We present the first look at Luella Bartley and Zoe Taylor's exquisite monochrome fairytale, inspired by their adventures at Port Eliot Festival

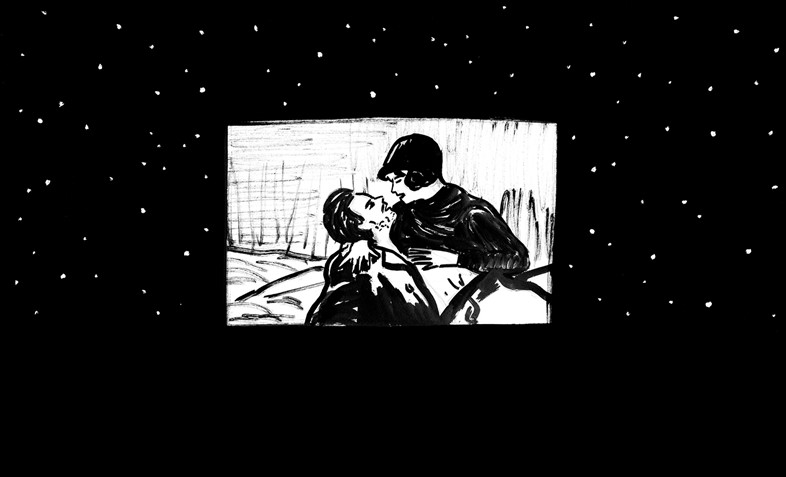

Two years ago, in the Elysian fields of Port Eliot, designer Luella Bartley and illustrator Zoë Taylor collaborated on a graphic story project inspired both by their surroundings and the words and wisdom of the festival’s 2012 participants. The result was The Girl Who Fell to Earth, a fairy tale "of feminism and freedom", that tells of a princess attempting to break free from the tyranny of rationalism to enjoy the more whimsical, romantic, human sides of life. Taylor depicts the princess’s adventures in monochrome vignettes, punctuated with bon mots from the likes of Geoff Dyer, John Cooper Clarke and Stephen Frears, while Bartley’s story is a decidedly modern take on the damsel in distress narrative – leading its heroine not into an ivory tower, but to a forest glade, lit with a disco ball, populated by handsome, long-haired musicians.

Bartley and Taylor's story has now been turned into a book and the pair are back in Cornwall to present the work to the audience who inspired it. So to celebrate its launch, here we present the first chapter from The Girl Who Fell to Earth.

There was once a beautiful celestial Princess who lived in a high, imposing castle constructed of dense rock and ice on the ninth ring of Saturn, in darkest Space. She lived with her father, the King, who was kind but self-important and of a very nervous disposition. He was also a terrible listener. But he provided extravagantly for his people, and in return, his people remained dutifully submissive, though they lived a monotonous and unimaginative life.Indistinguishable in character from their environment, the people, although academically gifted, lacked any surface character and even their Saturnian outer atmosphere was well known to neighbouring planets to be bland and lacking in contrast.

The Ringtarians, so-called as they inhabited the ninth ring of Saturn, were a race of meticulous mathematicians and architects, and they built majestic and intricate structures out of the ice, rock and remnants of old moons that surrounded them. But the protection these structures provided seemed more like confinement to the fidgety Princess.

While her father’s days were spent overseeing his vast, monotonous ice kingdom, the Princess’s hours were filled with domestic chores and uninspired learning. In her mornings she helped the Royal Nutritionist collect and prepare the chemical formula that constituted the grey, rather tinny tasting gruel that they consumed.

In her afternoons she would fill time by hiding from her irritable Physics & Religious Studies tutor (physics was the religion around here), sulking in various corners of her massive castle, carving her transcendent dreams in ice – elaborate whims of flight and intimate studies of her imagined life on far-off stars. She also enjoyed writing poetry about the death of morons.

Her life, she felt, was tenuous. The Princess desired something more expressive, more heart-wrenchingly heroic.

Hers was a melancholy longing and she felt desperately lonely in her restlessness. She lived as a romantic in a kingdom of masculine logic. A pallid kingdom, she was sure, would never be able to satisfy her heart’s gnawing disgruntlement. Like a butterfly encased in a dark cocoon that tightened around her every time she tried to spread her pubescent wings, the Princess grew ever more wretched. From the excessive levels of gravity that conspired to drag her down, to her father’s relentless common sense, all seemed oppressive.

Lately, her father, whom she had once worshipped, seemed simply a tiresome extension of the dark smog-filled clouds that hung above her, the relentless racing winds and pompous gas that encircled her. Thinking about him made her stamp her feet at the rigidity of her surroundings, and kick against the cold ice walls in anger.

Ringtarians had long comforted themselves by celebrating the pragmatism of reason but the subversive Princess scoffed at and pitied their small-minded rationalism. In her heart, she believed that there must be more to life than varying degrees of geometry. For all the cold, silvery beauty of the sixty-two moons she stared at day after day, there had to be some kind of balance in the universe. Something brighter, more vibrant, warmer, more FUN!

The Girl Who Fell to Earth by Luella Bartley and Zoë Taylor launches today at Port Eliot Festival. See more of Zoë Taylor's work for AnOther's In The Cut column here.