More than a century after foot binding was banned in China, photographer Jo Farrell discusses capturing the last upholders of the tradition

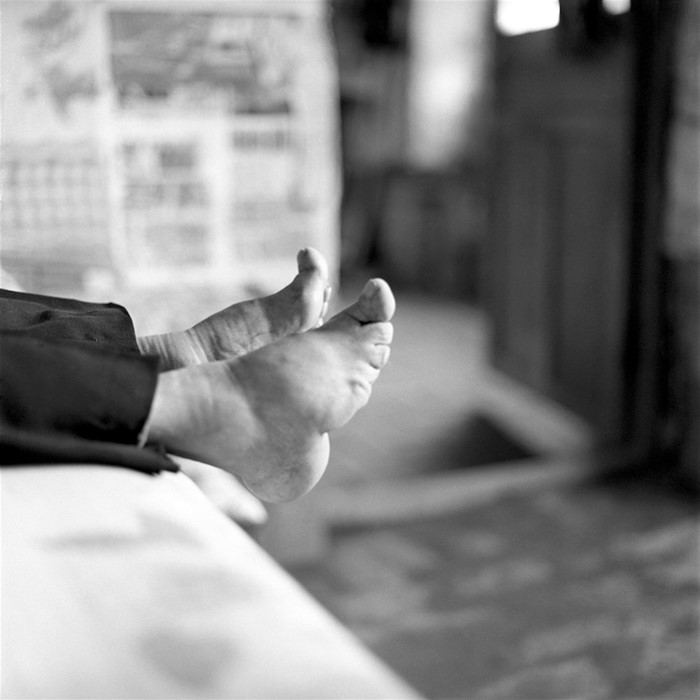

It was while reading Wild Swans, in San Francisco in 1995, that photographer and social anthropologist Jo Farrell discovered the ancient Chinese tradition of foot binding. A practice first written about in 1130AD, it involved a woman's smaller toes being wrapped under her foot, using long cotton bindings stretched around the heel, with only the big toe left untouched. After being walked upon for a period of time, the small bones in the toes would break beneath the bound woman's weight and her arches would "lift so that the heel would almost touch the metatarsals, creating a cavern." It was considered a good measure of a daughter's compliance with her parents' wishes – if she did not complain about the binding process, it was believed she would make a dutiful, obedient wife, and thus women with bound feet were more likely to marry well. Foot binding was banned in 1912 during China's period of modernisation, but continued for many years in rural areas.

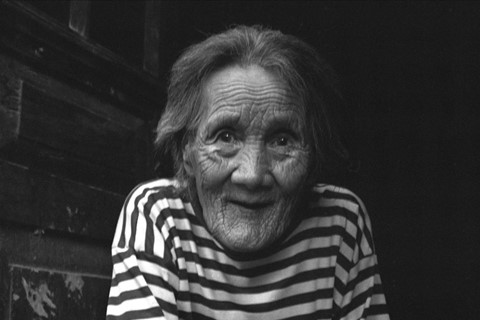

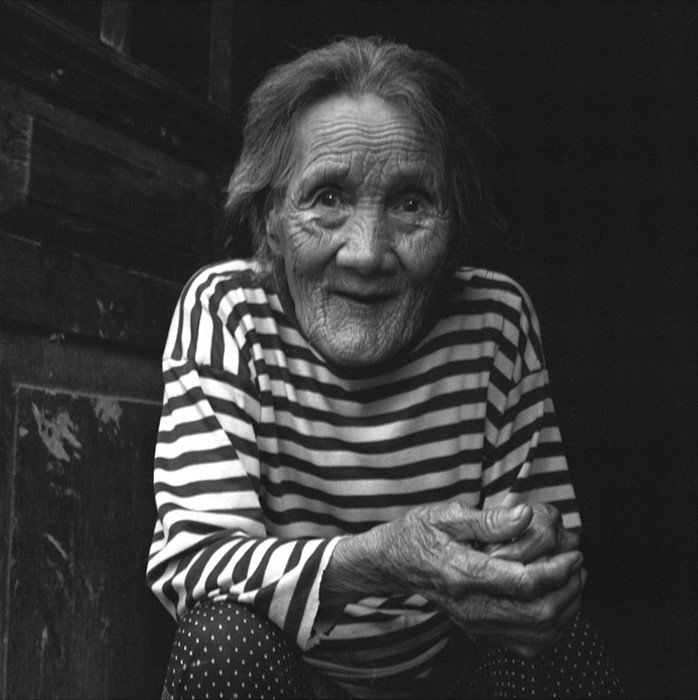

Farrell returned to the subject in 2005 when she decided that "as a woman, it would be good to document traditions and cultures of women that are dying out in different ways. And having been in and out of Asia for the past 20 years, my first thought was of foot binding." At first the Hong Kong based artist was told by various Chinese acquaintances that the tradition and its last adherents were long dead, but one day a taxi driver in Shanghai overheard her discussing the topic and informed Farrell that his grandmother had bound feet. Farrell ventured to meet the lady in question and was informed that three other women in her small, rural village had also had their feet bound, and so began a long thread of connections which led Farrell to discover more and more women to photograph – a project that she would pursue for the next nine years. Here, in celebration of the release of a beautiful book of her images, we sit down with Farrell to learn more about the project and its protagonists, alongside some of her most tender and candid shots.

On winning her sitters round...

"The first four women I met with bound feet allowed me to photograph them in person but they wouldn’t allow me to photograph their naked feet. But then I had an exhibition in London, and published a book which coincided with it, and it included a photograph of Zhan Yung Ying [the taxi driver's grandmother] sitting around and chatting with her friends. I sent them each a copy of the book, and when I saw them in the next year, they said 'I want to be part of the project. Please photograph my feet!' When I held Zhan Yung Ying's foot in my hand, it was so soft and incredibly ornate. Her feet were bound at seven years old and unbound in her 20s."

On putting bound feet back into the spotlight...

"It is very hard for the surviving women now because when they had their feet bound, it was the norm; it was considered the only way to have a better future. But they were also the generation that experienced the effects of the Cultural Revolution, where people were denouncing and shaming them for something that had been considered beautiful originally. It went from one aspect to another. So me going and saying, you are the last remaining women with bound feet and I want to tell your story – they do really appreciate it. Also they're in their 80s and 90s and they’re slightly invisible, like any old person becomes, and now they’ve suddenly been put back into the spotlight which is also quite enjoyable."

On her shifting perception of the tradition...

"I had a completely different perception of what foot binding was when I began the project – I’d always heard and read that these women were from elite families – they didn’t have to work for a living, they lived a life of luxury. But all the women in my project were from peasant families in rural areas and have worked in the fields for 50, 60 years with bound feet. Partially, like any fashion, it went through the classes, from the elite to the poorer people, and in these poorer families it was considered the only way to marry up – the mothers-in-law quite expected their future daughters-in-law to have bound feet."

On the pride and pain of having bound feet...

"All the women said the first year was excruciatingly painful, but none of them regret having it done. If you think of having to walk on your small toes until the bones are crushed then it defies pain. After that it became numb and they were retaining this beauty, and being praised for what they had done. But because they had to work so hard in the fields, most of them say they wished they'd never had bound feet. That said, most of them are now in their 80s and 90s and none of their problems have anything to do with foot binding – they’ve had cancer or a stroke or are bed-ridden."

On creating discussions between generations...

"Several of the women's children or grandchildren have never seen their feet, in fact a lot of them say nobody has ever seen their feet. When I was there in September, we went to visit my new translator's grandmother who had bound feet. She was embarrassed about asking her grandmother at first and her grandmother was a bit shy about it too but then they really got into talking about how it was done. It was very touching actually, seeing the two of them together talking about it."

Jo Farrell will speak about Living History: Bound Feet Women of China at Asia House tonight. The publication is available now.