodify because the art they make, and the lives they lead, are difficult to separate, which is often the case with performance artists. For instance, with Terence himself, he is very much about the bigger picture; his work is almost the residue or the detritus of the life he is leading.

JP: Talking of Terence, what did he have to say about all this?

William Oliver writes for Another, AnotherMan and Dazed & Confused and recently contributed to exhibition catalogues for Adam Neate’s show, A New Understanding and Rankin's Cheeky book of erotica photography