The award-winning filmmaker explores unchartered depths with her immersive new underwater installation

The pitch-black subterranean cavern of an ex-concrete testing facility in Marylebone, London, seems a suitably vast, yet claustrophobic space for a multi-screen underwater film installation by the Italian born, BAFTA-winning film maker and free diver, Martina Amati. The exhibition UNDER, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust, charts the three disciplines of free diving, a sport which captivated Amati from a young age through her affinity with water and a love for the mental agility required to dive to uncharted depths attached to a single cord, on a single breath.

The first discipline involves statically holding one’s breath, often in a pool, so all factors and forces can be tightly controlled to make for optimum conditions. The current world record for a static breath hold in a pool is just over 11 minutes. A video explores this phenomenon with shots of professionals in training – lucid bodies in wetsuits that appear suspended in transparency. It seems ghostly and lonely, yet watching the divers bob in the water, pulses slowed right down and limbs hanging loosely, is eerily contemplative.

The second is concerned with length – swimming horizontally along a rope and through underwater caves and tunnels. A large vertical screen shows silhouetted figures clad in wetsuits and sometimes wearing a mono-fin, causing them to look like an aquatic-mammal hybrid – like a ironic primordial devolution of human form that's better suited to living in water. The divers follow a guideline down, then along – they look like gravity defying tightrope walkers set in slow motion. A constantly shifting camera orientation flickers on the horizon – top and bottom shift and it soon becomes hard to tell if it is the divers who are upside down, or you.

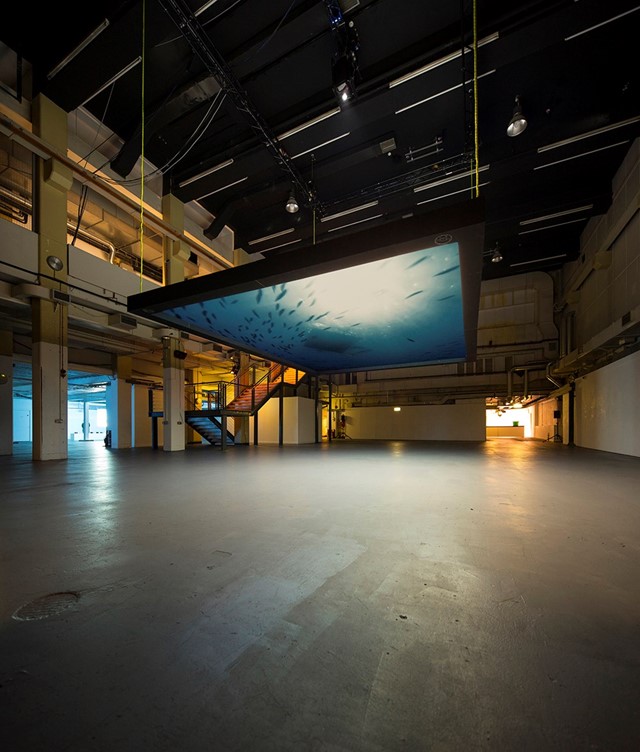

The final facet of free diving, which is most commonly known and really sparks the imagination, is depth diving. Different levels of purists measure world records according to varying equipment allowances and conditions, but the current record, depending on whom you ask, is anything from 100, to a staggering 283 metres, all on a single breath. A huge video screen documenting vertical depth diving is suspended from the ceiling horizontally on four diving guidelines, but only feet above the ground. As you move at a parallel underneath it, neck craned up, you at once feel yourself as submerged as the divers in the film – swimming deeper and deeper with nothing to hear but the water rush past the ears, descending into a foreign abyss. It’s a sensory overload – exhausting and alien, but completely riveting. The size and position of the screen make it impossible to take in with one glance – the work completely wraps around you. It takes “immersive” to a whole new level.

Filming underwater came with many challenges Amati said – firstly the camera man had to be a free diver themselves in order to accompany the film's participants in the same manner. Secondly the equipment causes buoyancy issues – when diving down, the first part of the journey must be swam, but once you reach 20 metres, the lungs are compressed enough that you naturally begin to sink. Adding the weight of waterproof recording equipment caused problems with the natural ascension and descension of the divers. Finally, colour saturation was an issue, as past varying depths certain rays of the colour-spectrum can’t penetrate the water. After ten metres you lose sight of green, after 20, red, and by 50 everything appears like a muted slow moving apparition against an infinity of blue-black.

Martina Amati’s love for the water and the sport is always apparent – from her shark tooth necklace and her diver’s watch, to the way her eyes light up when she talks about water – even her whole demeanour is fluid. But it’s an obsession that seems to be full of reverence and respect. “While submerged you can’t pretend to be anything you’re not,” she explains. “It’s just as mental as it is physical, and in the water you have to be completely true to yourself." It’s clear that free diving is extremely meditative, both in and out of the water – intense training of the body and the mind is required as you’re physically denying your body the very oxygen it needs to live. Once submerged, everything is about focus. In August 2015 a world-champion female free diver from Russia didn’t resurface, and black outs due to rising nitrogen levels in the body are frequent.

During the turbulence of her life, Amati has found solace in the depths of open water – a place that to many seems anxious, to Amati, is spiritual. UNDER helps explain this esoteric nature of the sport – after seeing the world of free diving through Amati’s personal lense, the poetry of submersion becomes instantly recognisable. The three films work in a brilliant cohesion and are dazzlingly beautiful and transfixing. Through Amati’s work, the vastness becomes warm, the divers become a community and the movements become dances. Underwater, time, space and all your worldly problems cease to matter – the only focus is on the self, in that single moment of immersed suspension.

UNDER by Martini Amati at Ambika P3, 26 September – 11 October 2015.