In the wake of the El Bulli exhibition opening at Somerset House, we catch up with already legendary cook Ferran Adrià, to discuss food, art, innovation and his 27-year rule at the restaurant.

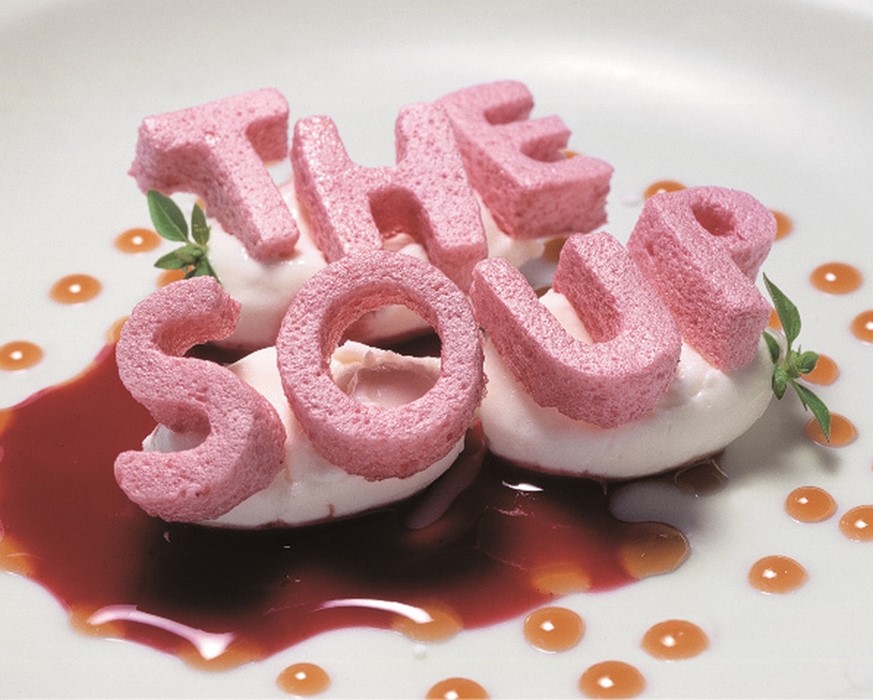

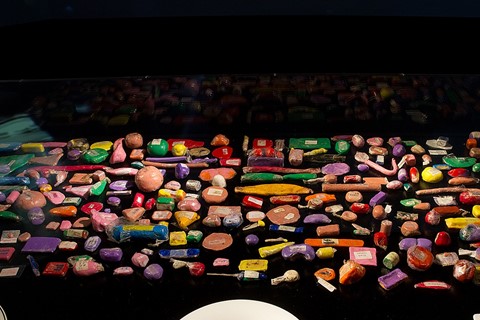

Olive oil caviar, pine cone mousse, asparagus beer: these are only three of the 1846 dishes Ferran Adrià created during his 27 years at the front of El Bulli. The three Michelin-star restaurant, located at the Cala Montjoi in Catalonia and known for its outrageously avant-garde cuisine, was the best in the world for most of last decade. So it came as a shock when, in 2011, it closed down. Or, rather, started a transformation. Today, 51 year-old Adrià juggles between several revolutionary projects while still finding time to participate in Somerset House’s latest exhibition, a behind-the-scenes look at El Bulli’s laboratory and kitchen. AnOther caught up with the already legendary cook (he refuses to label himself as a chef) to discuss food, art, and innovation.

How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

We closed the restaurant in 2011 ago and we’ll launch our next project, El Bulli Foundation, in 2015, so this felt like a good time to do a retrospective. We wanted to celebrate the creativity, innovative spirit, talent and teamwork of everyone who worked at El Bulli over the years, and especially the world-famous chefs who trained with us and later took these values into their own restaurants around the world. The exhibition is conceived so that people will understand the history of El Bulli from its beginnings as a beach bar in 1962 to its international notoriety during the 1990s and its evolution towards a thoroughly cutting-edge venture in recent years.

Where does your creativity stem from, and what has mostly inspired your work?

French cuisine influenced me enormously during my formative years, and it still does. I learned everything I know from El Practico, a book about the basic rules of haute cuisine written in the 1920s by Ramon Rabaso, a Spanish chef who worked in Paris during the Belle Epoque. Later on, as I started travelling abroad, I brought something back from each country I visited: Peruvian, Japanese and Chinese culinary traditions inspire me especially, although lately I’m getting more and more into London and its mix of traditional British cuisine and cosmopolitan spirit. In fact, I’m planning to stay here all throughout August to search for new ideas to adapt, deconstruct and reinvent. I see my job as a blend between cheerful play and bold experimenting. I couldn’t imagine working any other way.

Does the natural landscape of the Cala Montjoi, where El Bulli is located, have an influence in your outlook and your cuisine?

Definitely, it always has. I think it’s inevitable to see the world through the prism of one’s roots, and I have been lucky enough to live all my life in the Ampurdan, an exceptionally creative area thanks to its beautiful light and its joyful people. It was Salvador Dali’s native region, and both Picasso and Miro lived there for years. It’s the Ampurdan’s energy and emotion that have inspired me, more than its cuisine or its local products.

Your molecular cuisine has often been compared to surrealism, and the Somerset House exhibition is precisely titled “The Art of Food”. Is food really an art form?

When the New York Times first published an article about El Bulli, they compared me to Dali. That was really flattering… But I’m a cook, and I’m well aware of my limitations. I admire the work of artists but I don’t aspire to practice their art. Whether cuisine is an art form or not doesn’t interest me. What I find fascinating is the dialogue between both disciplines: my dishes, for instance, have nothing to do with art. But, like an artist, I seek to move people through them. Above anything else, I’ve always wanted to make people happy with my work, and I think at El Bulli we succeeded in doing that. Food has an incredible power to create happiness.

"To us, El Bulli is not just a restaurant, but a way to understand food and life, and that will go on in a different form"

Spain is currently living its own golden age of gastronomy, with some of the best restaurants in the world and some of its best chefs working abroad. How would you explain this?

Spain is a very non-conformist country. We may not have many economic resources, especially in these last few recession years, but we generate a lot of talent with what we have. Coincidence has also played a part, and during this last decade a group of gifted, savvy, thoroughly modern young cooks has stood out. Joan Roca, who used to work at El Bulli, went on to build El Celler de Can Roca, today considered the best restaurant in the world. Others, like José Andrés and Dani Garcia (who has just opened Manzanilla Spanish Brasserie, an Andalusian restaurant in the heart of New York City), have moved to the United States and received rave reviews. Thanks to them, and to gastronomy, Spain has become a truly avant-garde country in the eyes of the world.

Why did you decide to close the restaurant at the height of its success?

Towards the end of its existence as a restaurant, El Bulli was becoming a media phenomenon so huge we could no longer control it. Every year we received two million calls of people wanting to book tables when we could only accommodate eight thousand clients. The situation was almost violent and we weren’t happy about it. What’s more, my team had already asked me for a change in the way we were running things: our day-to-day life was becoming monotonous and predicable, and that’s a true creativity killer. However, the place never really closed; it is simply being transformed into something else. To us, El Bulli is not just a restaurant, but a way to understand food and life, and that will go on in a different form.

What is El Bulli Foundation and how will it work once it’s launched?

El Bulli Foundation is a venture combining cuisine and innovation that I’ve been able to develop with the help of a group of students from six top business schools. It gathers three different projects. The first one, El Bulli 1846, will be a museum about the history of cuisine. Bullipedia will be an interactive encyclopaedia tracking the greatest developments in gastronomy. And I will get back to the kitchen with El Bulli DNA, a research centre where I will continue to experiment with food, broadcasting the results through Internet. It will launch in March 2015 and will include a restaurant open for one month every year.

Rumours are Hollywood is producing a movie about El Bulli. Is that true?

Yes! Lisa Abend, the New York Times Spain correspondent, stayed at the restaurant for one year and wrote The Sorcerer’s Apprentices, a book about the (hard) lives of El Bulli’s interns. I found it so brilliant I passed it on to producer Jeff Kleeman in 2011. We’ve been talking for two years and the film is now in pre-production. No directors or actors have yet been signed up, but once they do I will open the restaurant to train them in the ways of El Bulli and to act as a technical advisor. The movie will be a tribute to all the hard-working interns around the world, I expect it to be something between The Social Network and Ratatouille.

El Bulli: Ferran Adrià and The Art of Food is at Somerset House until September 29 2013.

Text by Marta Represa

Marta Represa is a freelance writer specialising in fashion, art, photography and culture.