In Yoko Ono’s latest installation artwork, Das Gift, at Berlin’s Haunch of Venison, the artist takes the viewer down a passage to freedom, inviting them to actively engage in the work. The themes explored are of violence and memory, the personal and

In Yoko Ono’s latest installation artwork, Das Gift, at Berlin’s Haunch of Venison, the artist takes the viewer down a passage to freedom, inviting them to actively engage in the work. The themes explored are of violence and memory, the personal and the global, and, naturally, of peace.

The title for the exhibition was found in an old bookshop where Ono came across the German word “gift,” which translates as poison. She chose it as, for her, the show is about the poison of the world, which she believes we should learn from, and also because a present can be poison; it tastes good but can bad for your health.

In another work, Helmets, old German soldiers’ headwear from the great wars creates a forest and is filled with puzzle-sized pieces of the sky, which can be taken home.

A canvas in the main room of the exhibition space, entitled Heal, invites us to take part in the repairing of rips and cuts, signifying the mending of yourself and the world as you do so. Hole is perhaps the most significant piece in the show. A work of engraved glass in a steel frame, shot through with a bullet, the viewer is asked to change their position twice to observe it: once from the front, making them the aggressor, and once from the back, rendering them victim.

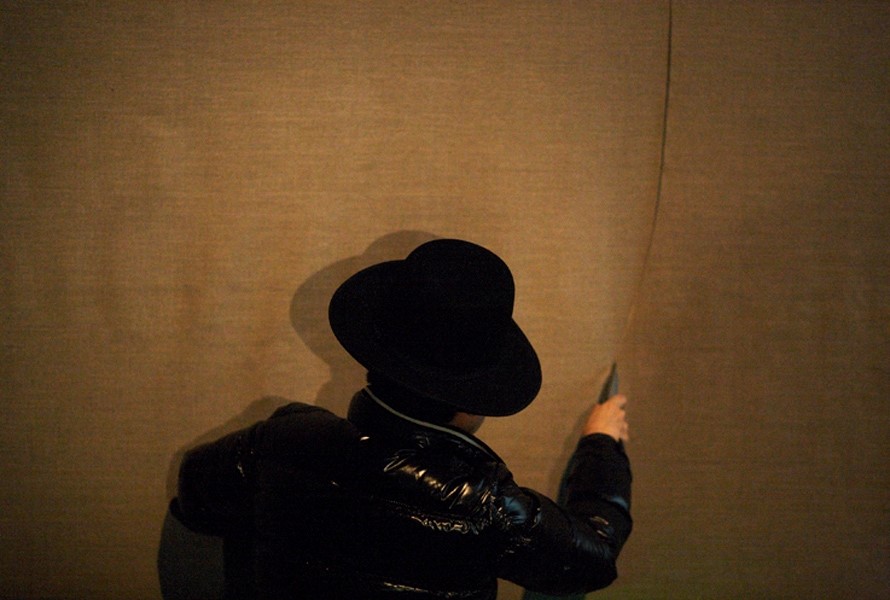

Ono is pointing to violence all across the world. Her piece Coats is made up of seven hanging coats with bullet holes belonging to people who were shot while wearing them. She invites us to walk through the coats and mix our own shadow with theirs.

She deals with her own experience of violence as well as that of Berlin. In the room The Passage for Light, nine canvases of street maps of the German capital from different periods hang on the wall. The artist asks Berliners to pin a photograph, a letter or something they have written onto the works to share a personal memory of violence from a particular time.

In Ono’s opinion Berlin’s history of violence is no different from the atrocities currently happening around the world. “There is so much pain, violence and abuse in the world now, and if you don’t release it you’re holding it in and it will fester and make you unhealthy,” she says. Ono is daring the viewer to expose their pain and memory, believing it becomes something more positive, especially when other people see it. “We share the same memory because we’re the human race, and with the memory of violence we can get together and create a new world.”

Ono sees Berlin as a very peaceful city, filled with creative people. “It’s a pleasure to do an installation here and know that we’re speaking the same language,” the artist says, adding that she sees it as “a group meditation of creativity.” The artist explains her own experience of violence as not being worse than anybody else’s, or than what is happening in Iraq or any of the other countries. But there was a time in her life, she says, when she could have drowned or survived, and she chose to survive. “When you stand in front of each work you will see something that you know. I’m asking you to participate so you don’t just look at it but you become part of the piece, because you recognise.”

The final installation of Das Gift is Smile, for which Ono asks the viewer to sit in front of a camera and give their smile to the world from Berlin as a petition for peace. “In the end we all smile together, and that’s how we’re going to make it.”

Das Gift is on show at the Haunch of Venison, Berlin, September 10 to November 13