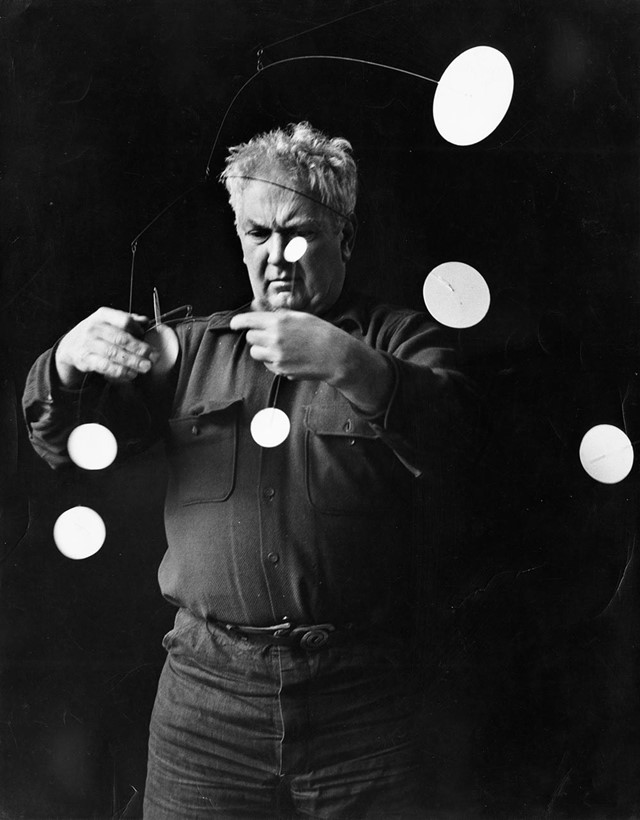

As a vast survey of his work opens at the Tate Modern, we celebrate the artist who wooed the world (Albert Einstein included) with his bold, balletic mobiles

Who? When Alexander Calder moved to Paris from New York in 1926, he found himself at the centre of Parisian inter-war bohemia, counting Joan Mirò, Marcel Duchamp, Martha Graham, and modernist composers Edgard Varèse and John Cage among his friends. “There was a very intense dialogue between the Parisian intelligentsia,” Tate Modern's Assistant Curator Vassilis Oikonomopoulos tells AnOther. “The pioneering figures of 20th century modernism were constantly with one another: sharing studios, homes, working during the day and drinking at night.

It was during this time that Calder developed his wire sculptures, defined by critics as 'drawing in space': these included portraits of tennis player Helen Wills, cabaret star Josephine Baker and fellow artists Joan Mirò and Fernand Léger. Fascinated by performance art and by the circus in particular, he created Cirque Calder: a series of small, lightweight wire figurines that he employed to stage live performances, very popular with the French avant-garde (Jean Cocteau and Piet Mondrian were fans). Some even took part in the performance, by making sounds or playing music. “It was a very convivial environment, but also a strong intellectual exchange,” continues Oikonomopoulos. “They were really thinking about the possibility of form, the use of colour, about creating things that were not conventional... they were Mirò, Duchamp, Léger, Le Corbousier: people that represented not only specific movements and types of practice, but also were really pioneering modernists.”

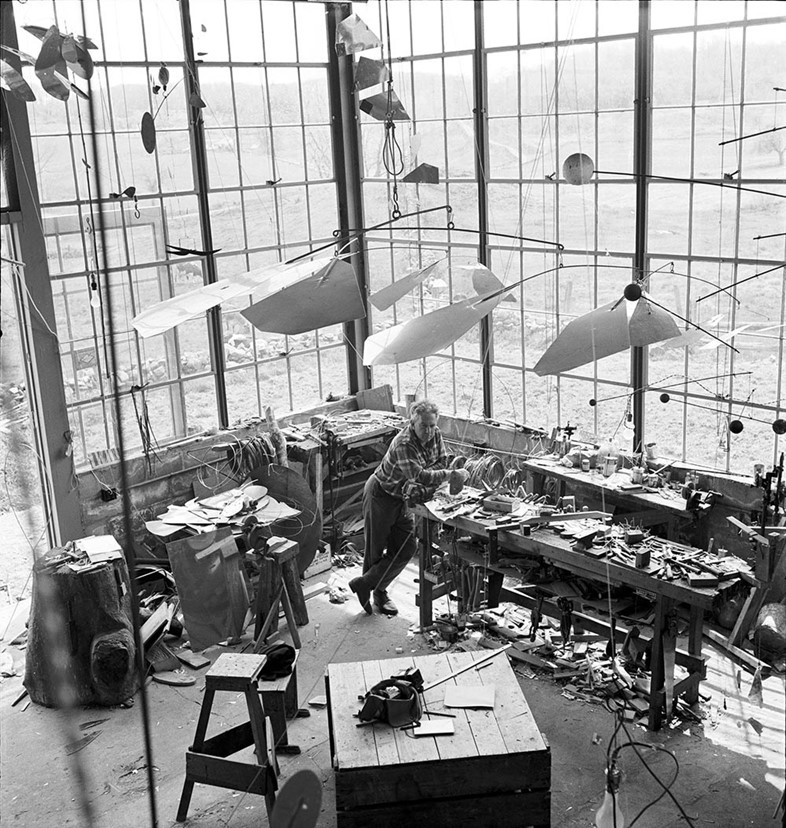

What? In 1930 Calder paid a visit to Piet Mondrian's studio and, completely fascinated by his paintings, suggested it would be interesting to make its geometrical elements move around: Mondrian disagreed, but Calder was so impressed that he even took up abstract painting for a short while. As a result of the visit, his own pieces took a more abstract form, with the introduction of geometrical shapes and primary colours. He pursued his quest to make the abstract language move in the three-dimensional space by finding new ways to animate his sculptures: from letting them hang from the ceiling and allowing them free motion, to actioning them with a small motor device. Of the latter type is A Universe (1934), at which Albert Einstein allegedly stared for 40 minutes when it was first exhibited at MOMA. Calder's moving sculptures were named mobile by Marcel Duchamp: they were no longer static objects, but dynamic and ever-changing pieces. One of the highlights of the show is a group of panel works from the late 1930s (some of which have not been seen since 1937) that testify to a brief period Calder spent experimenting with backgrounds for his pieces.

Why? Calder's pioneering approach to sculpture, which he saw as kinetic abstraction, was integral to the evolution of modernism. He recognised that there is an intrinsic performance element in sculpture, to which the viewer becomes part of when they are forced to move around it or choose a certain angle to admire it from. Calder then pushed these boundaries furhter, initially by giving movement to his pieces, and eventually by creating work that included sculpture, installation, musical instruments and dance performance. For Martha Graham, he created two pieces around which she based her performances Horizons (1936) and Panorama (1937): “Calder's mobiles functioned not only as a backdrop, but the dancer also followed their movement,” says Oikonomopoulos. “What the audience would see was the dancer responding to the way the mobile moved, and that always changed”.

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture opens at the Tate Modern on November 11, 2015.