Jarvis Cocker and James Brett explain their additions to the Museum Of Everything

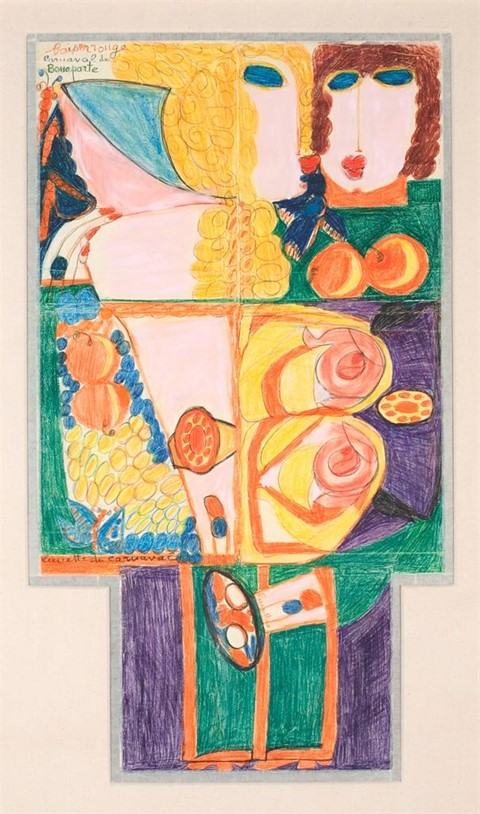

The Museum Of Everything is one of the most unmissable art exhibitions in recent memory: a massive collection of artworks created by those mysterious visionaries who live on the outskirts of sanity. Hand-picked by the likes of Nick Cave, Grayson Perry and Jarvis Cocker, this strange bestiary of the troubled creative mind was conceived by curator James Brett. On a frosty November morning, I shared a pot of tea with James and Jarvis (who was preparing to host a rare screening of his three-part series on outsider art, Journeys Into the Outside), to talk voyeurism, frailty and cracked genius...

Does outsider art have so much power because it’s so unselfconscious? Do you think it taps into something voyeuristic in the viewer?

Jarvis Cocker: That was part of what appealed to me about it when I was at art college – that it was about people creating things because they were compelled to do it. It’s fascinating that people are tapping into something within themselves that isn’t taught, something that is instinctive. But the voyeuristic thing? I suppose that’s a question you have to ask yourself when you are looking at it – am I only interested in it because this person had one leg and killed chickens?

Do you think we romanticise some of the work simply because it’s found? Would Henry Darger, for instance, have found critical acclaim if he had actually sought it?

JC: I don’t think he would’ve been able to produce work like that if he’d been doing it with the idea that people were going to look at it. It was something that obviously performed some function for him that wasn’t for anybody else.

James Brett: Essentially you are showing somebody’s diary, but art history is full of people showing work by artists who, in fact, wanted to destroy their work.

There were a lot of people wandering around the Darger exhibit saying, ‘This is obviously the work of a latent paedophile.’ Do you think that is a lazy reading of the work?

JC: It’s impossible to say really. Creative impulses don’t always come from nice places.

JB: I get pissed off when people say, ‘Well, he’s a paedophile...’ If you look at his work you can see that the point of view is always from the children, and that it’s not very sexual. It’s much more to do with what had happened to him, and the book is actually him telling his childhood over and over again. But in this version he can be the kids, and he can escape and live happily in the forest.

These artists are often very psychologically frail people...

JB: I think we are all psychologically frail, and maybe that’s why it connects. I like the edges of things, and somehow this sort of work feels much less mannered than the art world for me. It is definitely the aesthetic that leads me in, not the stories. Having said that, the stories are very engaging.

JC: I think a lot of this art is about people finding something that they can be in control of. It’s often by people who, in the rest of their life, are not in control. Here, they are the ruler of their own kingdom. That’s a nice thing about the exhibition. It’s not a downer. I think the general atmosphere of the place is quite joyful. It’s not like, ‘I’m stuck in a mental institution, help!’ The thing that I most value about this kind of art, and also why people react to it, is that it’s a bit endangered. The kind of definition of outsider art is that it’s by people who have grown-up outside of the cultural norms, who don’t get exposed to the same things as everyone else. It’s pretty hard to grow-up like that now, in a world where we are surrounded by the media. People aren’t in isolation anymore, and a lot of this work was created in isolation.

Do you have any plans for more exhibitions here?

JB: It would be good to have an exhibition of dreams.

John-Paul Pryor is Arts & Culture Editor at Dazed Digital and writes for Dazed & Confused, TANK, Another and The Quietus His debut novel Spectacles will be published in 2010 by Seabrook Press