A new exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton explores the artistic steps that created the idea of Modernism

The first half of the 20th century was a period of intense social, economical and political change – in art perhaps more than anywhere else, where the constant search for progress resulted in a magnitude of artistic experimentation. A permanent mirror of its time, art reflected the development of what we now consider the height of modernity. Marking the opening of Fondation Louis Vuitton’s exhibition on modernity Keys to a Passion, we present you 10 essential moments of modernity.

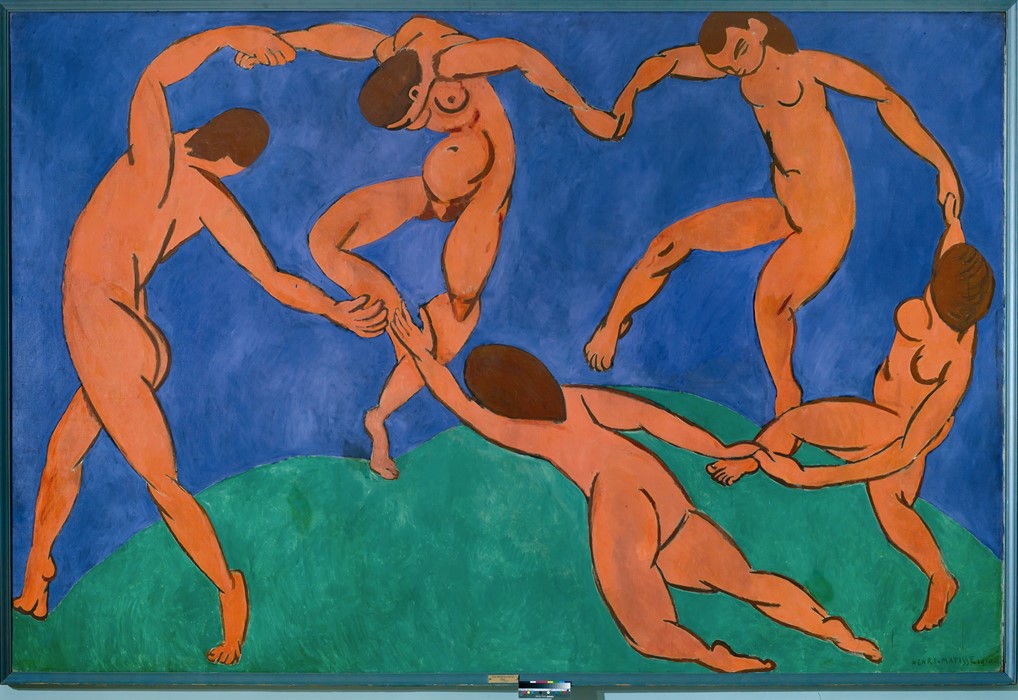

Henri Matisse, La Danse, 1910

Classified once as the father of Fauvism, Matisse moved across mediums throughout his career, constantly challenging the conventions of representation. His sense of light and colour has made one of the most important painters of the 20th century. La Danse is an iconic study of movement – the wild and ecstatic is caught here in a Dionysian ritual of music and pleasure. The naked figures are simplified to almost child-like shape so as to emphasise immediacy. Stylistically, the painting references 'primitive art', and reflects the young artist’s interest in the primal and barbaric – he prioritises expression over representation, a bold and avant-garde move in 1910. Perhaps his most important commission ever, Matisse painted the massive painting for the millionaire Sergei Shchukin’s Moscow palace – a preliminary, much less vivid sketch is at display at MoMA New York.

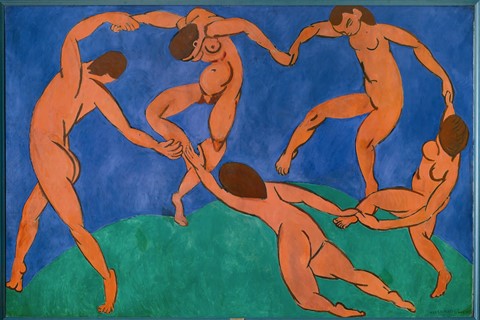

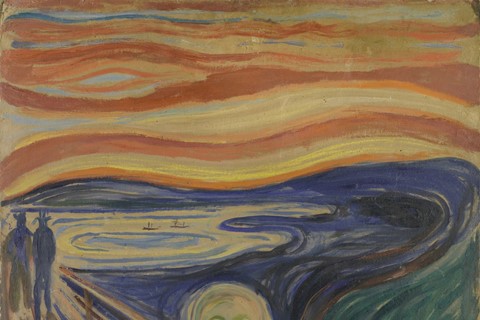

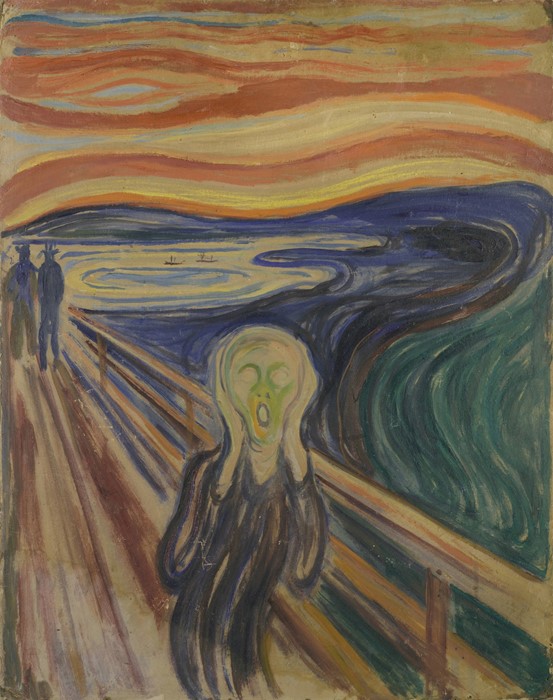

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910

It has been dubbed the 'Mona Lisa of modern times', famously re-appropriated in popular culture (from Warhol silk-screens to The Simpsons) and victim of some of the most famous art thefts in history. Painted in the time of Freud and the emergence of psychoanalysis, The Scream is a haunting representation of psychological crisis – supposedly inspired by Munch's own schizophrenic sister. Here, Munch rejects naturalism to approach the horror of the mind more honestly. The madness, however, is far from only personal – it evokes a sense of complete despair, of all the chaotic madness of the world.

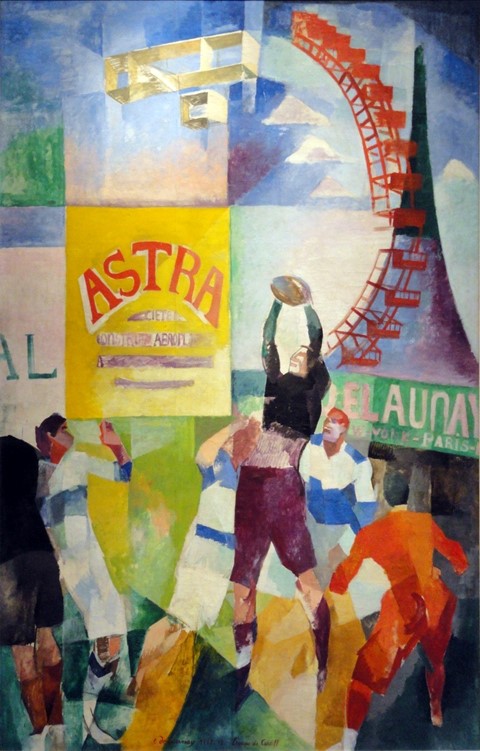

Robert Delaunay, The Cardiff Team, 1912–13

The Frenchman Delaunay came from a background in theatre design, and was never formally trained as a painter. A true modern man, he was always celebratory of the City, with its advancements in technology, rapid revolutions in fashion and expansion of its cultural scene. The Cardiff Team is his love-letter to the Parisian urban space, depicted in the dynamic fashion that he perceived it. Ferris-wheels, billboards and the Eiffel tower merge with the movement of humans in a chaotic mixture of vibrant colours, painted in the style of Orphism, an offspring of Cubism that he co-founded with his painter wife Sonia Delaunay.

Claude Monet, Blue Water Lilies, 1916-9

Despite the rapid industrial advancement and an intense expansion of material life, artists continued to return to the meditation of nature throughout the 20th century. Particularly water evokes the contemplative mode of life, and for French impressionist master Claude Monet, his beloved water lilies in his garden pond in Giverny outside Paris (today a major tourist attraction) became a recurring source of reflection on his medium. With his water lily paintings, he captures an infinite level of diversity in the shallow water plane and its reflection of light, proving that capturing a scene or a mood entails much more than depicting it’s visual accuracy. This became a founding principle for the Impressionists, who changed the shape of modern painting.

Fernand Léger, Three Women, 1921

Three Women marks a key moment in the more and more personalised form of cubism in Léger and generally, in painting at the time. Increasingly abstract, he nonetheless returns and duplicates the most iconic figure of all: the female nude. The cleansed colour palette and tubular-formed bodies show his interest and attraction to futurist industrialism and the Bauhaus, which developed around in his time – the placement of the figures in a futuristic interior confirm the modernity of these women. As such, Three Women is a useful portrait of Léger’s context - an amalgamation of the many artistic and political currents in Europe that influenced the young painter in the 20’s.

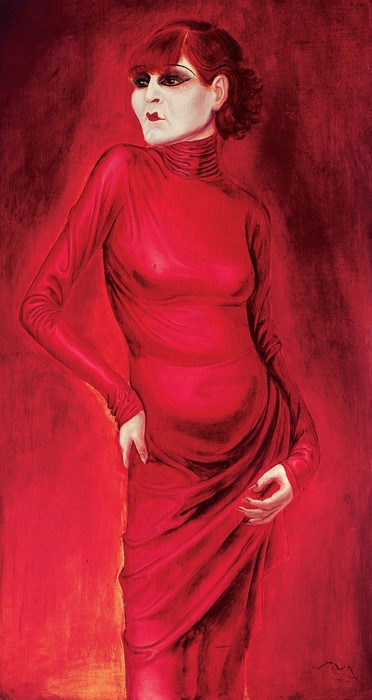

Otto Dix, The Dancer Anita Berber, 1925

Berber was a notorious figure in the glitzy nightlife of 20’s Berlin, a time famous for its hedonistic joie-de-vivre, artistic experimentation and personal sexual freedom. Trained as a dancer, she frequented the avant-garde scene and performed cabaret – known for her shameless frivolity (she was once imprisoned in Zagreb for 6 months after publicly insulting the king of Yugoslavia) and easily recognisable fire-red hair. Her rumoured bisexuality, nihilistic lifestyle and celebrity status made her an icon of pre-war Europe – and a precursor of the celebrity culture that has since followed. Dix, him self an avant-garde and a celebrated developer of New Objectivity saw the importance of capturing popular culture in painting – and does so here in his trademark fashion: brutally honest, yet always celebratory.

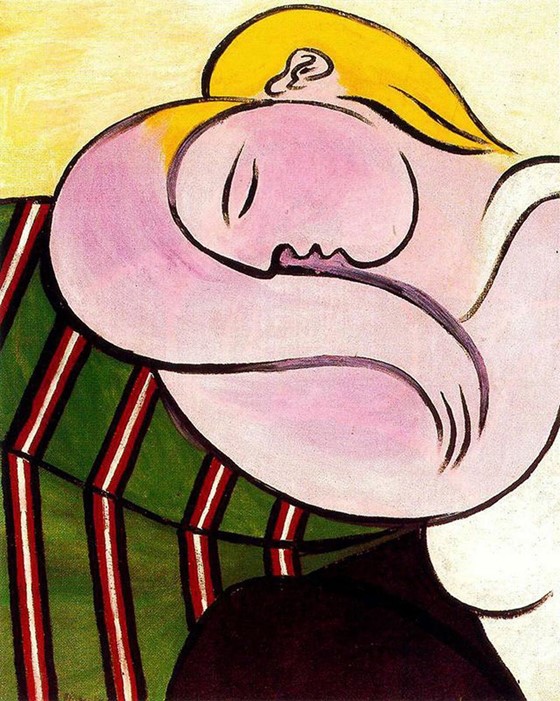

Pablo Picasso, Woman with Yellow Hair, 1931

The master of modern painting reconfigured his practice too many times to count, constantly changed his technique, medium and theme – in other words, a true modern artist. Cubism however seems to have been longitudinal passion for Spanish-born Pablo Ruiz Picasso – who painted this elegant portrait in the style of Synthetic Cubism in 1931, as a reaffirmation of cubism’s importance within an increasingly Dada-oriented avant-garde. It depicts the young model Marie-Thérèse Walter, who initiated a secret love affair with the painter at the age of 17, eventually giving birth to his son. Subject of some of Picasso’s finest portraits, she was but one of his many mistresses – she ended her life tragically shortly after his death in 1973.

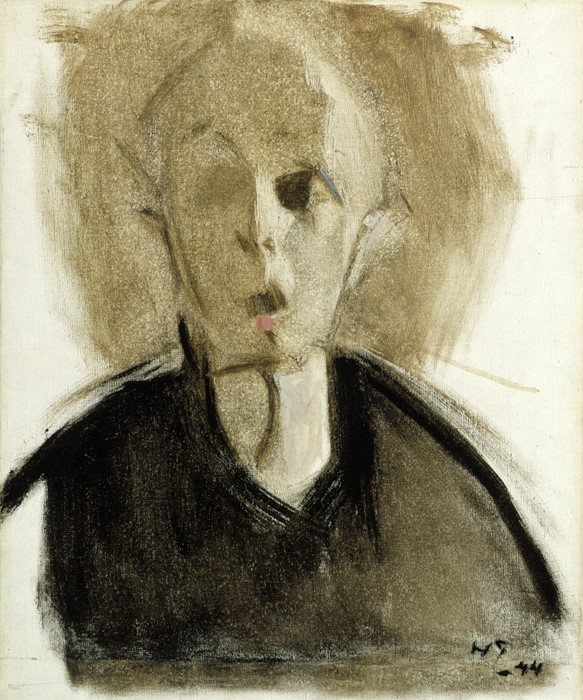

Helene Schjerfbeck, Self-Portrait with Red Spot, 1944

The canon of modernity often oversees its female contributors; only slowly is today’s institutional art world coming to appreciate and understand the significance of female painters in the late 19th and early 20th century. Central here is Finnish artist Helene Schjerfbeck, who with her melancholic colour-palette and sensitive subject matter became one of most important modern Scandinavian painters of her time. Born in 1862, she was recognised early on in her career in Paris, praised for her Realist painting – forced, tragically, to return to live with her mother due to health problems at the age of 27. Her multi-facetted oeuvre gives an incredible depiction of the depths of human emotion. Self-Portrait with Red Spot, one of the last of the 36 self-portraits she did in her lifetime, reflects the deep sense of loneliness and despair she felt towards the end of her life – hollow and increasingly skull-like, she paints richer in emotion than any of her male counterparts.

Francis Bacon - Study for Portrait , 1949

The Irish painter continued the modernist legacy of problematising the human figure in painting, and placed himself at a point of tension between psychological representation and physical abstraction. Intensely dramatic, the central point in Bacon’s Study of the Human Body from 1949 is the screaming mouth, gaping and black in an otherwise barely sketched-out face, trapped in what appears to be a cage. Bacon’s painting was often autobiographical - his troubled childhood as a refugee and later, his struggle as homosexual run as recurring narratives in his work. Despite his ‘conventional’ easel-based practice, Bacon subverted painting stylistically and thematically more efficiently than anyone else – from within. His passing in 1992 symbolised the end of an extraordinary era in painting.

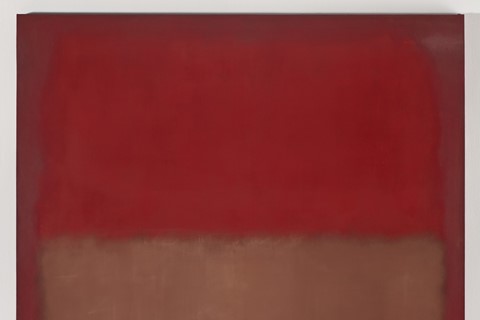

Mark Rothko's No. 46 [Black, Ochre, Red Over red], 1957

No. 46 is the epitome of American abstract expressionism, with its complete denouncing of pictorial depth and a full devotion to the study of surface and colour. The process of painting was key to Rotkho, who meditatively produced these large-scale painting in the 50's and 60's, embodying the modernist idea of the lonely, struggling artist in the studio. In No. 46, rectangles of colour almost hover above the canvas, with the endless reapplication of paint visible around the edges, signifying Rothko's desire to use painting as a ritualistic gateway to higher spiritual contemplation. Eternally troubled, Rothko dealt with alcoholism and drug abuse for long periods in his live, to finally be found dead in his studio, over-dosed on anti-depressants in 1970 – days after finishing the iconic Seagram Murals that are housed today at the Tate.

Keys to a Passion is at Fondation Louis Vuitton until July 6.