Simon Menner's extraordinary photographic documentation one of history’s most effective surveillance apparatuses of all time, the Stasi

From Edward Snowden's whistleblowing on the US surveillance programme earlier in the year to last week's speech by the new director general of MI5 hammering home the importance of state surveillance in the battle against Islamist terrorists, the matter of governments’ spying on their populace is a hotbed of current contention. In the midst of this furore comes Top Secret, a well-timed, newly published book by Simon Menner offering a fascinating perspective on one of history’s most effective surveillance apparatuses of all time: The German Democratic Republic’s Ministry for State Security, AKA the Stasi.

The Berlin-based photographer has a longstanding fascination with surveillance, frequently dealing with the subject in his own work. During his extensive research, he came to the conclusion that, aside from blurred CCTV footage publicised by police in their attempt to identify criminals, there is very little material detailing “what the Orwellian Big Brother gets to see when he is watching us.” Situated as he was within the German capital, Menner soon realised he was sitting on an untapped well of information, the majority of the Stasi archives having been opened to the public shortly after the reunification of Germany. Gaining access to the vast visual legacy was relatively simple, but Menner couldn’t have anticipated the quantity and breadth of the material available and it took him two years to sift through it in its entirety and extract its most intriguing photographic specimens for the book.

"They concern photographic records of the repression exerted by the state to subdue its own citizens" — Simon Menner

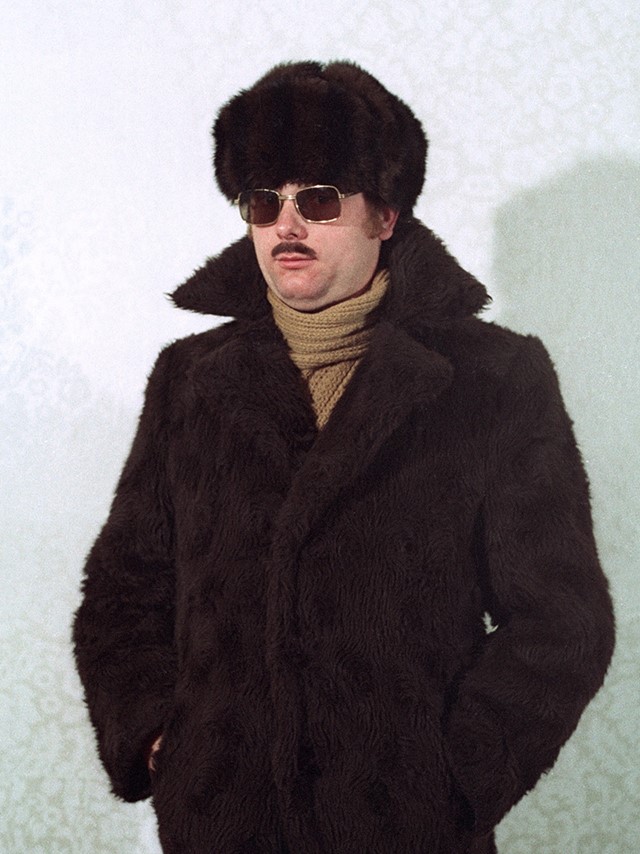

From images of Stasi members awkwardly decked in fur coats, shades and 70s casual wear in a guide to disguises, to pictures of the group dressed as dancers and church officials at a costume party in honour of a high-ranking functionary, many of Top Secret’s offerings appear absurd and amusing at first glance. But, as Menner is keen to point out, one mustn’t lose sight of the original intentions behind the works. “They concern photographic records of the repression exerted by the state to subdue its own citizens,” he expounds in the book’s introduction. Other more sinister images are chilling reminders of this, like those taken during Stasi agents’ clandestine searches of citizens’ homes. Here, something as mundane as a Siemens coffee maker (a West German consumer product), could mean years in prison for the owner, depending on how the Stasi interpreted it. While it may have simply been a present from relatives, it could equally be deemed as evidence of contact with Western agents. All in all, Top Secret is a fascinating read, remarkable for its documentation of the rarely-seen faces behind the Stasi operations, as well as a relevant comment on surveillance generally and its inherent flaws.

Top Secret by Simon Menner is published by Hatje Cantz and is available now.

Text by Daisy Woodward