While talking about his iBook A New York Minute, Stephen Shore looks back on a New York lifetime

During his 50-year career, Stephen Shore has gone from wunderkind, through pioneer, all the way to American classic. The New York born-and-bred photographer sold his first image aged 14 to none other than Edward Steichen and went on to document Andy Warhol’s factory at 17, before deciding to take a road trip to Amarillo, Texas in 1972, which would inspire him to use colour in his photographs (something unheard-of in fine art photography until then). 40 years later, Shore is still seeking challenges: he has just released A New York Minute, a moving image iBook that captures the Big Apple as only Shore sees it. The photographer is also holding his first solo show in London in over six years at the Sprüth Magers gallery. Titled Something + Nothing, it showcases some of his classic Americana imagery next to his new projects shot in Ukraine, Abu Dhabi and Israel. AnOther caught up with the prolific New Yorker to discuss American photography, innovation and the Silver Sixties.

A New York Minute is quite a unique concept, how did it come about?

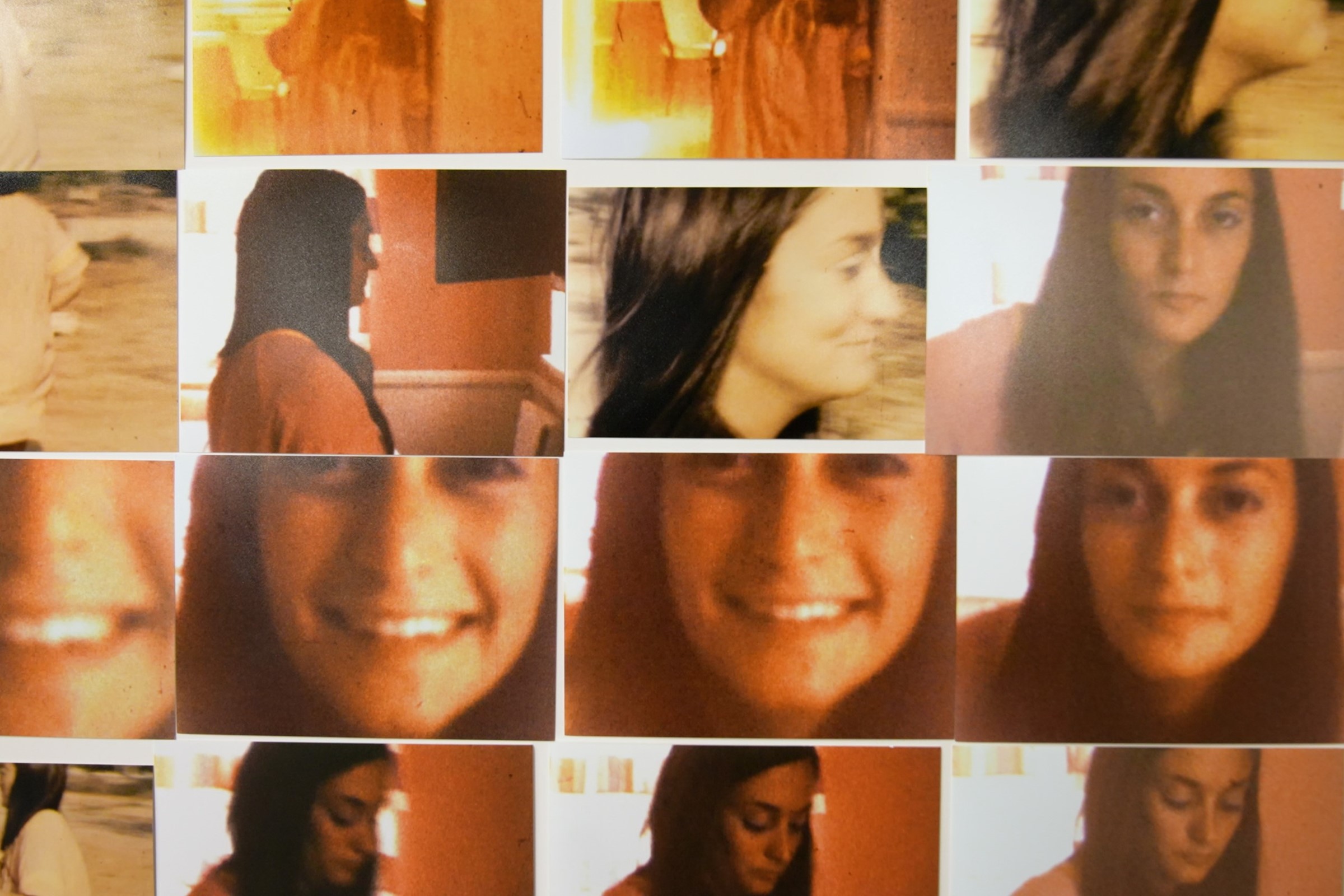

For the last few years I had been consistently reading and looking at photography books on my iPad, which made me realize most e-books are simply electronic versions of traditional publications, whereas newspapers are now taking full advantage of the new media in a much more modern way, mainly by inserting short videos in their articles. I thought I’d like to try something like that with a photography book. I chose a very conservative layout to work with – all the pictures are in the middle of the page, surrounded by white frames – but instead of still images, I shot moving pictures.

With this book you are pioneering digital photography, but 40 years ago you were already pioneering the use of colour. How important is technical innovation in your work?

I’m not interested in innovation for its own sake, but I do love a challenge and to take advantage of technological advances. I saw a great opportunity in digital books when they first started appearing back in 2002, and I spent the next five years investigating them. Around the same time, I began working digitally: a lot of my work in the past four years has been done using a very high-end digital camera, and its results are very different to anything I had got before. I get the resolution and tonality of a large-format camera while taking small-format pictures. So you see, looking at technological advances can open new possibilities.

"I think images can communicate emotions, but in my case they do it best through details"

Your pictures are technically innovative, yet their themes are mainly typically American. What American photographers have influenced you the most?

Walker Evans has had an enormous impact in my work. It’s funny, I recognise a similarity in temperament between him and me… Even if I never met him personally, visually I clearly see a temperamental connection. Several things fascinate me about Evans’s work: his exploration of the world, which runs parallel to that of the medium; the self-consciousness of his photographs as works of art; his awareness of the emotional and psychological prevalence of his images, and of the cultural implications of his visual style…

From the 1970s you became known for documenting America in a unique way – photographing landscapes and facts rather than humans. Do details express more about the American reality than emotions?

I have never figured out how someone can photograph emotions. I think images can communicate emotions, but in my case they do it best through details. As for my decision to seldom photograph humans, part of it was technical. My exposures were typically a half or a quarter of a second, so if I had a person in the shot they had to be either posing for me or stopped at a crosswalk. But I don’t want to say that it was simply technical, because I chose the tools. If having the streets full of people was that important to me and was an essential part of what I was trying to do and I couldn’t have accomplished it with those tools, I would have used different tools. There’s also another factor that those of us who grew up in New York might not recognize. If you go to some intersection in Ashland, Wisconsin, and set up a camera, if you wanted a person in the picture, you’d have to wait. In most of these towns, the streets are not full of people the way they are outside our windows in New York.

Your training took place at Andy Warhol’s Factory, where you started hanging out when you were only seventeen. What attracted you to Warhol’s crowd?

I had heard about the wonderful things that were going on with Andy, so I just decided to look him up. It was that simple. And in only a few days, those people had become my friends! At the time I liked it simply because it was fun being there, but looking back I realize I learned a couple of things from it. I know people’s perception of the Factory is that it was all sex, drugs and partying, but Andy worked every day, so I got to see an artist making decisions. He was not trying to teach me – or anyone else – anything, but he involved his friends in his work, and that allowed the rest of us, in a way, to have access to his thought process. So I came away realizing that a big part of the creative process is about making decisions.

"Andy Warhol was not trying to teach me...anything, but he involved his friends in his work, and that allowed us to have access to his thought process"

Have you any images from that time that you’re especially proud of?

There’s a picture of Andy in a Chinese restaurant at about two in the morning. I like it because it’s so normal, so unlike what people think the Factory was about. Every night we would go to parties or Velvet Underground gigs and we would put on a performance, but then we wound up in Chinatown or Little Italy to have a really normal supper.

Has New York lost the grit it had in those days?

New York has changed so much and in so many ways since the late sixties. Soho has become quite expensive so obviously it has been totally transfigured, but I think the grit still exists in some parts of Brooklyn and Queens.

Since 2010 you have been working a lot less in America and a lot more in Abu Dhabi, Israel or Ukraine. What inspired you to travel abroad?

The challenge of it. I had already done a project in Mexico in 1991, and another one in Italy two years later, but I still wanted to document different realities. The contrast was fascinating, even though I looked for the essence of all those places in pretty much the same way I have always worked back home. My next book, which will come out in the Spring, will actually be a compilation of the photographs I took in Israel.

A New York Minute is available on iTunes.

Text by Marta Represa