As compelling new exhibition Eye Attack opens at the Louisiana in Copenhagen, we consider five of the artists who propelled op art to the forefront of cultural consciousness

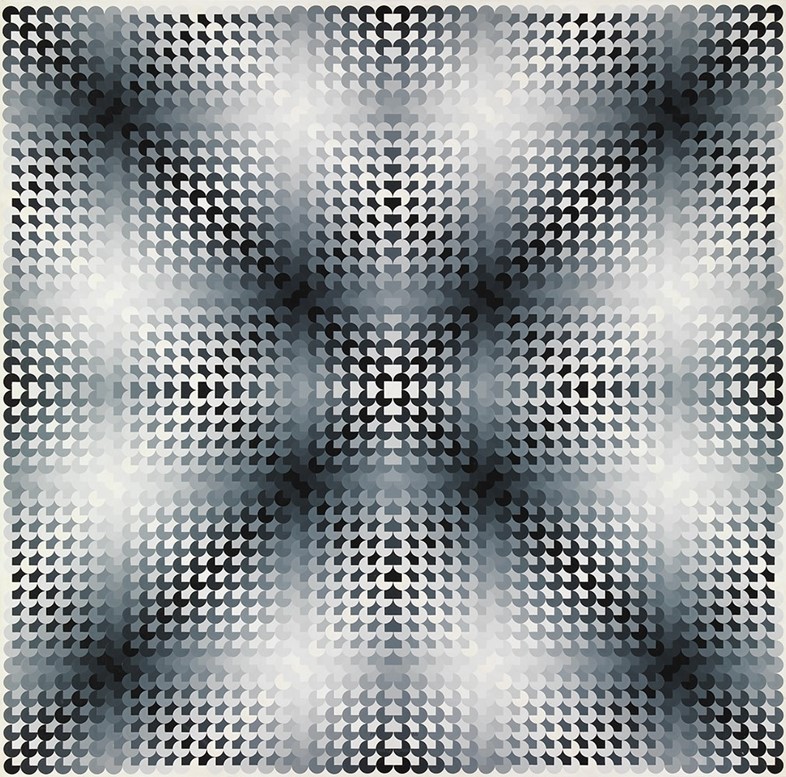

It’s not often that an artistic movement is so visually engaging, exciting and accessible that it permeates popular culture to become synonymous with the time in which it was created. This, however, is very much the case for op art. Also referred to as kinetic art, the style is dependent, crucially, on the viewer – subtle movements in the eye of the beholder give the impression of movement, from swelling and twisting to vibrating and flashing shapes, often using repeating monochromatic patterns. It was initially pioneered by artists including Venezuelan Jesús Rafael Soto and Hungarian Victor Vasarely in the early 1950s, but by the mid-1960s, optical illusions and strong, eye-catching motifs were ubiquitous.

The omnipresence of the movement is due, in part, to the democracy at its core. "We need not leave the enjoyment of a work of art indefinitely to an elite of connoisseurs," Vasarely wrote in 1955. "Present-day art is moving towards more generous forms, which are re-creatable at will. The art of tomorrow will be a treasure common to all, or it will be nothing."

So accessible was the movement that it permeated fashion, design and advertising, becoming a signature for the era in which it originated. Before long, bold checks and geometric shapes had jumped off canvases to infiltrate fashion designers’ studios: André Courrèges introduced large circular cut-outs and thick deckchair stripes to his A-line mini dress shapes, while Pierre Cardin’s spherical mirror paillettes brought an element of movement to fashion editorials and campaigns. It even graced magazine covers, as Gerald Oster’s serigraphic application to the June 1965 issue of Vogue aptly demonstrates. Everywhere one could look they would find geometric shapes, monochrome patterns, and experimental ideas. "It was a marvellous time," Diana Vreeland once reflected. "In the 60s you were knocked in the eyeballs. Everybody, everything was new."

This week, a new exhibition at Copenhagen’s brilliant Louisiana Museum of Modern Art celebrates the wonder of op art in all of its myriad forms. "It [op art] had nothing to do with showing us the world; rather, it was about placing us in it by getting very close to something else – our sensory apparatus itself," the Louisiana explains. "It was an art form that was also an occupation of the senses, a little like the hallucinogens of the same period – but without the acid. An art form that more than anything points directly back to ourselves as sensing beings – with all the uncertainty and instability that follows." Here, AnOther selects five of the movement's most prolific pioneers, from Victor Vasarély to Bridget Riley, and considers their most exceptional contributions.

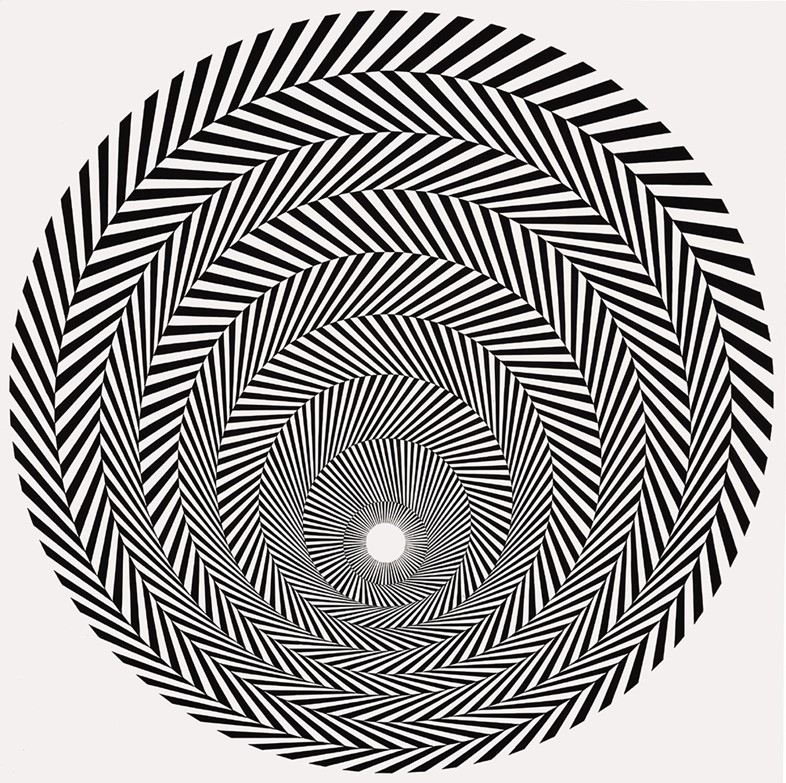

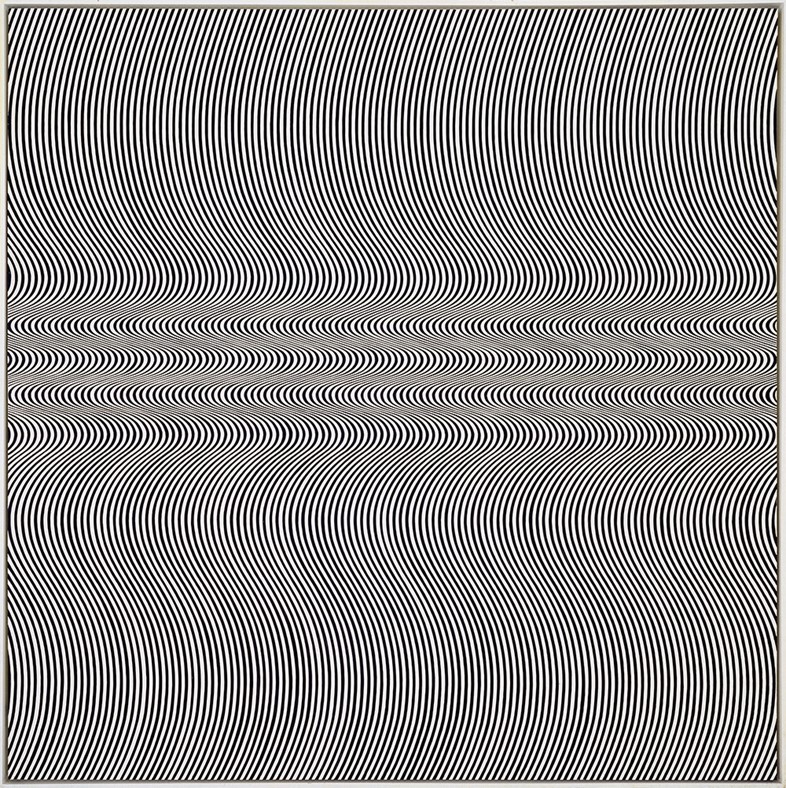

Bridget Riley (1931)

English painter Bridget Riley is the UK’s proudest contributions to op art. Born in London in 1931, she studied at Goldsmiths College and the Royal College of Art and worked as an illustrator at a London-based advertising agency before veering beginning to develop her signature op art styles. She worked often in black and white, composing undulating lines and repetitive forms which tended to create the illusion of colour or movement, and for which she was become the most famous. Now aged 84, Riley continues to work between London, Cornwall and France, as well as curating exhibitions on the likes of Mondrian and Klee, and producing books on her on extensive oeuvre.

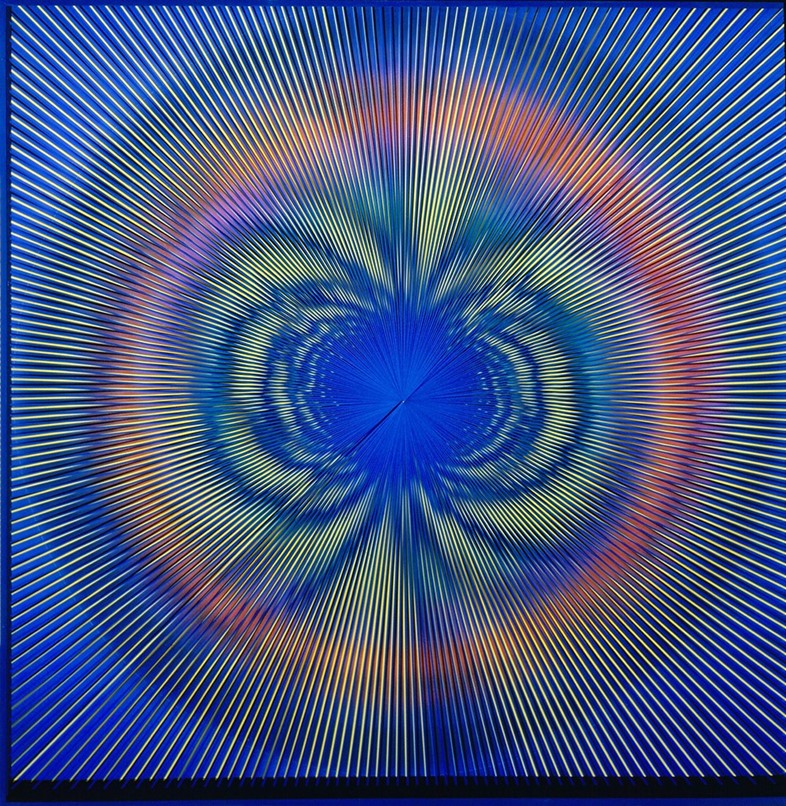

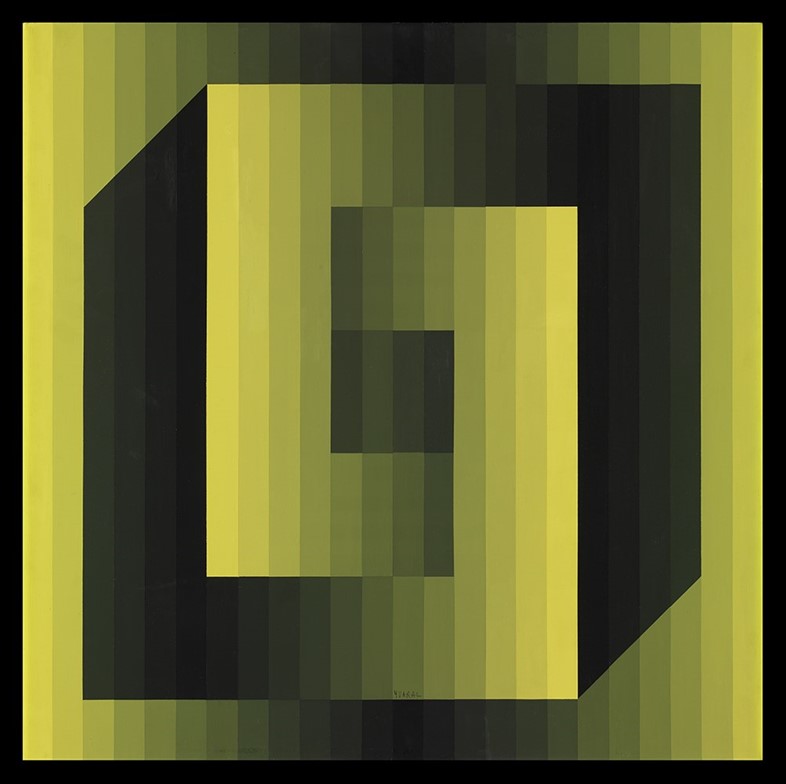

Richard Anuszkiewicz (1930)

One of the foremost exponents of op art, alongside contemporaries Riley and Vasarely, Pennsylvania-born artist Richard Anuszkiewicz was once nicknamed "one of the new wizards of op," by Life magazine. He studied under the prolific Bauhaus-trained artist Joseph Albers, and his contribution to op art is bright, bold and colourful, providing a welcome antidote to the overwhelming monochrome patterns.

Anuszkiewicz' work, alongside that of Vasarely and Riley, was purchased by art collector and dress manufacturer Larry Aldrich, who succeeded on capitalising on Anuszkiewicz’s ideas by designing fabrics based on his compositions. By applying optical illusions to women's bodies, Aldrich and others like him continued the politically charged conversations around sexuality which dominated in the 1960s, when reproductive rights were a hot topic. "The bold, visually disturbing adornment of the female form by illusory pattern, periodic structures, and complementary colour contrasts, carried an undercurrent of aggression that reflected a social and sexual unrest of the moment," the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art explains. "The body itself had become a politically contested site in 1965, centered on legislation over reproductive rights, and the National Organization for Women formed shortly thereafter."

Edwin-Mieczkowski (1929)

For his part, Pittsburgh-born artist Edwin Mieczkowski intensely disliked the term op art. In fact, in 1959, together with a group of like-minded Cleveland-based artists, Mieczkowski founded the Anonima group – a collective which sought to evade fame and material success in favour of experimenting with colour, geometry and perception, as was their shared interest. Unfortunately for the collective, their work provided exactly the complex, refined counterpoint to the rampant abstract expressionism which preceded them that the public desired; by 1964, Europe's wider art community was attributing Anonima with the invention of op art, and lauding them accordingly.

Mieczkowski experimented continually with forms throughout his lifetime. "I was always quite deliberate about not wanting to do just one thing," he once told an interviewer. "This was a conscious decision that I made quite early in my career. Over the years, my work has continued to evolve and change. I was always fairly flexible and never had much difficulty moving on from something I was doing to something new. So I would typically go from one work to another, and every so often, I would make a significant change."

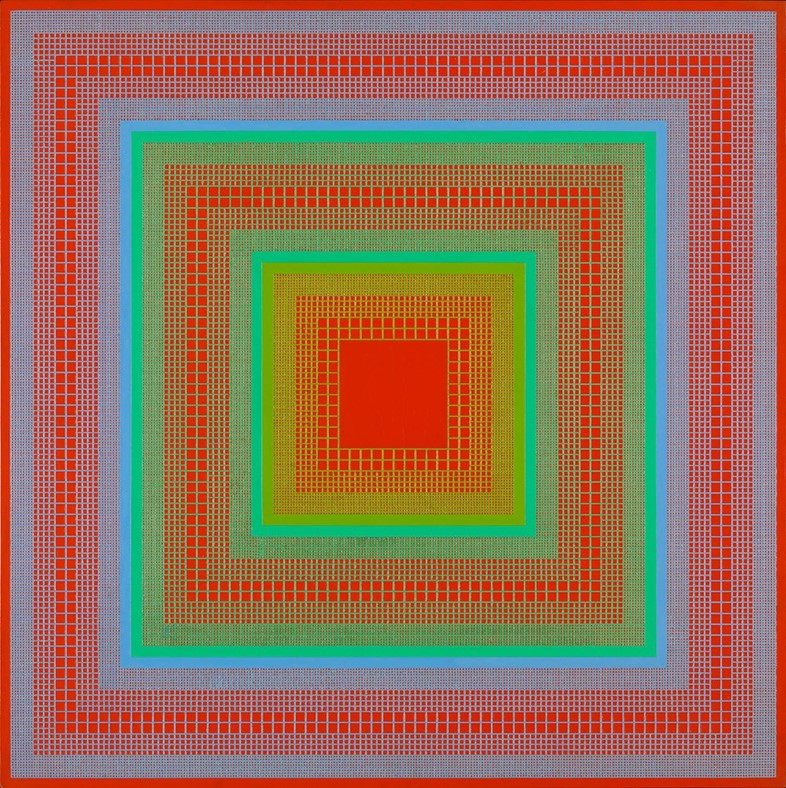

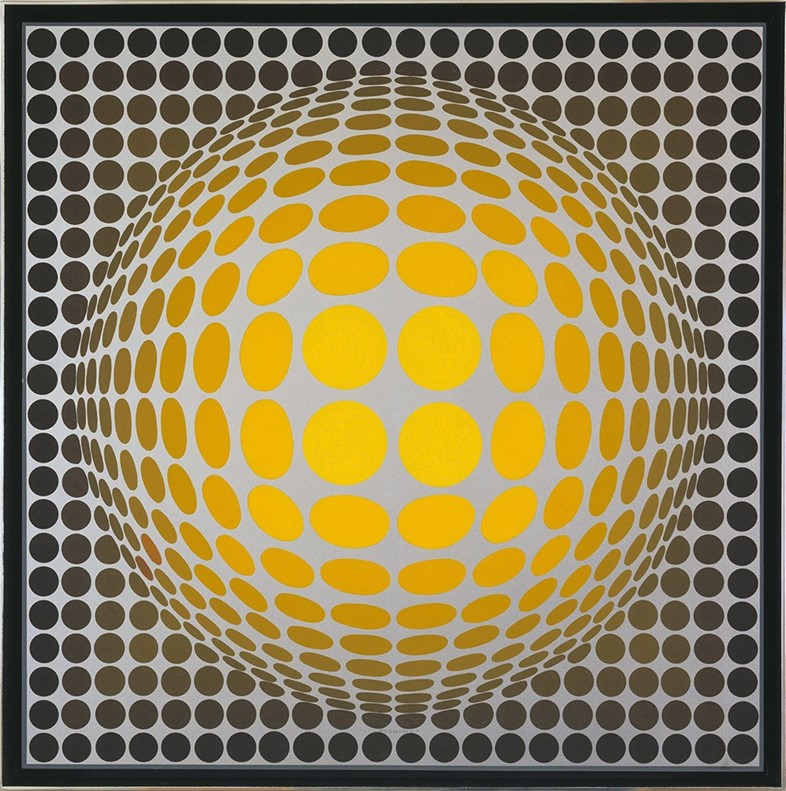

Victor Vasarely (1906-1997)

Victor Vasarely is one of the foremost artists to be included in Eye Attack – and with good reason. Between co-founding a gallery which would champion kinetic art, curating exhibitions, such as a 1955 event called Le Mouvement which would bring artists working within the realm to the forefront of cultural consciousness, and presenting extensive written works on the subject of perspective, he contributed more to the movement than any of his contemporaries, ensuring that ideas around it become firmly grounded in the era. "The art of tomorrow will be a collective treasure or it will not be art at all," he once famously said, determined to ensure kinetic art was available to the broadest audience possible – a service which proved invaluable, as op art motifs became some of the most recognisable of the 20th century.

Jean-Pierre Yvaral (1934-2002)

Jean-Pierre Vasarely, who worked professionally under the name of Yvaral, was the son of Victory Vasarely and associated closely with his father’s groundbreaking work. While Victor Vasarely was considered the 'grandfather' of the movement, Jean-Pierre was very much the wayward son – he worked extensively with computers, in their earliest incarnations, to create the algorithmically composed artworks for which he would later coin the term 'numerical art'.

Yvaral was especially interested in the overlap between digital processes and recognisable celebrity portraits, and spent much of his career processing photographs of icons, Marilyn Monroe for example, to the extent that they were transformed into something completely new. Other pieces used images of the likes of Salvador Dalí and the Mona Lisa, toying with glitches, pixels and digital phenomena to propel them into the digital realm. While his work appears somewhat dated from a contemporary standpoint, Yvaral was incredibly innovative in his use of computers to create artworks.

Eye Attack: Op Art and Kinetic Art 1950-1970 runs from February 4 until June 5, 2016 at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen.