A new work provides a fascinating vignette of the artistic and romantic relationship between playwright Joe Orton and his lover, and eventual murderer, Kenneth Halliwell

It is inevitable that the relationship between playwright Joe Orton and his older lover Kenneth Halliwell is seen through the prism of their violent deaths – Orton hammered to death by Halliwell, who then drank a lethal cocktail of grapefruit juice and pentobarbital. But a new book by Ilsa Colsell, Malicious Damage, is taking a step back from the couple’s tragic and violent demise, and the brief but vivid writing success enjoyed by Orton in the five years beforehand. Instead Colsell explores the three-year period the pair spent in artistic chicanery, stealing books from Islington Library.

"Between 1959 and 1962, Orton and Halliwell secretly removed thousands of books from the library"

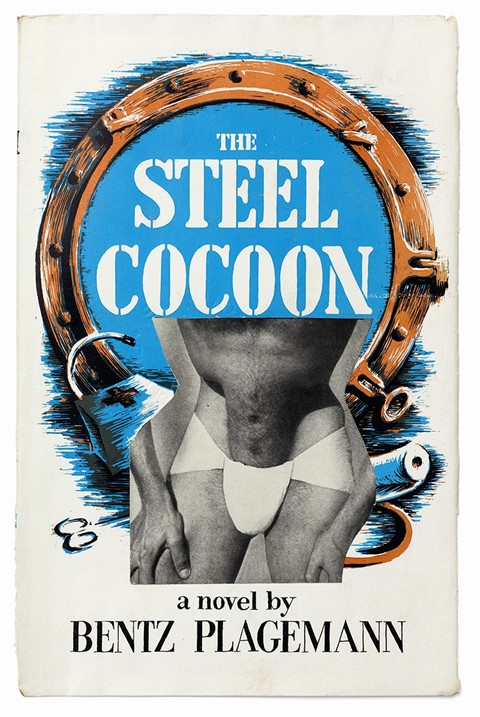

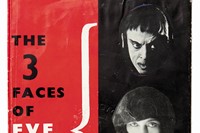

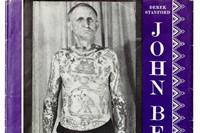

An extraordinarily creative, if criminal, undertaking, between 1959 and 1962, Orton and Halliwell secretly removed thousands of books from the library. Many had their covers reconfigured – a book of Betjeman poems was enlivened with a naked, tattooed man and a new blurb for Dorothy L. Sayers’ Gaudy Night promised “queer and crude” antics for Lord Peter Wimsey at an “infamous transvestite den” – before they were slipped back on the shelves. Others were stripped of their artist plates, with the stolen pictures being stitched together to create a densely packed collage on the walls of Orton and Halliwell’s Noel Street abode. The pair were eventually caught and sent to jail for “malicious damage”, a six-month separation that, despite their reunion and cohabitation, set them on very different paths: Orton towards fame and success, Halliwell on a downwards spiral of depression and drug dependency. But in considering this highly productive and companionable period, Colsell argues for a kinder and closer look at the work of Halliwell, so long dismissed as Orton’s petty, jealous lover, a failure riding on the coattails of his younger partner’s talent and success. Within the walls of the small Noel Street flat, Colsell provides an intense depiction of a unique relationship, as well as a wider consideration of artists and homosexuality in Sixties London. Here, she talks to AnOther about the inception of the project and what she understands to have been the purpose of Orton and Halliwell's focused desecration/creation.

What inspired you to write this book?

In 2009, I went to the Islington Local History Centre to view the collages. I have an obsession with collage and with the severed edge, and after seeing them I just kept wanting to return. Making the book became a way of returning to them daily, and researching Orton and Halliwell became a way of getting further inside the works.

What interested you most about the relationship between Orton and Halliwell?

Like most people I first knew of Orton, Halliwell being just a vague, shadowy figure standing behind him. But looking primarily at their earlier lives together brought them on to more of a level playing field. And what interests me most about their relationship now is the structure of their collaboration – that these book cover collages, their other shared writing and making, came out of a sense of continuous exchange. This really animates my imagination of the small room they shared; an intense environment of action and creative possibility.

Do you think they defaced/altered/worked with the covers of the library books purely out of a sense of artistic endeavour or was their main aim to rebel against authority?

I think both. Collage is an act of making that uses existing imagery and their attendant connotations to make comment on or an incision within a subject. It’s both a considered action of creativity and of destruction in the same moment. Rebelling against authority by first destroying it's offerings and then making anew within the ruins feels like the perfect agency of art.

What is your favourite of the alterations?

I get a huge amount from all the covers but I am most drawn to the more abstract Shakespeare covers like Titus Andronicus, Timon of Athens as well as Steel Cocoon which feels as if I could encounter that today in any good group show of collage – there is still a real immediacy in that cover that feels surprising contemporary.

Tell us about the collage they created in their flat?

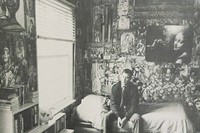

The police photographs taken in their flat in Noel Road in 1962 alongside later press photographs of the newly famous Orton, show a series of incredible snapshots within the life of this developing room of collage. Initially accumulated from the cuttings of large-scale art books, (evidently stolen from varied Islington libraries and added to while they made their altered book covers and beyond) the collage on the walls seen in 1962 is a dense mass of imagery. It can be read as their artists studio, and as a wall with which to surround and enclose their further creative pursuits. Despite it’s seemingly cosseting aspect, this room is by no means static and two years later it is further added to with larger posters and magazine paper repetitions which develop layering and depth that build to a more opaque reading. But it is after this point that we see the collage recede. In later photographs it becomes neatly bordered in around their beds or within frames hung soberly on the walls. By the time they died there was no collage pasted directly to the surface. Instead Halliwell’s solo works made for his exhibition at the beginning of 1967 and Orton’s play posters now surround them. It’s tempting to think of this dwindling collage as a metaphor for the breaking down of their shared creative relationship – but in reality we all change the spaces around us and it's reasonable to think Orton and Halliwell might have done this too.

This marks the precursor to a prison sentence, Orton's growing fame as a playwright and then, of course, the couple's tragic deaths. How – if at all – do you think this time in their lives affected what was to come?

Yes, prison has become a popular punctuation mark in their story, but it did come at a time when their relationship was already ten years in and with another five years to go before Halliwell’s final breakdown. They had largely been writing separately before this forced separation, and as Orton said he got ‘detachment’ while in prison, but I don’t see this as entirely relating to his relationship with Halliwell – more from society itself. He sees it in all its corrupt splendor, its machinations and its subsequent punishment on any transgressor of its laws – it's this that gives him his clarity. On the other hand, it’s difficult to know precisely what effect this time had on Halliwell as there are few recorded sources giving his feelings at the time (or after) but it would seem that his mental health is more clearly in decline in the following years – whether it was a direct result of the sentence is hard to say.

It is sadly unequivocal that Halliwell’s final descent pushed them both to their tragically sad end. Prison might have pushed an already delicate psyche but in this case, if it did, it was a slow burn. On a broader note, having had our society's version of ‘freedom’ taken from you, it might indeed spur you to make better use of your liberties and to push harder at the lines where these are defined. As Orton regularly described in his later diaries, there was a particularly vivid kind of freedom to be found within these peripheries.

Malicious Damage is out now, published by Donlon Books.

Text by Tish Wrigley