A show at the Venice Biennale takes us on a journey through the story of street art – here we present our five graffiti highlights from World War II to now

Art or vandalism? Violent expression or expressing yourself? Basquiat or Banksy? Even in the ever contentious world of art, the heated debate surrounding graffiti is more scalding than most. So as a new show, The Bridges of Graffiti, opens in Venice to celebrate both the history of the form and the newest, most exciting voices working within it, we trace back through more than 60 years of the spray can, remembering the pioneers and tags who have shaped its story.

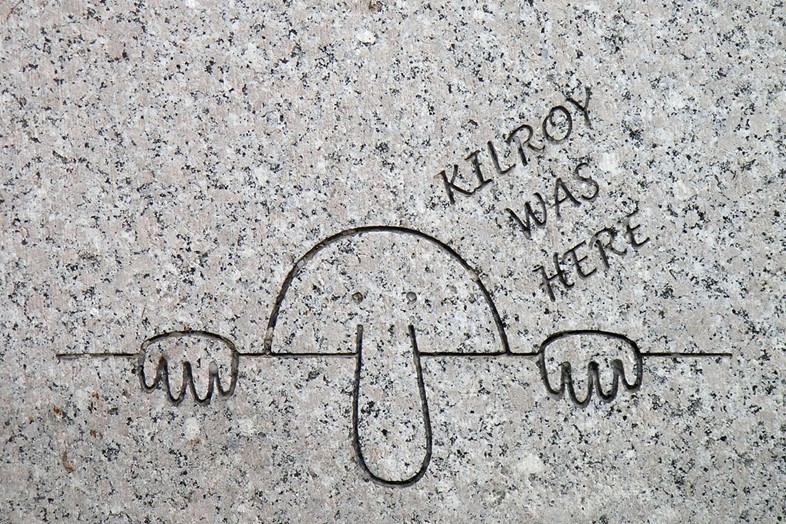

WWII: Kilroy Was Here

Graffiti had a modest beginning. Looking back, beyond its associations with New York City subways and position as a central tenet to an emerging hip-hop culture, it first came to public attention in the 1940s in the form of Kilroy – a cartoon face with a large comical nose peering from behind a wall, alongside the text ‘Kilroy Was Here’.

Throughout the 40s the popularity of this icon increased, as Kilroy became associated with American soldiers during WWII, appearing at barracks and on military equipment. The origins of its titular character was the cause of much speculation – in December 1946, the New York Times ran an article on the emblem, trying to attribute it to the spraycan of a shipyard employee who was using ‘Kilroy Was Here’ as a means of proving to his employers that Mr Kilroy had performed his duties. No one really knows but the image of Kilroy was so prolific it became a transatlantic phenomenon, taking on the name of Mr Chad in the UK, but from the 1950s the appearance of this graphic icon lessened as more diverse forms graffiti started to appear.

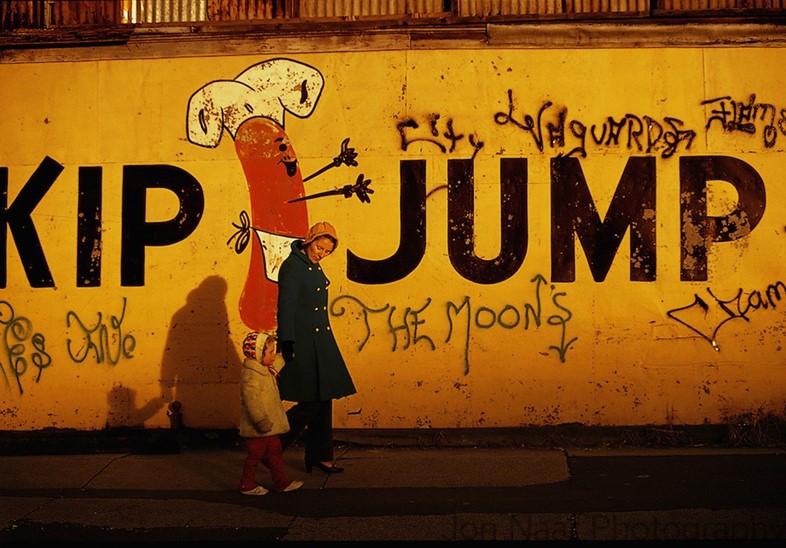

1960s New York Beginnings

In New York, TAKI183 started appearing on subway cars from 1971. It was the abbreviation of the writer’s name – Demetraki – and his address, 183rd Street in Washington Heights. Taki was 17 at the time the article was published and had been working as a foot messenger, a job which gave him access to subway cars and streets all over New York City. The trend proliferated, and in 1974, Norman Mailer wrote an essay titled The Faith of Graffiti, published in book form alongside images by Jon Naar, in which he aligned the likes of CAY161 and TAKI183 with Giotto and Michelangelo, de Kooning and Rauschenberg – “What a quintessential marriage of cool and style to write your name in giant separate living letters, large as animals, lithe as snakes, mysterious as Arabic and Chinese curls of alphabet.”

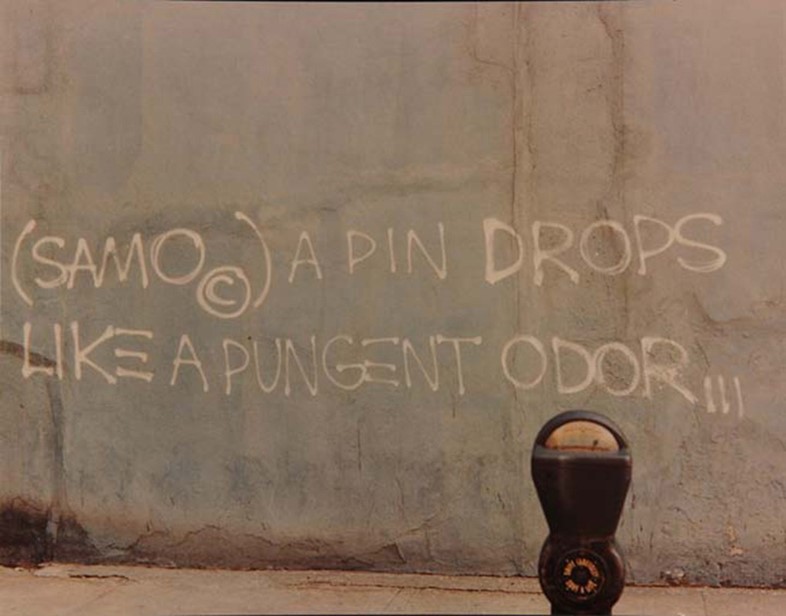

1980s boom

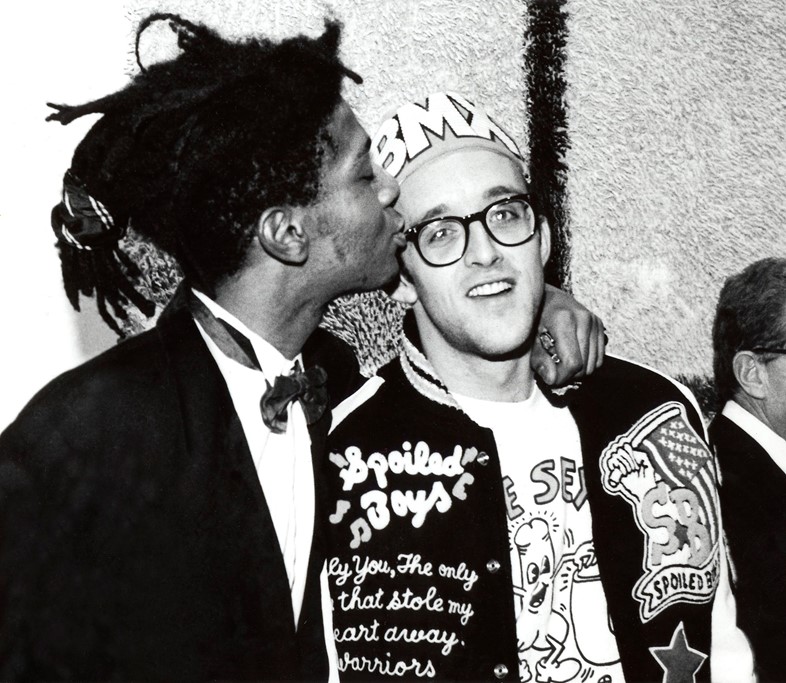

The graffiti boom during the 1980s is mostly thought of as a countercultural phenomenon synonymous with the New York City subways and streets. Born in New York in 1960, Jean-Michel Basquiat began inscribing SAMO© on buildings in Lower Manhattan from as early as 1976. The tag, which Basquiat said emerged from a stoned conversation with his friend and collaborator Al Diaz talking about the marijuana they were smoking being “the same old shit”, caught on, and evolved into longer, more poetic sentences. But in 1979, after an altercation between Diaz and Basquiat, Basquiat started to write ‘SAMO IS DEAD’ signalling the end of the principal movement. By the 1980s his solo work had been exhibited in galleries and museums across the globe. Yet, regardless of its location, whether on the street or in the gallery, Basquiat’s art continued to critique social systems and power structures, with art critic Jeffrey Deitch describing Basquiat’s work as “disjointed street poetry.”

Another key practitioner in the New York graffiti movement was Keith Haring who, after meeting Basquiat in 1979, started to draw white-chalk pictures on the plain black paper pasted over old ads in subway stations. By 1984 Haring was invited to create a temporary mural for the National Gallery of Victoria and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Arts. His boldly drawn and vividly coloured figures are easily recognisable and tackled subjects such as sexuality, AIDS and war. During the 1980s there were a number of exhibitions devoted to this energetic art movement. Washington Project for the Arts held an exhibition entitled Street Works in 1981 and in 1984 Francesca Alinovi curated the exhibition of New York graffiti Arte di Frontiera in Italy, including the likes of Haring and Basquiat, and which its curator described as “an intermediate space between culture and nature, mass and elite.”

Banksy and his imitators

Despite being active for nearly three decades, the identity of English graffiti artist Banksy is still unknown, and much debated. His work is easily recognisable – creating stencilled murals that shrewdly satirise and critique the establishment and general complacency of society. Banksy began working in Bristol in 1990 as part of the larger Bristol underground scene and his work can now be seen in cities all over the world from Bethlehem and Philadelphia to Melbourne. He is thought to have been inspired by Parisian graffiti artist Blek le Rat, who in 1981 began to paint stencils of rats onto walls around Paris. Banksy’s work can be ambiguous as well as abrupt. In one of his more poetic pieces a young girl releases a red heart shaped balloon and she watches as it starts to drift away whilst his more literal approach can be seen in the “We’re Bored of Fish” which was painted in the penguin enclosure at London Zoo. Banksy has become enormously commercially successful – one of his works sold for £288,000 in 2007 – and his rise has seen innumerable imitators as well as a conversation begin in earnest about the value and ownership of street art.

The Bridges of Graffiti

Thirty years on from the Arte di Frontiera exhibition in Italy, a new exhibition titled The Bridges of Graffiti at the 2015 Venice Biennale positions itself as the sequel to the 1984 show. As well as a section dedicated to the history of the art form, ten international artists including Doze Green, Eron and Futura have created new works and collaborated to produce a Hall of Fame piece. Self-taught artist Todd James, also known as REAS, contributes vivid, amusing yet disturbing musings on themes that range across war, sexual exposure and capitalism. Time Waits For No One is strikingly similar in style to a Matisse cut-out, featuring four faceless figures and disembodied hands lurching from inside the work brandishing large guns. Meanwhile the graphic flourishes of Mode 2 fill a large wall with a mural that draws powerful influences from a childhood spent immersed in science fiction literature and comic books.

The Bridges of Graffiti not only references the long and energetic history of graffiti but also its future. Whether the works appear inside in an exhibition or on the street, they continue to enrapture their audience because of the ever-evolving relevance of street art and its unrivalled ability to speak to the masses. Due to the distinct style of all its practitioners, it is a varied and fragmented cultural phenomenon that, like any contemporary art form, continues to negotiate its own parameters and boundaries.

The Bridges of Graffiti is at Arterminal c/o Terminal S. Basilio, Fondamenta Zattere Ponte di Legno, Venice, until November 22.