We celebrate the work of Eve Arnold, the photographer who broke the mould for women behind the lens

“Being a woman is just a marvellous plus in photographing. Men like to be photographed by women, it becomes flirtatious and fun, and women feel less as if they’re expected to be in a relationship.” Whatever she may have said, Eve Arnold’s success in the male dominated world of photography was due less to her gender and more to her extraordinary talent and determination – compounded by her capacity to forge intimate relationships with her subjects. The photographs – tender portrayals of Hollywood legends, expositions of political figures such as Malcolm X and Joseph McCarthy that prompted censure and death threats, revelatory stories shot in China, Egypt, Afghanistan, Apartheid South Africa and the boarding schools of England, a vast repertoire of advertising work – speak to a life spent observing the shifting plates of 20th century history.

A new book, written by her friend Janine di Giovanni as part of the Magnum Legacy series, is a joyous journey through Arnold’s exceptional life, shown through the people she photographed over more than 50 years. The first woman to join the New York branch of the Magnum agency, she was a pioneer and an innovator whose extraordinary work spans the glory days of photo-journalism and remains visceral and emotive to this day. To mark the release of this new book, we delve into the stories some of her most famous photographs, investigating the relationships that made them and the thoughts of the photographer herself.

Marlene Dietrich, Columbia Studios, 1952

Having joined the agency’s inaugural New York office in 1952, one of only two female photographers on their books, Eve Arnold’s first job for Magnum was shooting Marlene Dietrich during a recording session at Columbia Studios. The filmstar was staging a comeback, recording an album of the songs she had performed for the troops during the war. Dietrich worked, dressed in a cocktail dress and diamonds, “like a ditch digger…from midnight when she arrived until six in the morning” and Arnold photographed her throughout. The resulting images were a new take on the film star portrait – fashioning an intimate view of a performer at work, rather than one cavorting knowingly for the camera.

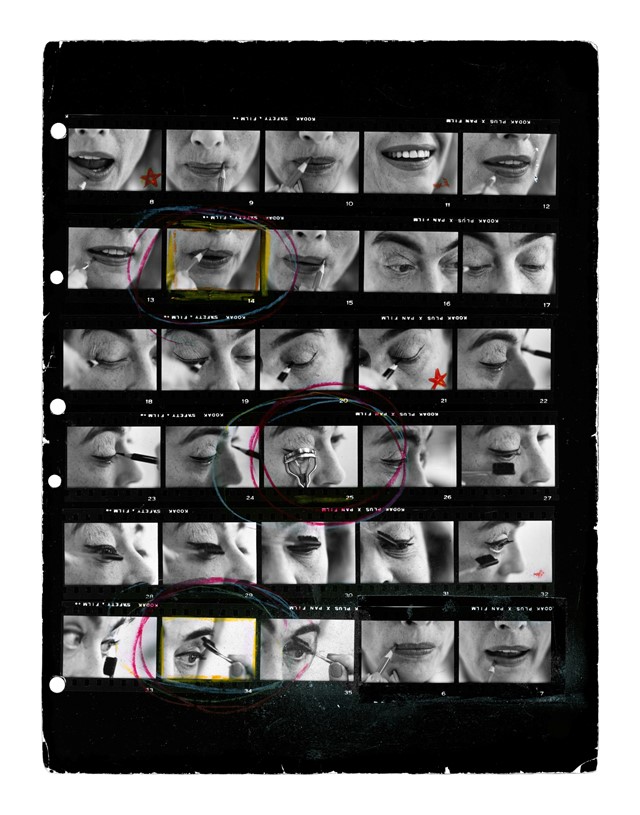

Joan Crawford preparing for a role, 1959

Eve’s first encounter with Joan Crawford was a fraught one. The actress arrived drunk, stripped off all her clothes and demanded that she be shot naked. Concerned that Crawford would be ultimately fuirious with the outcome of the images, Arnold did the shoot but gave Crawford back the negatives without showing them to anyone else. This act of loyalty was rewarded three years later in a deeply intimate story for Life Magazine, depicting Joan’s intensive physical preparation for a role. Detailing everything from leg waxes and girdle fittings to facials and precise make-up in an exhausting shoot that extended over many days, Arnold created a “modern, provocative” story, “undermining the myth that beauty is intrinsic, she showed what hard work is involved in presenting yourself to the world as a star.”

Pretty Polly ad, London, 1960

Eve was unromantic about the necessities of a life as a working photographer. “If one regarded each advertisement as a problem to solve and as a healthy fee to bank,” she wrote, “it just broadened the area of photography in which to operate.” And so began a lucrative career working in the commercial sector, on everything from Pretty Polly and Insurance ads to Sharwoods Curry Powder. She worked on a number of cigarette campaigns, unpleasant shoots involving smoke being blown in her face for hours on end, which eventually caused her to try and stop smoking.

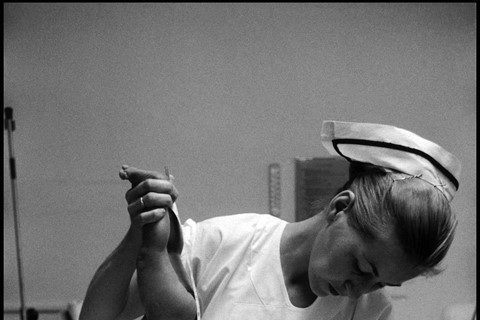

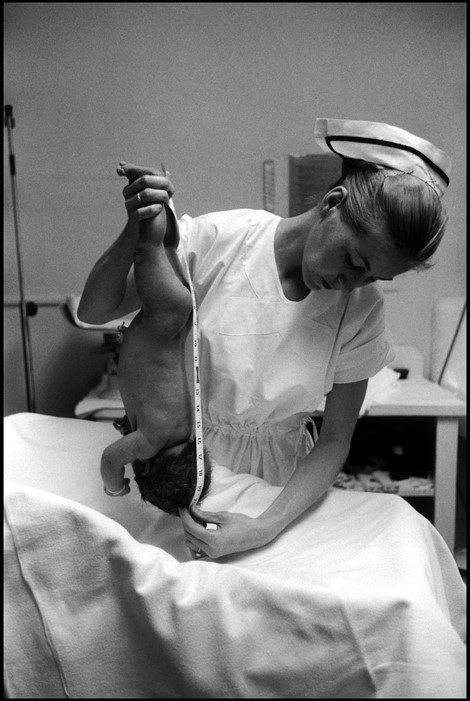

A Baby’s Momentous First Five Minutes, 1959

Late on in the 1950s, Eve suffered a miscarriage that resulted ultimately in a hysterectomy. A tremendous blow, the operation caused a profound depression, one that she sought to battle in a close up study of the mechanics of birth at Long Island’s Mather Hospital. She spent a number of months observing and photographing mothers in childbirth, resulting in an essay for Life Magazine detailing the extraordinarily ordinary drama of a baby’s entry into the world. “The cord is cut,” she wrote, “the child is slapped…tagged…footprinted…weighed…washed…anointed…measured…swaddled.” As brilliantly represented by this shot of a nurse measuring a newborn, her pictures melded the perfunctory everyday routine of the medical staff with the individual drama of families whose lives were changed forever, while her picture of a newborn holding his mother’s finger became a classic – as Arnold wrote herself, “this picture has been used to advertise everything from insurance to corn flakes,” its success funding her subsequent artistic projects around the world.

Marilyn Monroe on the set of The Misfits, 1960

Eve and Marilyn met in 1954, with the actress collaring the photographer at a party with the words, “If you could do that well with Marlene, imagine what you could can do with me?” Their first shoot was that year, a freewheeling day on a Long Island beach, the star playing ball games with Eve’s seven-year-old son Frank, beginning a relationship that would last until the actress’s death in 1962. But it was during the filming of The Misfits, a gruelling shoot in the unbearable heat of the Nevada desert, that Arnold captured the most intimate and affecting pictures. “She was a sort of valiant, funny, witty woman when I met her at first,” Arnold said of Monroe. By the time of the Misfits, she was “still all of that, but there was a string of sadness underlying it.” The set was not a happy place, director John Huston was drinking heavily, Clark Gable was unwell – he would die of a heart attack ten days after the film wrapped – and Monroe’s marriage to the film’s writer Arthur Miller was collapsing. Against the vivid desert backdrop, all vast skies and transcendent light, Arnold captured moments of vulnerability, creating a very human portrait of an idealised world creaking at the seams.

Eve Arnold, published by Prestel in association with the Magnum Foundation, is out on April 1.