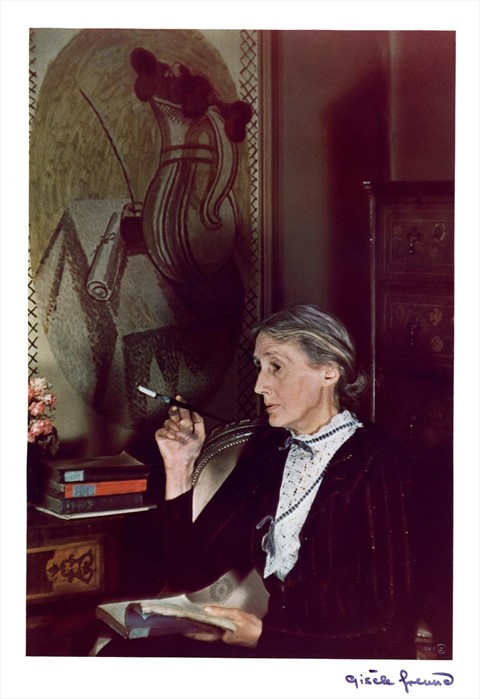

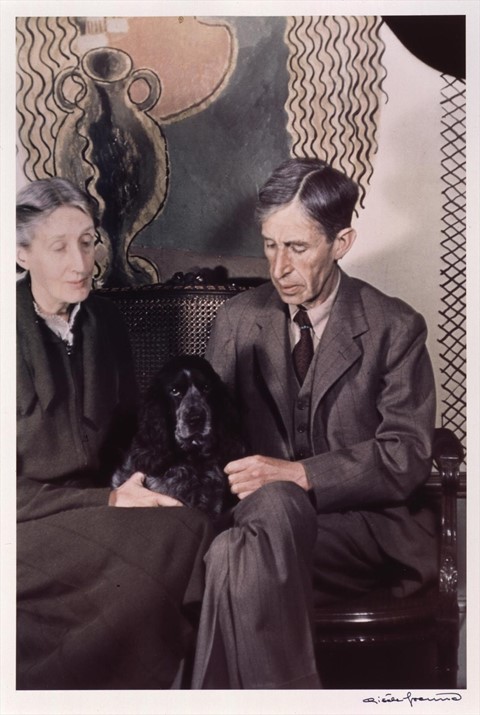

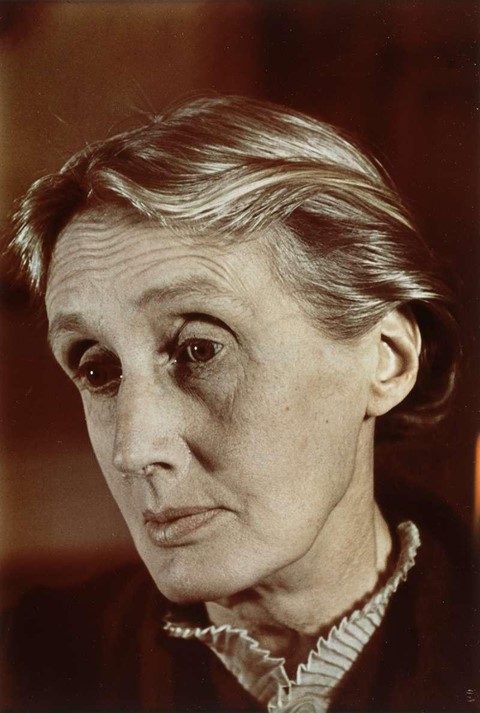

To mark the opening of an exhibition of portraits of Virginia Woolf at the National Portrait Gallery, AnOther looks at the life and work of one of Modernism’s most important literary figures

Virginia Woolf is famous for many things. She is famous, of course, for her novels – for writing about London, life, love and loss with a sense of colour and immediacy in the style of stream of consciousness (though watch out for literary critics, this is, in fact, called ‘free indirect discourse’). She is famous for her aristocratic parentage – her father was the eminent Victorian Leslie Stephen, whilst her mother, Julia Duckworth, was a pre-Raphaelite beauty, from whom Woolf inherited her silvery features and hooded eyes. She is famous for living in Bloomsbury, a literary landscape of shaded squares, cafés and omnibuses, street lamps melting into foggy London evenings when T. S. Eliot might pop in for tea. She is famous for her friends, known loosely as the Bloomsbury Group, which included the painters Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, art historian Roger Fry and the economist Maynard Keynes. She is famous for wartime summers in Sussex, where the Bloomsbury set gathered at Charleston in Lewes, a rose-covered farmhouse decorated entirely in the Post-Impressionist style.

She is most famous, sadly, for her lifelong struggle with mental illness, documented throughout her diaries and in her essay ‘On Being Ill’. On March 28, 1941, after writing a letter addressed to her husband – in which she wrote, “I owe all the happiness of my life to you” – Woolf put stones in her pockets and drowned herself in the River Ouse, near where she lived in Rodmell, Sussex.

The shadow that her suicide has cast on her work is hard to erase, though beneath the depictions of madness and melancholy in her characters (take Septimus Warren-Smith in Mrs Dalloway, for example) there is a ravenous appetite for life. Woolf wrote with colour, liveliness and humour about everything she loved – and often the most unusual things; a flowerbed, a snail on the wall, an entire novella dedicated to her friend’s spaniel. Here, AnOther examines Woolf’s more unusual subjects.

1. Virginia Woolf loved objects

“I shall have to write a novel entirely about carpets, old silver, cut glass and furniture,’ Woolf wrote to her sister, Vanessa Bell, in 1918. A diary entry of the same year records her covetous rapture at being given a green glass jar by her chemist. In her fiction, she devotes an entire short story to a protagonist who finds a lump of smoothed glass on the beach, and another to a woman who collects furniture. Throughout her novels, her characters are illuminated by the objects they own: pens and penknives, sewing scissors, pictures and books. Her own home, Monks House in Sussex, is testament to this thirst for bric-a-brac – it is decorated in bright colours, and dotted with ceramics, paintings and unusual objects.

Whilst she was writing in Bloomsbury, her sister, Vanessa Bell, was part of the Omega Workshops, which opened in 1913 under the direction of Roger Fry. The Omega was a design centre, where artists colorfully decorated textiles, ceramics and furniture, intent on injecting a sense of fun into interior design. Woolf was clearly influenced by the idea that domestic objects could be both useful and beautiful.

Most poignantly, Woolf used objects as a way of depicting a person’s absence. In Jacob’s Room, which was first published in 1922, we know Jacob is dead when his mother holds out a pair of his old shoes. Similarly, after Mrs Ramsay has died in To The Lighthouse, her green shawl sways emptily in the wardrobe of her crumbling house as a constant reminder that she is gone.

2. Virginia Woolf loved painting

In an essay about the artist Walter Sickert, published in 1934, Woolf declared, “Words are an impure medium – better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint.” Post-Impressionism was taking over London. In 1910, Roger Fry curated an exhibition at the Grafton Galleries, which included works from Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Matisse. The paintings were vibrant and controversial, experimenting with new perspectives and colour schemes. Woolf was enthralled, and attempted to translate a painterly use of colour into her prose. The experimental pieces ‘Blue’ and ‘Green’, written between 1917 and 1921, are visual impressions of colour concentrated into words. As her prose style developed, certain colours began to take on specific meanings: red came to signify psychological danger areas, such as Sapphic desire and madness, whilst green was consistently associated with the feminine and the maternal. In Mrs Dalloway, when Clarissa descends the stairs to greet her guests at her party, she is wearing a green silk dress. Similarly, Mrs Ramsay’s shawl in To The Lighthouse is green. Woolf had already seen, by the time these novels were written, Matisse’s ‘Portrait of Madame Matisse (the green stripe)’ and Sickert’s paintings, in which his female nudes were bathed in a green light.

“Words are an impure medium – better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint” — Virginia Woolf

But it wasn’t just with a painterly colour scheme that Woolf demonstrated her understanding of painting. She painted still-life compositions with words, reminiscent of the work of her Bloomsbury contemporaries Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Abandoned dinner tables, vases on windowsills and interior spaces are laid out before the reader’s eyes with the same formal arrangement as a work on canvas. These still life compositions are emphasized by other techniques – Woolf often employed the painterly technique of chiaroscuro, the use of strong contrasts between light and dark.

3. Virginia Woolf loved flowers

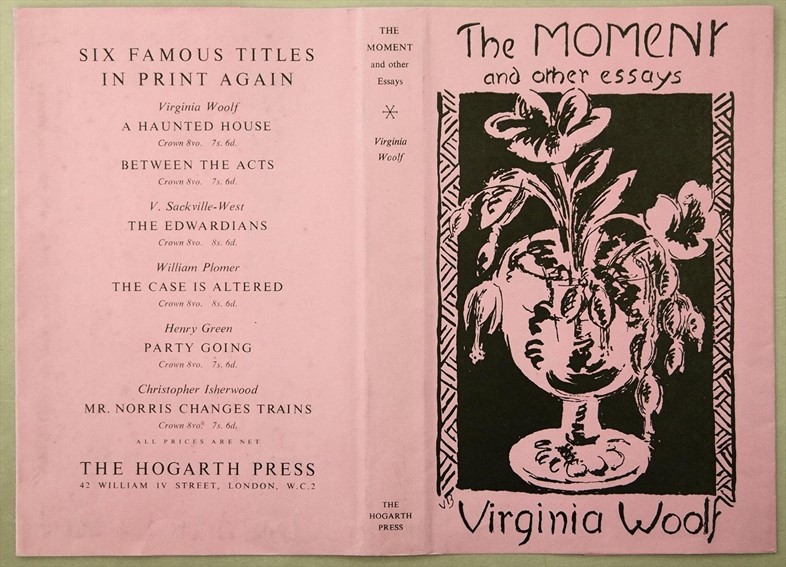

Images of roses, orchids, lilies, poppies, tulips, crocuses and violets are scattered throughout Woolf’s fiction. An early short story, Kew Gardens, published by the Hogarth Press in 1919, begins with a colour-saturated description of a flowerbed. Woolf used floral colour and symbolism to create visual shorthand for the meaning of flowers. They are Sapphic – Clarissa Dalloway remembers when her would-be lover “picked a flower, kissed her on the lips”. But they are also reminders of human mortality. In the closing scene of The Years, Woolf’s penultimate novel, published in 1937, the abandoned dinner table is strewn with dirty plates and crushed petals, reminding us that each generation of the Pargiter family will perish as the one before it.

But flowers also featured heavily on the covers of Woolf’s novels. In 1917, Leonard and Virginia bought a hand printing press with the intention of publishing limited editions of Virginia’s novels. Woolf enlisted her sister, Vanessa Bell, to design the book jackets. Bell’s cover designs recall Bloomsbury still-life paintings, with exaggerated long-stemmed flowers spilling from round vases, printed on coloured paper. It is here, in the composition of the still life both on the book cover and in the prose within, that the close relationship between the sisters’ art is most clearly realised.

4. Virginia Woolf loved women

Much documented is Woolf’s relationship with Vita Sackville-West, which began after the women met in 1922, shortly after the death of Katherine Mansfield, with whom Woolf had enjoyed a close correspondence. Though their friendship got off to a shaky start (Woolf initially thought Sackville-West was posh and stupid, and called her ‘donkey West’ throughout their relationship) they were soon writing to each other constantly, though they stayed with each other infrequently throughout their romance. Woolf’s sexuality occasionally revealed itself in her work. There is Orlando, a novel based loosely on Vita’s ancestral past, in which the central figure switches from man to women as he/ she moved through the ages. Later, Vita’s son would remark that it was “the longest and most charming love letter in literature”. In Mrs Dalloway, Clarissa falls in love with her childhood friend, Sally Seton, whilst in To The Lighthouse, Mrs Ramsay’s death is mourned for a long time afterwards by the spinster Lily Briscoe. Close, complex female relationships exist throughout Woolf’s work, allowing glimpses of a side to Woolf that she acknowledged, but could never give full expression to.

Woolf was devoted to rights for women, becoming politicised from the late 1920s and preoccupied with the subjection of her sex. She published A Room of One’s Own in 1929 and the more vehement Three Guineas in 1938. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf muses on women in society, life and literature in an ironical, conversational way, declaring that (and this was 1929), women needed only £500 a year and room of their own in order to write. The essay was an important contribution to the feminist debate, and is still on reading lists for women’s studies today.

5. Virginia Woolf loved London

Woolf spent her childhood years at 22 Hyde Park Gate. Here, she lived with her siblings – George, Stella, and Gerald (from her mother’s first marriage), and Vanessa, Thoby and Adrian. It was a busy household, full of literature, conversation, and guests including Henry James. The children wrote The Hyde Park Gate News, a miniature newspaper that recorded the daily activities of the house.

Woolf suffered the death of her mother at the age of 13, which resulted in her first bout of mental illness. After her father’s death nine years later, and another breakdown, the family moved to Bloomsbury. Aside from years spent in Richmond, and her eventual move to Sussex, Bloomsbury would form the core of Woolf’s London literary life. She lived on Gordon, Tavistock and Mecklenburgh squares, and witnessed the devastation of the area during the bombing of London during the Second World War, at one stage having to search for her diaries and notebooks among the rubble.

But despite the air raids, Woolf wrote her best fiction in London, devoting whole stories to summer strolls in its parks and gardens, or evening adventures into the streets in search of a pencil. Mrs Dalloway is a lively walker’s guide to London, as the reader follows Clarissa “in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar… in the triumph and the jingle” of the bustling city. Woolf’s characters buy flowers in bright florists, take omnibuses along the Strand, doze off in Regent’s Park, eat pork cutlets in cafés and attend literary and political meetings in all manner of drawing rooms.

Woolf loved the bustle and the roar of the city. She wrote writing guides to London and pieces on shopping in the city for magazines like Good Housekeeping. Though Leonard tried to pull Virginia away from the city, in order for her to rest and recover, she always found her way back, to return to her favourite pastime of ‘street haunting’.

Virginia Woolf – Art, Life and Vision runs at the National Portrait Gallery until October 26.