Photojournalism is an agent for change. It has the power to spark crucial international dialogues, causing a catalyst of collective awareness for situations that would otherwise go unnoticed – and therefore unresolved. It’s a medium best utilised by the prolific Italian photographer, Paolo Pellegrin – whose startling and intensive human reportage has seen him navigate many of the world’s most war-torn areas of conflict, in the hopes of shedding truth and light on pandemics and crises.

“My core interest lies in human reportage. Despite initially studying as an architect, I’ve always been more interested in engaging with issues that I feel strongly about, which is why I turned to this style of photography,” explains Pellegrin, on a hotline from his native Rome. “I’ve always wanted to use the camera to investigate and tell stories – like a visual essay,” he adds softly. Such visual essays have included the plight of poverty-stricken children in post-war Bosnia, the AIDS epidemic in Uganda and the US-led invasion of Iraq.

“Photography is much like writing to me,” he enthuses, adding, “It’s a voice. The voice of the photographer and the voice that’s so informed by what we encounter.” Indeed, it's the way in which Pellegrin captures these moments of heightened emotion and circumstance with innate sensitivity, yet a striking cinematic formalism that urges us to react, above and beyond the evocative subject matter which initially piques our attention. “I believe that pictures transform and modify us. They can acquire a life of their own, they carry an intention, as well as the thoughts and spirit of the photographer,” he says.

In a bid to let his “photography speak in more abstracted terms”, Pellegrin predominantly shoots in black and white, a palette that nods to mid-century pioneers such as Robert Capa, who – together with Henri Cartier-Bresson – founded the famed Magnum photo agency that Pellegrin became part of in 2005. Most recently, he has travelled to Libyan coast to report on the escalating refugee crisis, which he has documented in a new photo series entitled, Desperate Crossings. Here, he reflects on the poignant photos and discusses his ever-evolving creative process.

The greatest influences on your creative practice?

“I studied history of art so there’s a strong grounding of that in my work. I also love a diverse range of cinema. I love [Andrei] Tarkovsky, but I also love movies from Hollywood’s Golden Era – that has informed my photography. I think that reading too, can truly transform a person. It allows us to look at things differently, from different perspectives.”

You predominantly shoot in black and white, why?

“For two main reasons. The first being, it follows a long lineage of photographers that I very much admire, such as Josef Koudelka and Eugene Richards, who all work in this way. Also, the abstraction of black and white allows photography to speak in more symbolic terms – colour, sometimes, is all too real.”

"The abstraction of black and white allows photography to speak in more symbolic terms – colour, sometimes, is all too real" – Paolo Pellegrin

You frequently document highly dangerous, war-torn areas of conflict. How do you prepare yourself – mentally, physically, emotionally – for such situations?

“I am frightened all the time. I don’t think I’m a brave person at all. I force myself to overcome my fears. In the Middle East, where I mainly work, it is becoming more and more complicated and dangerous. But over the years I’ve learned to understand my limits – that I cannot put myself in certain situations. It’s especially complex now as I am father of two young girls, which has changed my whole universe, but at the same time I don’t want to negate myself and what I do.”

Do you find it difficult to emotionally detach yourself from such grave situations?

“Enormously. We photographers live in a constant state of schizophrenia because of what we see, what we feel and what we have to overcome. It’s a big emotional presence in our lives, in my life. I don’t think there’s any specific way to deal with it, but it is the life that I chose.”

"There’s a constant tension – a moral, ethical tension – between your role, your function and you as a person" – Paolo Pellegrin

With such exposure to extreme crises, do you worry about becoming desensitised?

“Yes, but in my mind one doesn’t become more detached or cynical – in fact, it’s quite the opposite. I think that being exposed to human suffering or people that live in extreme situations makes me much more sensitive. In this sense it becomes more difficult to photograph, because you become more modest. I recognise the importance that the situation has to be documented, but I’m very careful about how it’s captured. There’s a constant tension – a moral, ethical tension – between your role, your function and you as a person.”

So possessing an increased vulnerability enhances your aesthetic?

“Yes, to a degree. But you want to be more vulnerable because that’s how your photography becomes more human. In a sense you want to become a totally blank canvas so the subject or situation reflects him or itself upon you – you have to be open, innocent and there’s an element of emotional vulnerability.”

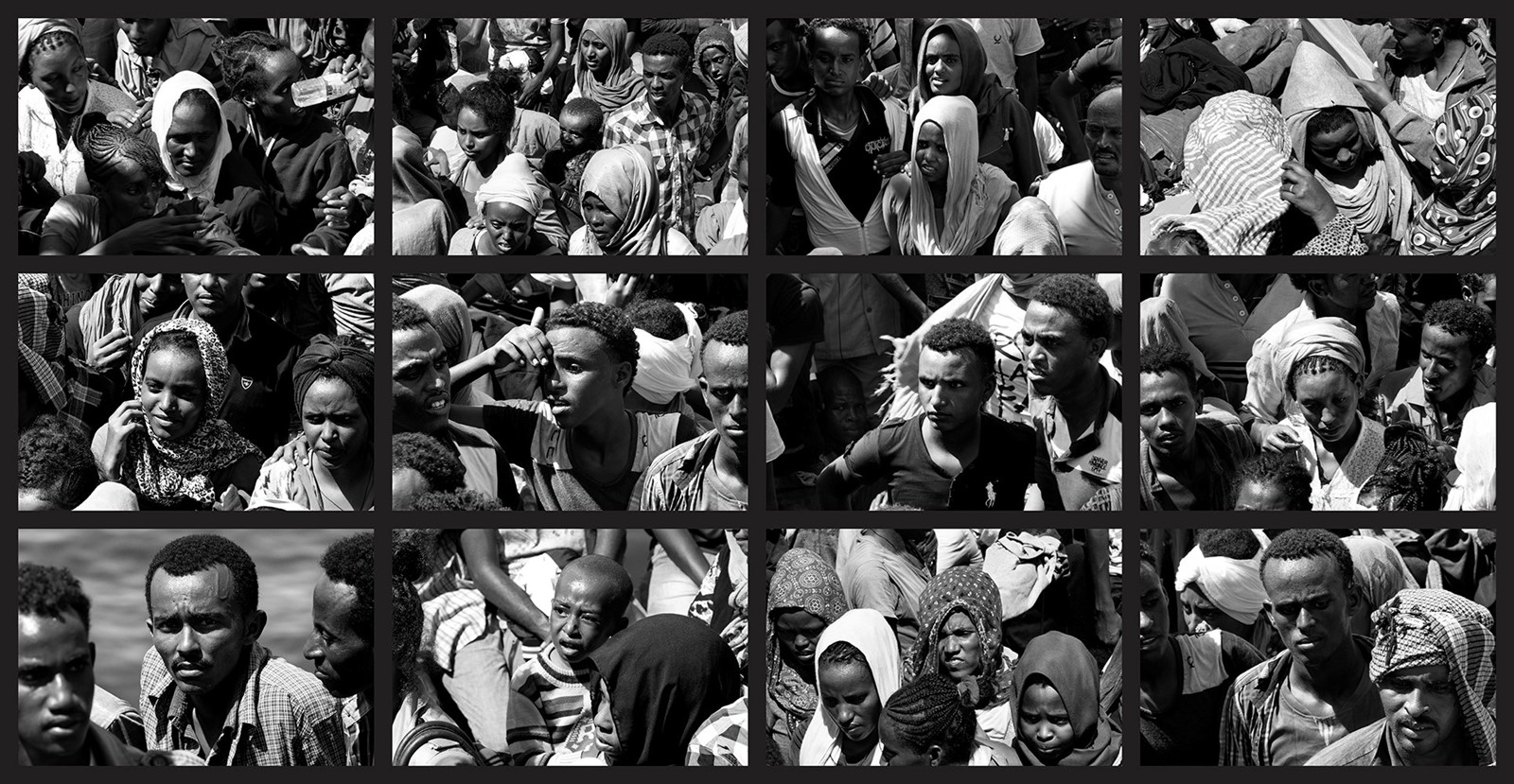

You speak passionately of photos you took in 2015, which depicted an MSF (Doctors Without Borders)-led rescue of Eritrean refugees aboard two boats originating from Libya, bound for Europe. Talk me through this series...

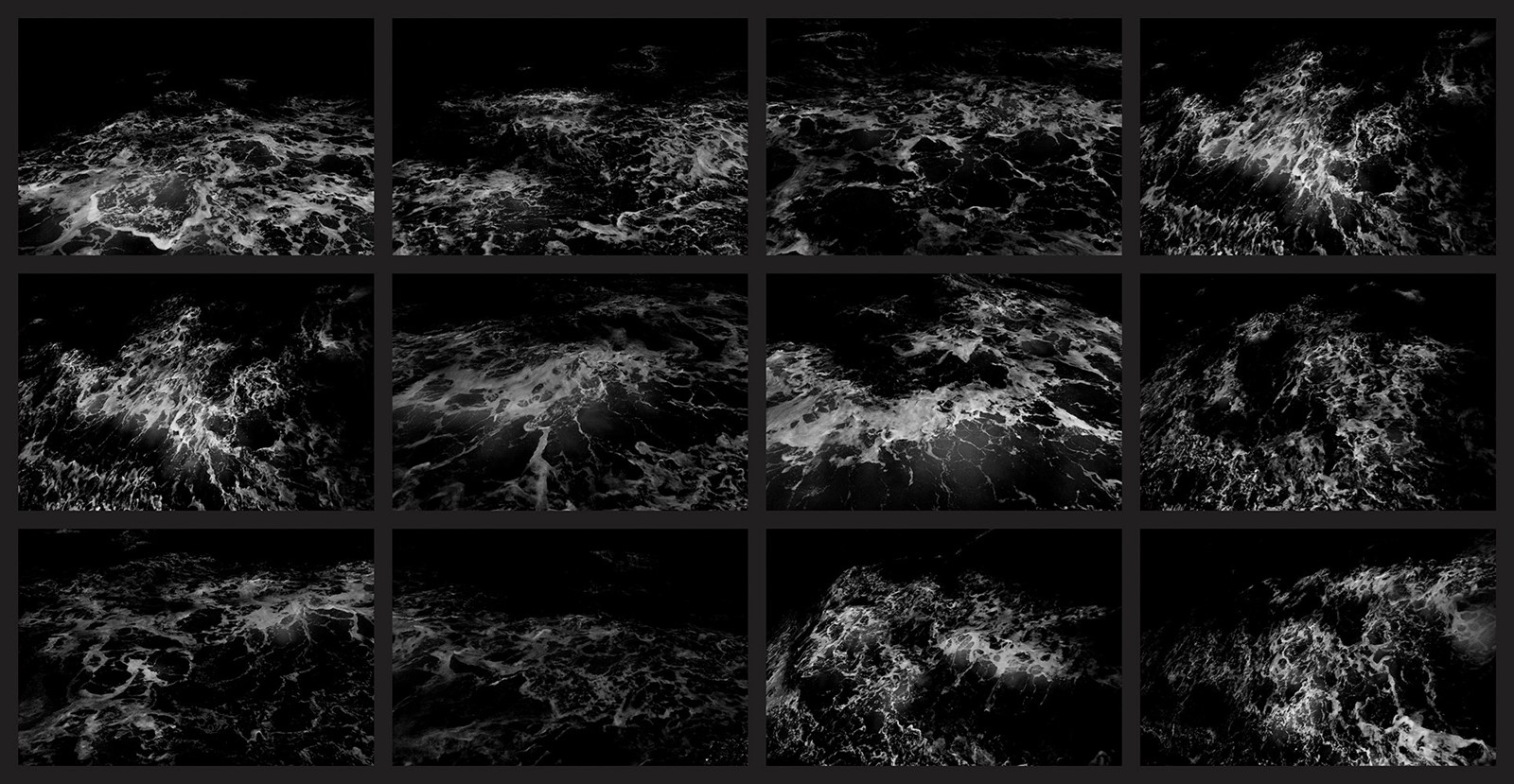

“Yes, well, as we know the situation in Libya is horrific. These refugees have days of navigation ahead of them, yet they have no idea where to go, no compass and no support. Often the boats are badly made, wooden or even Chinese dinghies. They are just told to go north with the hope of being intercepted by one of the Médecins sans Frontières rescue ships.”

Which is exponentially dangerous… So, you boarded the MSF ship, camera in tow?

“Yes. It is very complicated as the chance of disaster is so great; sometimes these wind boats are so small that the radar doesn’t even pick them up. We just saw these dots floating on the horizon through binoculars – which on closer inspection were two wooden boats, which were incredibly full of people. We intercepted them for rescue and I witnessed something completely extraordinary.”

It must have been terribly emotional to see people in such distress and such danger?

“Yes. People were in a very bad state because of the fumes. These two boats were packed like slave ships – it’s so hot; the hull is the most dangerous part of the boat and many people are confined there. There was actually a third boat that had left the same day containing relatives of the two we intercepted, but it was lost. We stayed another day but couldn’t find them…”

With special thanks to Paolo Pellegrin and Magnum photos.