AnOther speaks to Nottingham Contemporary's director Alex Farquharson about their latest exhibition, Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep

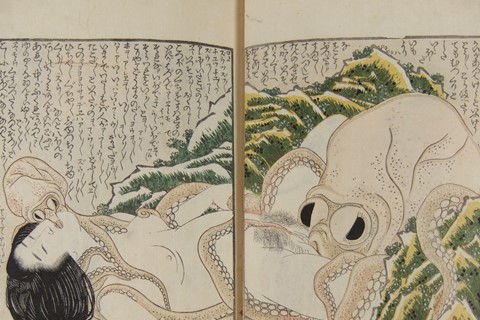

The sea has been a source of both fascination and fear since time began, stirring myths and legends and providing the setting for some of art and literature’s most enduring images and tales. From classics such as The Odyssey, Moby Dick and The Little Mermaid, to the sci-fi-tinged Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and even pulp extravaganzas like the recent B-movie Sharknado, the sea and its beasts mesmerise and repel us in equal measures. Nottingham Contemporary’s exhibition Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep, explores this duality in works of art spanning history, ranging from atmospheric seascapes by JMW Turner to video work by the experimental Otolith Group. AnOther spoke to Nottingham Contemporary’s Director Alex Farquharson, who curated the show, about the ideas behind the exhibition and its alluring imagery.

I’m struck by the title of the show, and the idea of the sea as an unknowable, potentially utopian space. Could you explain the title?

Hopefully the title implies both utopia and dystopia. Often, the sea represents both to us, and sometimes at the same time, something I think that’s evident in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. In terms of actually naming the show, I’m indebted to Kodwo Eshun of the Otolith Group, who gave an amazing lecture on Drexciya, the electronic duo, who kind of referred to what he called an “aquatopian” genealogy in popular music. It somehow stuck as a name for our exhibition, the difference being that we’re applying it to the visual arts and sometimes via literature.

"The sea represents a space of otherness, a space of the unconscious or sub-conscious, a dream space where things are distorted"

I was wondering actually if there was a particular story from literature that inspired the exhibition?

Well I would say that they all do, going back to the Greeks or pagan beliefs. What crystallised it for me was Kodwo’s account of the Drexciya [a myth dating back to slavery, wherein pregnant slaves thrown overboard during the Middle Passage adapted to sea life, forging a sort of black Atlantis]. It’s familiar to a lot of western sub-aquatic myths, Atlantis for example, where the sunken city is a kind of aqua-Utopia, but in this case has a very powerful link to the trauma of the Middle Passage. It replays a lot of those western European archetypes as a kind of black power or almost black superhero – an avenging myth built around the Middle Passage. It made me think that there could be a number of quite hard-edged and modern versions of these myths laid out in a number of contemporary artworks, others perhaps being more feminist or queer in orientation. That was important from the point of view of not wanting to make an exhibition that was purely fantastical and escapist; that these myths could be a way of narrating quite challenging things in culture and politics.

What draws you personally to the sea?

I tend to assume everyone is, I don’t know if I’m any different. If one lives by the sea, the oceanic is going to be very important, but I think that to everybody the ocean is this space of “otherness” really. But it’s not in the universe somewhere, it’s on our planet, and actually although we think we designed the planet and in terms of geology we define it through the land, in fact the sea accounts for a lot more of the planet’s surface. I think it was Arthur C. Clarke who said the Earth should really be called the Sea. We can’t exist in it, and so it’s both kind of frightening and fascinating. We can’t exist underwater unless we’re aided almost like a spaceman and I think for us the sea represents a space of otherness, a space of the unconscious or sub-conscious, a dream space where things are distorted, where we have almost a fun house mirror version of our land-based lives. Think about the kind of flora and fauna of tropical reefs; and then the darker depths, a space where there is finally no light at all from the sun, and what light there is comes from very strange animals. Or think of the ocean floor, which for sailors and our species in general, represents death.

"It’s like Björk's undergoing metamorphosis and becoming squid herself, as if her innards are squid entrails, and instead of red blood she had black ink"

One of the works I particularly love is Juergen Teller’s photo of Björk with the squid ink pasta coming out of her mouth. I was wondering if you could talk about this image a bit?

Juergen’s photography is quite unique in the way that he sets up these very playful relationships with the subjects of his photographs, and that results in a photography that is very close to performance art sometimes. What I really like about that image is that it’s almost bestial, kind of metamorphic; it’s like she’s undergoing metamorphosis and becoming squid herself, as if her innards are squid entrails, and instead of red blood she had black ink. It’s like her very being is emerging from her mouth and the black ink contrasts brilliantly with her black hair, which is flecked with squid ink. She’s a woman becoming squid, which, if one thinks of mermaids, Tritons and so on, is a common idea within sea mythology. The Drexciyans are mermaids of a sort, too. We’ve inherited sentimental versions of the mermaid, but historically and in folklore a mermaid was a much more frightening thing that could threaten lives. In the exhibition we’ve juxtaposed new works with historic works throughout and this particular image sits next to a beautiful, very tiny Lucian Freud painting of a squid that looks like an odd, misshaped human nude and it’s also leaking its black ink – so there are these little correlations throughout. With the Otolith Group’s film, there’s a moment where it focuses in on a famous painting by Turner of the stow ship and the pregnant women being thrown overboard – the famous incident that their film is partly based on. That painting is in Boston and immovable but instead we’re showing what looks to me like a very futuristic painting by Turner of a sea monster at sunset, and it kind of looks like a 19th century Jules Verne submarine rising to the top of the ocean in a misty sunset.

The show is moving to St. Ives next month. I was wondering if you think it will take on a new lease of life closer to the sea?

I think the exhibition will have a really different feel and will appear much more site-specific. Half of the building faces the ocean, which is just a few metres away and you hear it as you’re entering the building. I think the exhibition will really speak to it, especially the big sound piece Sea Women [about women divers from an island off Korea] by Mikhail Karikis. There will be sound both within and outside the building – it’s quite loud and it will speak directly to the sea. I think the way it is installed and its relationship to that place will be different and I really like the fact with Nottingham and St. Ives, one is a really oceanic place and the other is not at all. Both of those things are important to the show because it emphasizes that this is about the history of how we’ve imagined the ocean, that those imaginings themselves have a history and that they are probably more potent and ironically more real to us than the physical reality of the ocean, which is still, particularly at any depth, relatively very inaccessible to us.

Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep is open until September 22 at Nottingham Contemporary; it will then travel to Tate St. Ives and re-open on the 12th October.

Text by Laura Allsop