New exhibition The World Goes Pop is subverting the familiar language of pop art, with a look at some of its lesser-known pioneers

A product of its own reputation, the genre of pop art has come to be represented by just a few iconic images; Warhol’s Campell’s Soup Cans, for example, which are now emblematic of 1960s New York, or Roy Lichtenstein’s poignant half-tone flecked kiss, reproduced so many times as to feel like a simulacrum. Beyond the coffee table publications and the copycats, however, these pieces sit within a rich and diverse cultural context – one which spreads far beyond the perceived pop boundaries of North America and Great Britain, originating instead in continents as diverse as Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

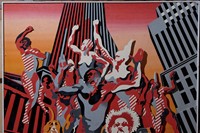

This alternative history of pop, one which distances itself from a wry criticism of Western consumerism and instead forms a mouthpiece for contentious subjects around the world, is the subject of Tate Modern’s new exhibition, The World Goes Pop. The collection of artworks included in the show is comfortingly familiar-looking on first glance – indeed the first and last rooms of the show bookend the collection with Equipo Crónica and Komar and Melamid’s appropriations of those aforementioned pop masters. This is a deeper exploration though, broaching subjects from the Cold War and propaganda in the media, to the domestic structure and the eroticisation of the female body, and it’s all the stronger for it.

Detailed depictions of the biological body quickly emerge as a recurring motif in the exhibition, presenting ideas about interiority in new and unexpectedly powerful ways. This is especially true of the women’s liberation movement, to which one of the largest rooms in the exhibition is dedicated. “Pop’s comic-book blondes and advertising models have become familiar images of the idealised female body,” the gallery explains, “but this exhibition also reveals the many women artists who presented alternative visions. The pop body could be complex and and visceral instead, from Brazilian Anna María Maiolino’s isolated body parts by Slovakia’s Jana Žeblinská and Argentina’s Delia Cancela.”

Similarly, war-related artefacts such as retired missiles are re-clothed in hippy paints and textiles, as in the case of both Kiki Kogelnik’s Bombs in Love and Colin Self’s gaudy Leopardskin Nuclear Bomb No. 2. The effect is to propel these once terrible objects far beyond their intended purpose, pulling the rug out from under atrocities like the Cold War and Vietnam and satirising the decisions which caused them. An unexpected use of the pop art motif, these pieces are paradigmatic of the genre as an “overtly political, destabilising force,” as the gallery describes it. “[The exhibition] shows how artists used this visual language to critique its capitalist origins, while benefiting from its mass appeal and graphic power.”

Around the works, walls have been painted to extrapolate overwhelmingly vibrant colours from the collection onto its surroundings, making the exhibition an immersive, almost inescapable experience, which climaxes with the wallpaper made from Thomas Bayrle’s The Laughing Cow in the final room. “Advertising always shows consumption as pleasurable. Many works here show the coercion which backs it up.” A broad and cohesive collection, The World Goes Pop brings together disparate artists to shine a spotlight on those who’ve long dodged the mainstream, preferring to start revolutions in the movement’s periphery.

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop runs at Tate Modern from September 17 until January 24, 2016.