The Scottish artist talks to AnOther about her latest works – including a melted meteorite space mission and a candle fragranced with planetary scents

To say that somebody's imagination knows no bounds is a bold proclamation, but in the case of Scottish conceptual artist Katie Paterson, it is almost an understatement. Her works call on sophisticated technologies and the expertise of scientists around the world to probe at the relationship between humans and the natural environment, to profoundly poetic effect.

Vatnajökull (the sound of) (2007) – the Slade degree show piece that launched Paterson's career – invited visitors to call a mobile number, displayed on the gallery wall, which rang through to a live broadcast of the sound of a glacier melting. Her 2011 collaboration with AnOther Magazine and Haunch of Venison Gallery saw 3,216 pieces of confetti – whose colours matched those of the 3,216 gamma-ray bursts that had occurred to date – launched from a handheld cannon at various locations during the Venice Biennale. She has mapped out the universe's dead stars; made a record player that rotates in synchronisation with the earth; and collated hundreds of thousands of images of darkness from different periods and places in the history of time into an exisitential series of slides.

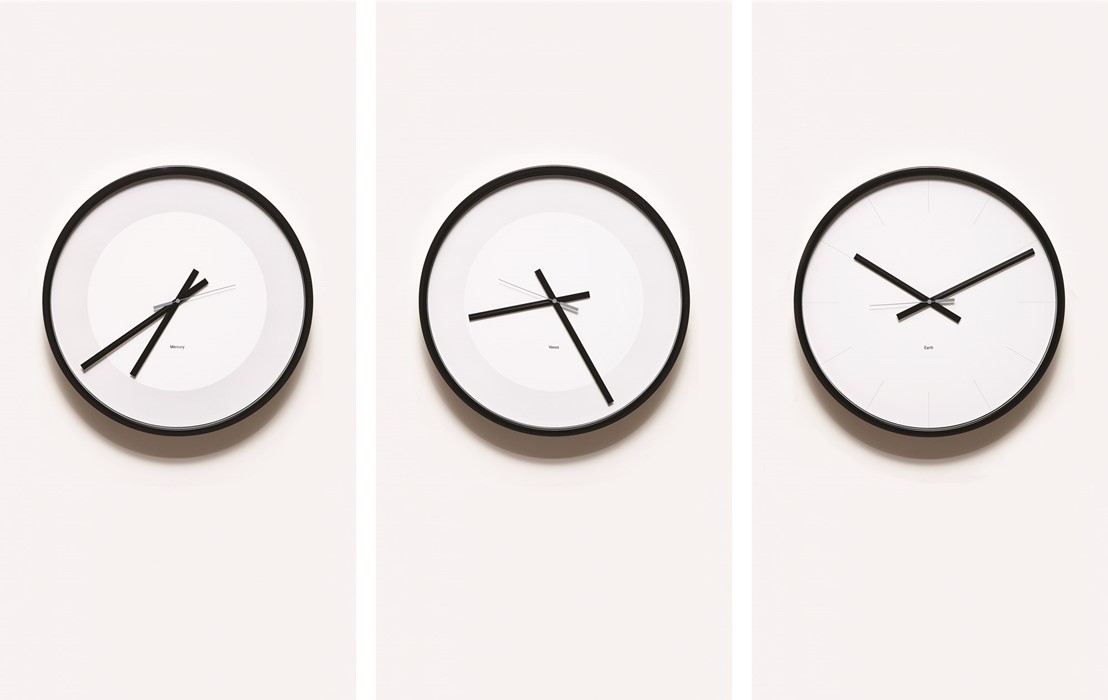

One might think that after years of plumbing the depths of her imagination, that the well might be beginning to run dry, but if anything, Paterson's potential for starry skied thinking is burgeoning – aided by her ever expanding knowledge of astronomy, technology and geology. "I’ve learned so much over these last years," she tells AnOther, "and this has definitely expanded my imagination, allowing me to go further and further into the depths of space and time. It really boggles my mind but it keeps it active." At last month's lauded art fair Artissima, for example, the artist displayed two recent, and remarkable works with Parafin gallery, titled Timepieces and Campo del Cielo, Field of the Sky. The former is a series of nine clocks that tell the time on all the planets in our solar system, including Earth's moon; the latter, a four and a half billion year old meteorite, melted down and recast exactly into its former shape (a previous work of the same concept saw the new meteorite relaunched back into space by the European Space Agency).

And Paterson's upcoming projects are just as extrordinary. Particularly exciting, and tantilising, is Future Library (begun in 2014) whereby a thousand trees have been planted in the Nordmarka forest outside Oslo to supply paper for a special anthology of books to be printed in 100 years time. Every year up to that point, one writer will be selected to contribute a text, with the writings held in trust and unpublished. The two books to date have been penned by iconic authors Margaret Atwood and David Mitchell for a very fortunate, future generation of readers. Here, in the aftermath of Artissima, we catch up with Paterson to discover more about her past, present and future projects as well as what it takes to conjure up such monumental concepts.

On the power of collaboration...

"I love collaborating with other people. In fact, it’s become the norm now; I just can’t seem to ever work alone. The thing is that I have so many big ideas that I need help to figure out how on earth to make them happen – so I always start with lots of research and finding the people to assist in their creation. With Timepieces, I already had a few astronomers that I'd been working with before so I just went straight to them and knew they would have the answers. One of the starting points was thinking about the office style clocks that you get with the time in different cities on them. So I collaborated with a designer to get the clocks looking right and then the astronomers to ensure that they all ticked at the right times. Saturn has almost five and a half hours in a day for example, while Venus has four thousand hours so that was by far the most difficult!"

On melting a meteorite and launching it back into the stratosphere...

"I thought that was one that was never going to happen, but eventually it did; the European Space Agency took it up in their ATV aircraft. I’m still quite surprised that it's gone – that it's really there!

The production process is complicated too – melting down a colossal meteorite, weighing about 120 kilos. The metals inside are actually the same as those that exist on Earth – the same kind of elements and materials – but obviously we hadn’t melted a meteorite before so we had to take it up to an extremely high temperature and recreate the conditions of the universe, essentially. I was interested in this kind of ancientness, taking this thing that's older than the Earth and melting it to reset the time within it, the cosmic timescale. Then by sending it back into space, it goes back to where it first came from and closes this circle of strange cosmic transformation."

On feeding her imagination...

"I was definitely a daydreamer as a child. I’m an only child as well, so I am used to disappearing into my own world. Strangely, I used to put aside time to daydream, which may be a bit odd because we're always to stop daydreaming as children, but actually for me it was important from an early age."

On where she has her best ideas...

"It really changes, because sometimes the ideas can come upon me quickly in the most ordinary situations – like on the train. But more and more over the years – and especially because I’ve got such a busy studio practice, where we're always fabricating and doing a lot of admin, I try to set aside time to work on my ideas. As I said, I used to do this as a child, but it's something really new for me as an adult – taking time to get into a really creative state of mind. I really like going away to somewhere isolated, in nature usually, even if it's just for two or three days. It really settles my mind, being by the sea or being in the mountains, and not being distracted by emails and everything else."

On her upcoming projects...

"I’m working on a new project that's launching in May next year, but I’ve been working on it for nearly two years so I'm really excited about it. It's a big public commission for the University of Bristol to mark the opening of their new Life Sciences building. I've created it in collaboration with the architect studio, Zeller and Moye, and we're producing an artwork made out of ten thousand different tree species, but that's all I can say for now."

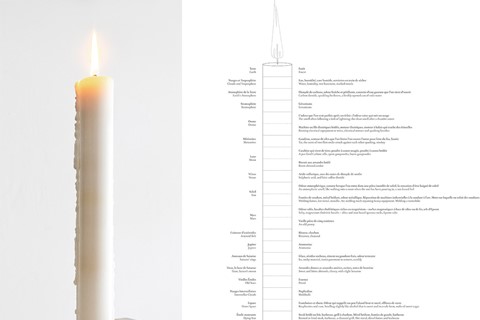

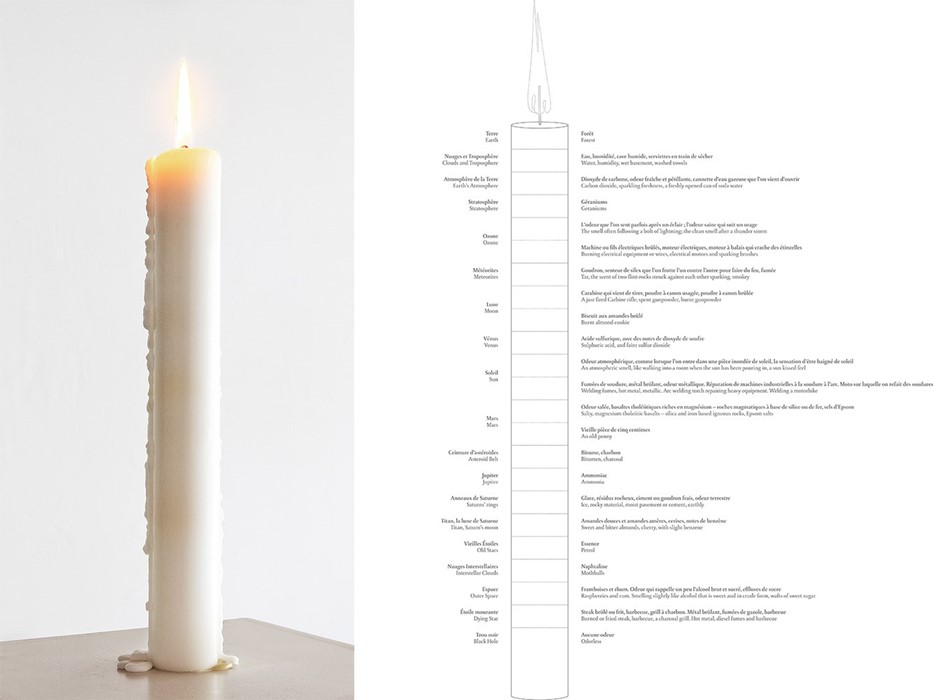

"Then there's a candle I'm making that smells like space. This is actually finished now but it still needs a bit of work –it’s been such a complicated piece. It's got twenty two different layers and every layer smells of a different planet. I worked with a biochemist on it; I came to him with a list of really specific but strange smells and we did about a year of research, looking at astronauts' descriptions of the moon, and the kind of metals that are found on Mars and so on. Like, the moon smells of burnt gunpowder and space smells like raspberries and rum, really peculiar things. Some of them are quite nasty, like phosphoric acid from Venus. The chemicals inside it are so volatile compared to anything that you might normally put in a candle so there’s been a lot of trial and error, but we're hoping we might be able to make a large production of it eventually."