As the British art star's explosive new show opens at the Barbican Centre, we revisit this in-depth preview of the project from the A/W15 edition of AnOther Magazine

A dark-haired woman is dancing from foot to foot, swinging her arms, swaggering and spitting, nude but for a pair of black Nikes, on the Mac monitor in Eddie Peake’s Hackney Wick studio. We’re watching documentation of his performance work, The Labia, staged earlier this year at the Lorcan O’Neill Gallery in Rome. The sound isn’t great (it was echoey) so Peake fills in: “She’s saying ‘Oh! Make me some space!’” The Italian-English dancer-actress Claudia Palazzo is playing one of the archetypal figures he likes to mess with: a Romano, a kind of Roman wide boy, who Peake compares to an East End Cockney. “All words end in an ‘oh!’ sound,” he says. For a moment, as he runs through the Italian lines perfectly in sync with his performer, copying the ballsy body language that he’s clearly rehearsed move for move many times, he’s no longer the gentlemanly young artist hosting a writer on a studio visit. Instead he’s in character, fully immersed, and there’s a glimpse of the drive and focus behind what, by any standard, has been a fast-paced art-world ascent.

At first sight though, it’s unlikely you’d take Peake for an artist at all. Younger looking than his 33 years, he’s dressed in the uniform of the average, streetwise, London every-lad: sportswear, a hooded jacket in the colours of the Italian flag, a little gold earring in each ear and with his hair shaved close. He might be heading off to a game of footie in the park. His accent is 21st century North London, its halting cadences shaped by diverse ethnicities and urban music, and though highly articulate, he often pronounces long words slowly and carefully, as if to underline his distance from the language of an intellectual elite.

Within a contemporary art landscape that can often seem cut off from the currents of daily life, Peake’s shows – combining painting, sculpture, video and performance – have been quite a wake-up call over the past four years. Signature works include spray-painted and stencilled canvasses and mirrors, depicting smiley faces and slang that recall graffiti scrawls and streetwear logos; silhouette sculptures of cartoonish figures in slivers of marble and brightly coloured painted Perspex; and, most famously, performances, typically nude, though a furry tiger costume or a pair of roller-skates is not to be unexpected.

Peake turned heads with a game of naked football staged in 2012, while a postgraduate student at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. It had “brash energy, a wit and beautiful absurdity” and was “discussed at length across all departments”, according to Senior Tutor Brian Griffiths, who remembers Peake as “a big part of the intense conversations and great alliances within an exceptionally exciting and complicated year group”. What really made art’s aficionados pay attention, though, is his luxuriously sexy series of works, where black-and-white male and female dancers mix classical poses with music video routines to live soundtracks. They’re a heady fusion of timeless beauty and erotic charge, art history and a big juicy dose of urban pop that feels so "now" it practically fizzes on the tongue.

A few stand-out moments in this seduction of the art world would include his debut 2013 show at London’s prestigious gallery, White Cube, which made him the first young Brit snapped up in years by the operation famed for championing the YBAs. Within a curvy structure inspired by the modernist penguin enclosure at London Zoo, Peake choreographed a gang of exotically naked humans, including himself and, most memorably, a roller-skating guy in a see-through white onesie.

Later that year in New York, his performance Endymion was the glittering highlight of the landmark Performa festival. Men and women painted all over in bright toffee-wrapper gold or dense midnight black moved through a series of static poses, casual gestures and synchronised dance routines to eerie, slowly building electronica. Named after the ancient Greek legend about the beautiful shepherd Endymion, whose sleeping body so entranced the moon goddess Selene that she asked Zeus to keep him asleep for eternity – a scene captured in all its soft, seductive glory by the neo-classical painter Girodet – Peake’s creation was no less tantalising in its blend of both male and female beauty and equal-opportunities physical longing.

“The big thing at play is relationships. Romantic and sexual, but also familial, professional, societal and cultural. I’m interested in their inherent trials and tribulations. It might be the experience of a relationship where somebody makes it clear they find X, Y or Z sexually stimulating and that thing is definitively not you” – Eddie Peake

“The big thing at play is relationships,” he says. “I mean romantic and sexual relationships, but also familial, professional, societal and cultural. I’m interested in their inherent trials and tribulations, whether that’s one-to-one or a broader, societal thing. It might be the experience of finding someone attractive who doesn’t find you attractive back, or being in a relationship where somebody makes it clear that they find X, Y or Z sexually stimulating and that thing is definitively not you.”

Speaking about how the performances “focus our gaze on the body as a sculptural and sexual object, an object of voyeuristic desire”, Alona Pardo, the curator of Peake’s forthcoming show this autumn at the Barbican’s Curve gallery, tells me, “I would even go so far as to say that ‘desire’ is key to reading Eddie’s work. He fully admits to being drawn to sexual imagery, but what I find most interesting is that his representation of the body with all its imperfections is an honest one and frequently implicates himself.”

Though toned, professional dancers are regular collaborators in performances that require total fluency in body language, not to mention the right libidinal throb, Peake himself is no bystander. “He is often in his own images, and indeed he candidly appears with an erection in a number of his early photographs,” adds Pardo, referring to the graphic shoot used on his website. (“The response I often get is that it’s not very office friendly,” he said in our first interview a few years ago.)

Much has been made of Peake’s use of the male body, not least as an artist who has a girlfriend – the painter Celia Hempton, whom he met during a residency at the British School in Rome from 2008 to 2009. Like his work, he ducks obvious sexual categories and doesn’t describe himself as straight. “At the moment, it seems to me that male sexualised nudity is a sort of weird eccentricity, uninteresting to most, owned emphatically by gay men,” he reflects. “I’m not saying it should not belong to gay men, or anyone else for that matter. I’ve been accused of usurping male homosexuality through my depictions of the male nude. That’s always felt weird to me because I’m just naturally riffing on my own impulses, as opposed to calculatedly trying to make something that looks this way or that. So yeah, erections, masturbation, dicks being sucked, I love all that type of imagery.”

Yet though his study of the push and pull of human attraction is often seriously steamy, perhaps what really zings with the shock of the new is Peake’s address to contemporary life. It’s hard to think of another artist whose work tackles what he calls “the real world” beyond the “art world bubble”, with the same sincere enthusiasm. “I’m not looking at popular culture from a slightly snobbish meta position,” he says, reflecting on what he sees as its standard treatment in art. “No way. I want to be in that world too.”

While top international dealers and curators have come calling, he’s been busy blurring boundaries both on and off the art world’s usual stage. For his post-graduate show at the Royal Academy two years ago, he invited Kool FM, the former pirate radio station that provided the jungle soundtrack to his formative years, to record a live show within the RA’s antiquated halls. Meanwhile, beyond gallery confines, he stages the cult gay club night Anal House Meltdown with fellow RA alumni Prem Sahib and the artist George Henry Longly. This year he set up his own record label, Hymn, and created his first music video for his frequent performance collaborator and one of indie pop’s most committed experimenters, Gwilym Gold. He’s even starred in a music video himself, for no lesser a pop culture titan than rap’s reigning wordsmith, Kendrick Lamar, shot in Los Angeles by one of his collectors, the director Darren Romanelli. All while managing an art career that, since his graduation, has progressed at workaholic speed through an average of three international solo exhibitions a year.

We’ve met in mid-June, a few months before his take-over of the Barbican’s Curve. Things are still in progress, though he explains the whole exhibition will be structured around the idea of the loop, with an all-nude live performance and video work weaving in and out of sync with each other, overseen by an audience on an aerial walkway. “One reason that I love the art gallery specifically as a venue for performance is that the viewer is as much on display as the work,” he points out. “Looking at a covetously desirable sexual body inevitably has to become part of the subject matter. You’re as vulnerable as the performer if not more so.”

All kinds of exposure is going on in Peake’s art – of bodies, desires, emotions, be they ours, his performers’ or his own. At the same time, his works often suggest how hard it is to communicate at all, to breach the gap between one mind and another. There’s a contradiction, for instance, in his use of airy, depthless spray paint or his stencilled cartoon sculptures, which might seem breezily upbeat and impenetrable in their flatness, and their often loaded genesis and titles. For Peake, these poker-faced creations are “characters in an ongoing drama”, but one plotted along intimate lines.

Recent additions to his series of acid smiley-face paintings, created by stencilling scarves and bags against squiggly spraypainted backdrops are, he says, related to his time in a psychiatric hospital when he was 20. Their titles, Giving Herself A Caesarian Section, 1 to 10, refer to a woman he met there, who “seemed on the surface to be quite normal, but told me she’d given herself a Caesarian section on a hunch that she was pregnant, without actually having had penetrative sex”.

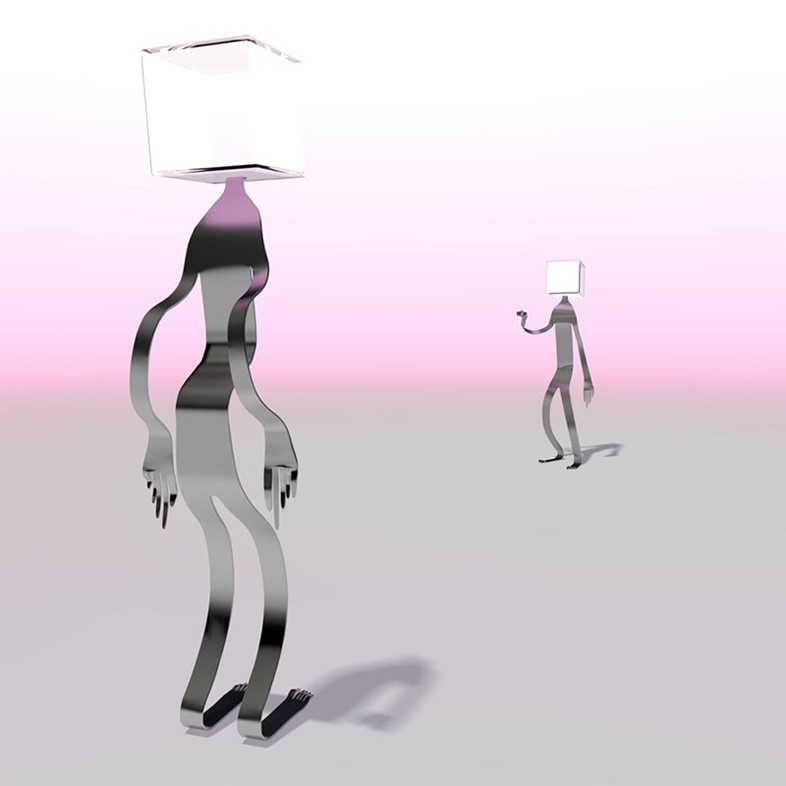

New sculptures of wibbly-wobbly paper-thin men crowned with clear box heads filled with junk, were partly inspired by one of his favourite films, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, where the villain is steamrollered, only to become a flat yet more evil cartoon. There’s an edge to his wry spin on 2D illusions and 3D bodies, however. The transparent boxes, Peake explains, contain his old diaries. “They’re full of my most indulgent angst and so embarrassing, I wanted to burn them so that no one, including me, would ever be able to read them, but I couldn’t quite bring myself to do that.” Now they’re unreadable in a sealed sculpture, accompanied by such items as “knives I have used in the past to cut myself”.

Peake might make creative use of his personal history, but that doesn’t mean nothing is off limits. In his studio he unwraps a new sculpture of a cross section of whalebone in bright red rubber, destined for the Barbican show. The original whalebone, browning and prehistoric-looking, is also there. He used it in his music video for Gwilym Gold’s Muscle, which featured a nude woman, the whalebone and a kitten on display in a glass-walled office. He’s drawn to its sheer oddity, he says, which particularly hit home when he found a kitten curled up on it, in his parents’ home. That they had this artefact at all is the stuff of family legend: his grandfather had found the whale carcass washed up on a beach, removed the bones and given them to his children. Yet his grandfather isn’t something he’ll talk about. The same goes for his parents.

“I love the immediacy and aggressiveness slang can possess, as well as the fact it can be quite alienating. The phrases I use tend to be drawn from my surroundings, things my friends and I would use or hear growing up in the 90s. It’s a language that indicates a certain social and ethnic cultural diversity, which I didn’t hear in the art world” – Eddie Peake

The reticence is perhaps less strange than it sounds. Though keen to break out of high art’s ivory tower, Peake himself comes from a prestigious creative lineage. His grandfather is Mervyn Peake, the author of the trilogy of fantasy novels, Gormenghast; his father Fabian Peake is an artist and writer; while his mother is Phyllida Barlow, the British sculptor whose career has crescendoed alongside her son’s, after many years working as the much revered Professor of Fine Art at the Slade School, where Peake first studied. His apparent refusal to ride any coattails is understandable.

The artist’s upbringing in multicultural Finsbury Park in North London within an “an emphatic matriarchy, surrounded as I was by four massive older female personalities” – his mum and three sisters – is something he has plenty to say about, however. Eight years his senior, his sister Florence is a respected dance artist who appeared in one of his early works, Ciao, made with Paul Simon Richards in 2010. Clover is a poet whose lines have complemented a number of his shows in place of the usual press release artspeak. Tabitha, the middle child, is a nurse specialising in HIV treatment, whom he describes as “the glue of the family”. His younger brother, Lewis, designed his animal silhouettes and other cartoon-ish works.

As a child, his sisters’ love of Kate Bush, Madonna, Prince and Eurythmics was his first introduction to music. Discovering the 1990s jungle scene in his teens was a decisive moment, though. “I was hooked on that sound,” he recalls. “I love the way jungle is constructed by using samples – a James Brown drumbeat, a Buju Banton or Mary J Blige vocal, a Star Wars sample. Yet you experience it is as a unified, distinct aesthetic. I hope that echoes something about the way I work.”

For Peake it also had a political aspect that came to light when he went to art school. “At the jungle raves I went to many times as a teenager, you would see this rainbow of cultures, because it was a London sound,” he says. “Art college was very white and middle class. A lot of my work laments that filtering out of diversity.”

Peake’s earliest offerings with body-beautiful performers are usually discussed in terms of gender. In 2011, the series debut, Contrapposto Pause, at the Bermondsey project space V22, set the tone with an all-male cast in figure-hugging sportswear, working through the limbering-up moves of football players and dancers, before standing as one in the casual contrapposto pose of Michelangelo’s David. This led to Amidst A Sea Of Flailing High Heels And Cooking Utensils, an orgiastic floorshow of both sexes with dramatic stage lighting and smoke machines, part of a monumental programme that christened Tate Modern’s performance-dedicated series, The Tanks: Live, the following year while Peake was still studying. His performances, though, are also emphatically colour-blind.

Even the slang that he sometimes uses in his text paintings, which veers from abrasive toilet-door graffiti (Grrls Who Love Dick) to party shout-outs (Cllng All Rvrs; Deafening Bassline), harks back to his commitment to inclusivity. “I love the immediacy and aggressiveness that slang can possess, as well as the fact that it can be quite alienating,” he says. “The phrases I use tend to be drawn from my immediate surroundings, things my friends and I would use or hear around us, growing up in the 90s. It’s a language that indicates a certain kind of social and ethnic cultural diversity, which I didn’t hear in the art world and academia.”

Over the next few months, Peake’s typically break-neck schedule includes exhibitions from London to Hong Kong, a new animated video for Gold, and the first release of his own music, made with the Anal House Meltdown posse. (“It’s banging techno. Very much played to be experienced in a club with a loud sound system.”) And while he dreams of making a feature film one day, that doesn’t mean he’s about to abandon his first passion. “I love art,” he affirms, “I just don’t love the art world.” Besides, he says, “I don’t have a line between my art practice and my other life. For me, it’s just what I do.”

The Forever Loop opens today at The Curve, Barbican Centre. This article appears in the A/W15 edition of AnOther Magazine.