We investigate the sinister dioramas of Francis Glessner Lee, a society matron who transformed forensic science

Much has been made of the ghoulish predilections discernable in the Nutshells of Unexpected Death. These minutely detailed scale models depicting grisly death scenes are, to some, grotesque subversions of the innocent dollhouse. In one scene, a doll is strung from an attic laundry line, her shoe half off; in another, a female form is slumped half out of a bath, her skirt rucked up, her legs skewed unnaturally, a stream of water gushing into her mouth; in a three room dwelling, a mother, father and baby daughter lie drenched in pools of blood, a rifle discarded on the floor. Detailed down to the date on a calendar, or the fraying on a dishcloth, at first glance the Nutshells seem a product of our death-obsessed age, horrifying vignettes representing the eternal human fixation with murder.

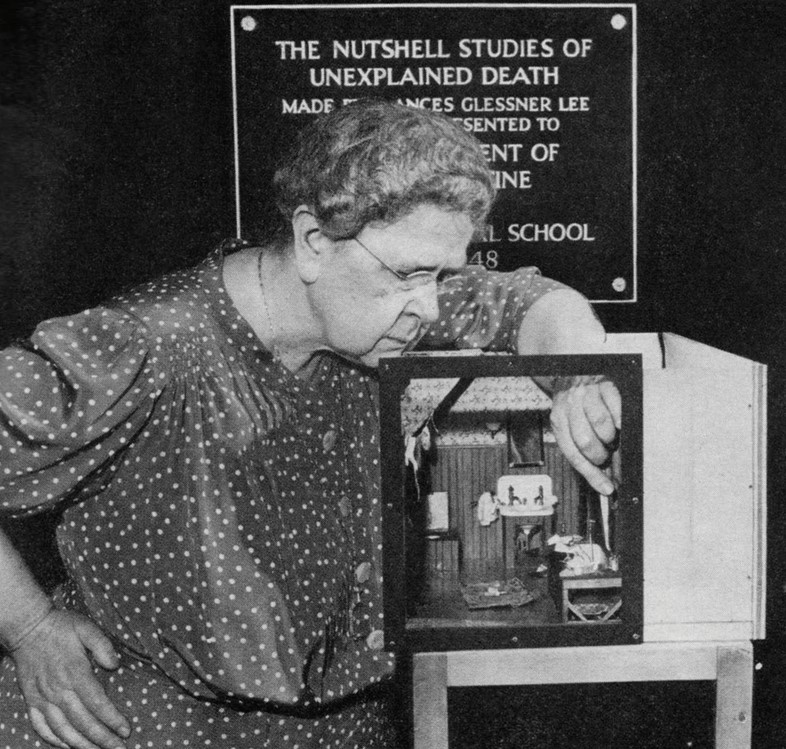

The reality is unexpected, for while the Nutshells were indeed the work of a crime obsessive, the obsession served a strictly scientific purpose. Instead, they were the life project of a society matron from 1940s Chicago – allegedly the inspiration for television’s favourite master sleuth Jessica Fletcher – who, with their creation, fundamentally changed the face of forensic science and crime investigation.

"While the Nutshells were indeed the work of a crime obsessive, the obsession served a strictly scientific purpose"

Francis Glessner Lee is the most unlikely scientific pioneer. Born in Chicago in 1878, home-schooled and denied the college education she so desperately desired, her life followed the pattern established for those of her class: trained in the feminine arts of needlework and interior design, married at twenty to eligible young lawyer Blewett Lee, mother of three. An encounter in her twenties with the young legal doctor George Magrath awoke a passion for forensic science that would become the central tenet of her life, one that she was only able to pursue at the age of 52, when she inherited a fortune on the death of her brother.

She used the money to found the world’s first department of legal medicine at Harvard, but by far the most intriguing of her legacies are the Nutshell Studies of Unexpected Death. The Nutshells – named for a detective saying that described the purpose of an investigation to be “to convict the guilty, clear the innocent and find the truth in a nutshell” – are accurate dioramas of crimes scenes frozen at the moment when a police officer might walk in. Details were taken from real crimes, yet altered to avoid identification and enlarged to create the most complex scenario possible.

Precision was everything. The scale was 1ft to 1”. Every key turned in its lock, every blind could be pulled down, every pencil wrote, every closet was hung with clothes. She attended innumerable autopsies to understand the precise discoloration for victims at various stages of decomposition, she hand knitted tiny socks using straight pins to ensure accurate size of stitches, and wore a blue suit for a year to create the worn effect for a victim’s trousers. In order to create the burnt cabin of one nutshell, her carpenter built a perfect wooden hut, and promptly burnt it down using a blowtorch. These were not effigies of a crime scene; they were exact replicas.

To many, this level of detail seems absurd, mad even. But the Nutshells are precise for a very good reason – because they absolutely had to be. They were created not as whimsical whodunits, but as training tools for law enforcement officers learning how to address a crime scene, and any disparity with fact would have rendered them worthless. It is by virtue of Glessner Lee’s mania for veracity that the Nutshells remain not only extraordinary, but in use to this day by the Harvard Associates in Police Science seminars. And it is for fear of undermining these training programmes that is not possible to reveal publically the solutions to any of the depicted crimes.

In recognition of her work, Glessner Lee became the first female member of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, was made Honorary Captain of the New York State Police and is remembered – in legal medical circles at least – as the “patron saint of forensic medicine”. However in modern society, a first glimpse of the nutshells, in all their domestic precision and clutter, the tiny ketchup bottles and the wilting houseplants, speaks not to our scientific selves, but to our obsession with the macabre, with murder, with crumpled corpses and unsolved crimes. When viewed as spectacles, the precise blood spatter, the lipstick on the pillow, the blueish tint on a baby’s cheek become grotesque, a near abomination – yet remove them from the ghoulish eyes of the public, and place them back under the flashlight of a forensic investigator and they lose their horrifying nature, becoming science once more. This is the dual nature both of the nutshells and of obsession itself – to understand the Nutshells and the aims of their creator; we must push aside our own fixations and fears.

One of the Nutshells will be on view as part of Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime at the Wellcome Collection from February 26 - June 21.