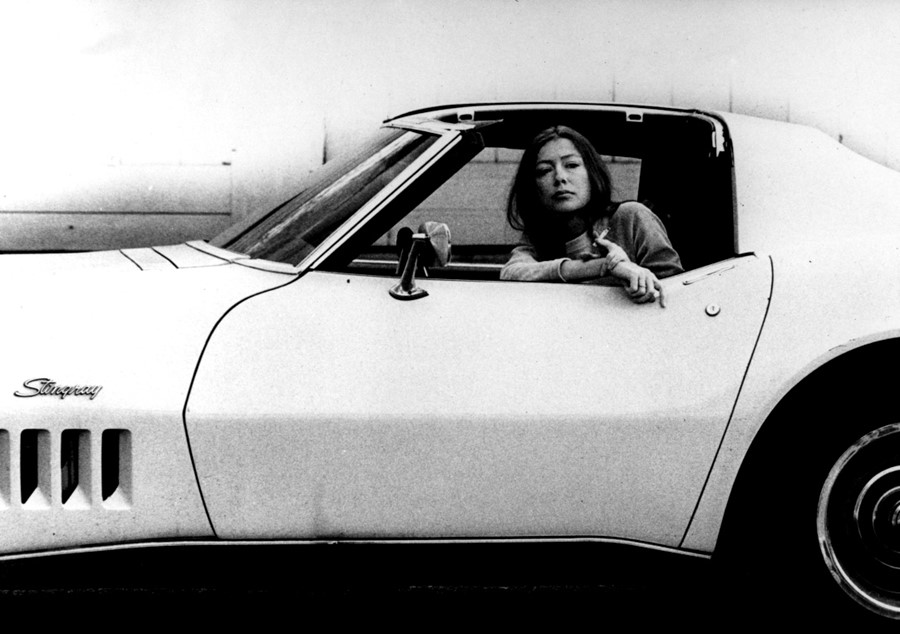

To mark Joan Didion's 79th birthday yesterday, AnOther celebrates the life and work of one of America's greatest writers

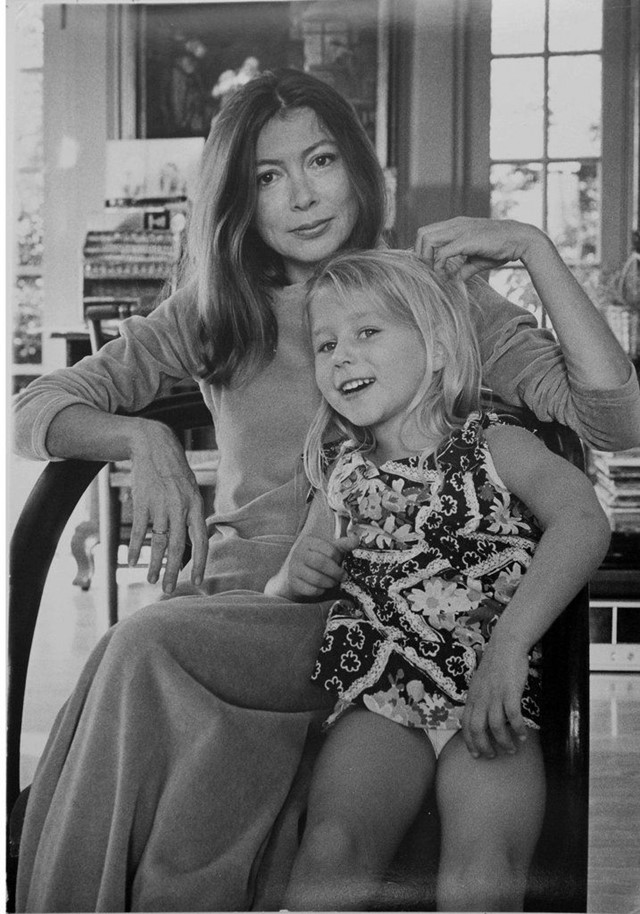

I was late to Joan Didion. Not late late, but still: three heartbreaks deep and filing tax returns. I’m slow at getting through books and unashamed to admit that there are still very big holes in my reading. During a walk over Hungerford Bridge a few years ago, a friend of mine told me the tragic story of Didion’s later life; how she lost her husband John Gregory Dunne, and daughter Quintana in quick succession and wrote about the ordeal in two books – The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights. Some books benefit from being read with a bit more experience, and I could have waited a while longer before reading these.

I didn’t give Didion a second thought until a few months later when I went to pick up a copy of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Didion’s first collection of non-fiction writing published in 1968. According to reviews, this was the definitive portrait of 1960s California, a world-renowned work of literature that anyone less consumed by heartbreak and filing tax returns might have read. Except that when I opened the first page it struck me as something I had read before, there being something familiar in the way it was written.

The second of the collection’s short stories, ‘John Wayne, a Love Song’ is perhaps my favourite, and begins with an account of how Didion spent one Summer returning to the cinema with her brother to watch John Wayne in War of the Wildcats. As she recalls, Wayne’s character decides to build his girl a house: “at the bend in the river where the cottonwoods grow.”

Later on she describes how in California, life is always spent on a sort of precipice. With only the Pacific ahead – and of course, given the book’s chronological proximity to the conflicts of the early Twentieth century – the threat of Japan. California is the edge of the mainland, where the American dream can go no further and must teeter or otherwise fall into the nothingness of the sea below. It’s a void that exists within the Californian psyche and a void that certainly found its way into Didion’s writing. Finishing Slouching Towards Bethlehem and moving on to the novels – Play it as it Lays and A Book of Common Prayer – then back again to the non-fiction – The White Album, Salvador and the latter two autobiographical works about her family – it became clear to me that this nothingness, this simplicity of expression, often suggestive by what it chooses to omit, is what underpins Didion’s writing.

In this way it is perhaps easier to compare Didion to artist Ed Ruscha than to other writers (although she has often cited Hemingway as a major inspiration). Nowhere does Didion resemble Ruscha more than in The Year of Magical Thinking, where motifs and phrases start, falter and repeat against the backdrop of a white page. Nowhere does Didion demonstrate more clarity than when she’s recounting the way in which her husband’s death destroyed her own sense of mental clarity. We are not reading an account of mourning. We are watching the mourning process unfold as it happens on the page in front of us: words beginning to resemble sentences beginning to resemble ideas, as the Year of Magical Thinking passes and reaches its conclusion. Except of course there is no conclusion, and she will forever mourn her late husband.

She is funny. Not LMFAO funny, but then she’s a writer, not a comedian. Part of my fascination with Didion came from the fact that I was reading her at a time when ‘being a writer’ seemed to be all about shouting the loudest, telling gags, tweeting incessantly and being professionally opinionated. Yet for all the stomping and shouting everyone was doing, none of the writers I’d encountered in today’s mainstream media looked like they would ever make such a profound or lasting impact as Didion, with her quietly measured prose. Her writing is not defined by gender, she is not consciously a ‘woman writer’; that said, she has certainly never compromised her femininity. She lives and she explores and she recounts her findings in a way that is good. Simple. Being the master of that skill is a feminist statement far more powerful to me than the reiterations of a ‘for us by us’ school of feminist writing.

It has also won her admirers across the board. Most famously Bret Easton Ellis, and by proxy, every person with half an interest in reading in the English speaking world. I eventually came to realise that the reason Didion’s work sounded so familiar on that first reading – and why I could happily sit and read her books every day for the rest of my life – is that it has trickled down to such an extent that today, we are all Joan Didion disciples, whether we know it or not. The wry glance that a generation of Ellis readers casts on the media, the entertainment industry and the political infrastructures of the West, begins with Didion. The media’s acceptance of the cultural importance of subcultures, begins with Didion. But to elucidate mourning, which in the West we are forced to endure without the proper rituals that other cultures have developed for the sake of recovery, is perhaps Didion’s greatest gift to date.

Text by Nathalie Olah