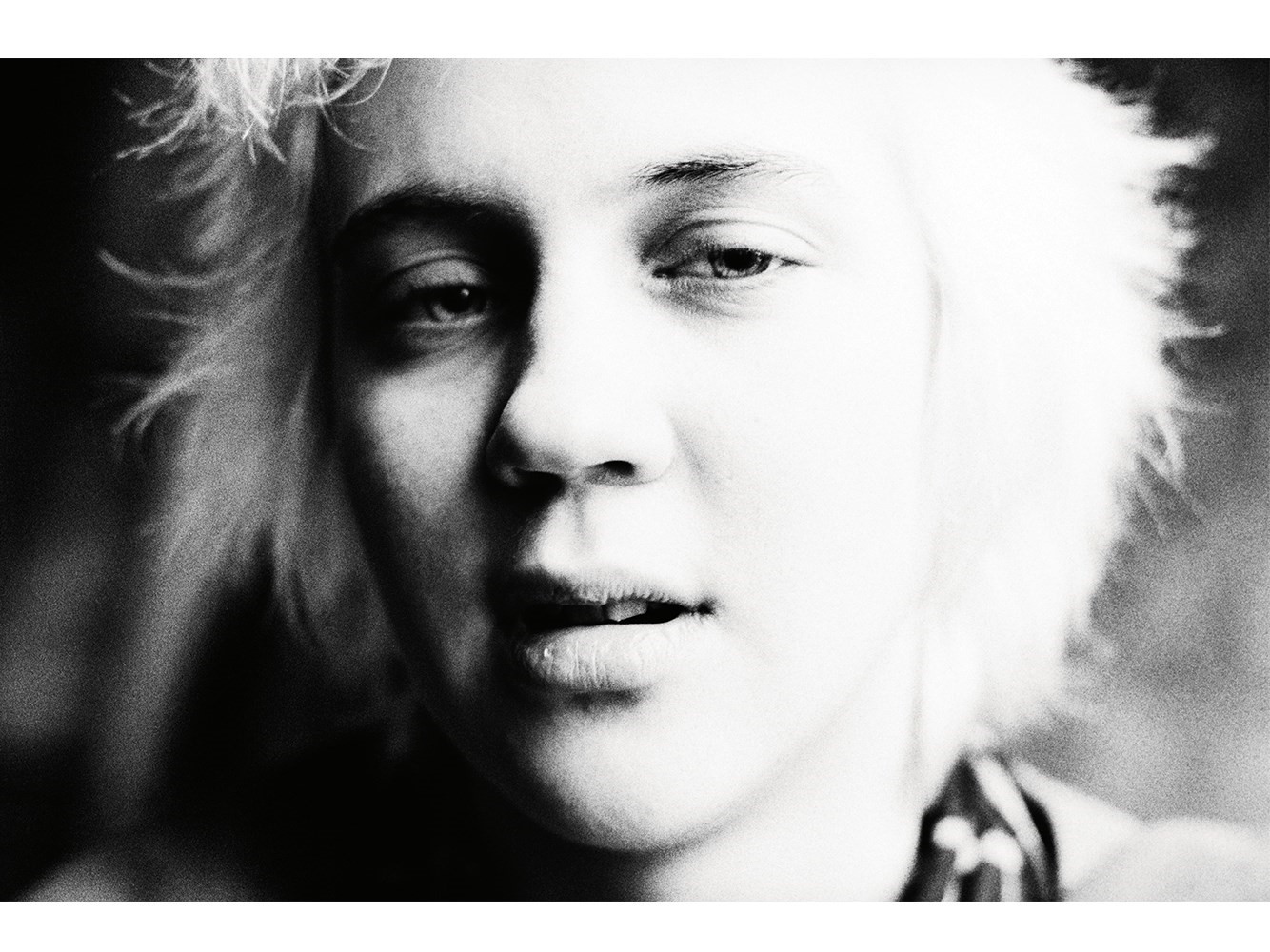

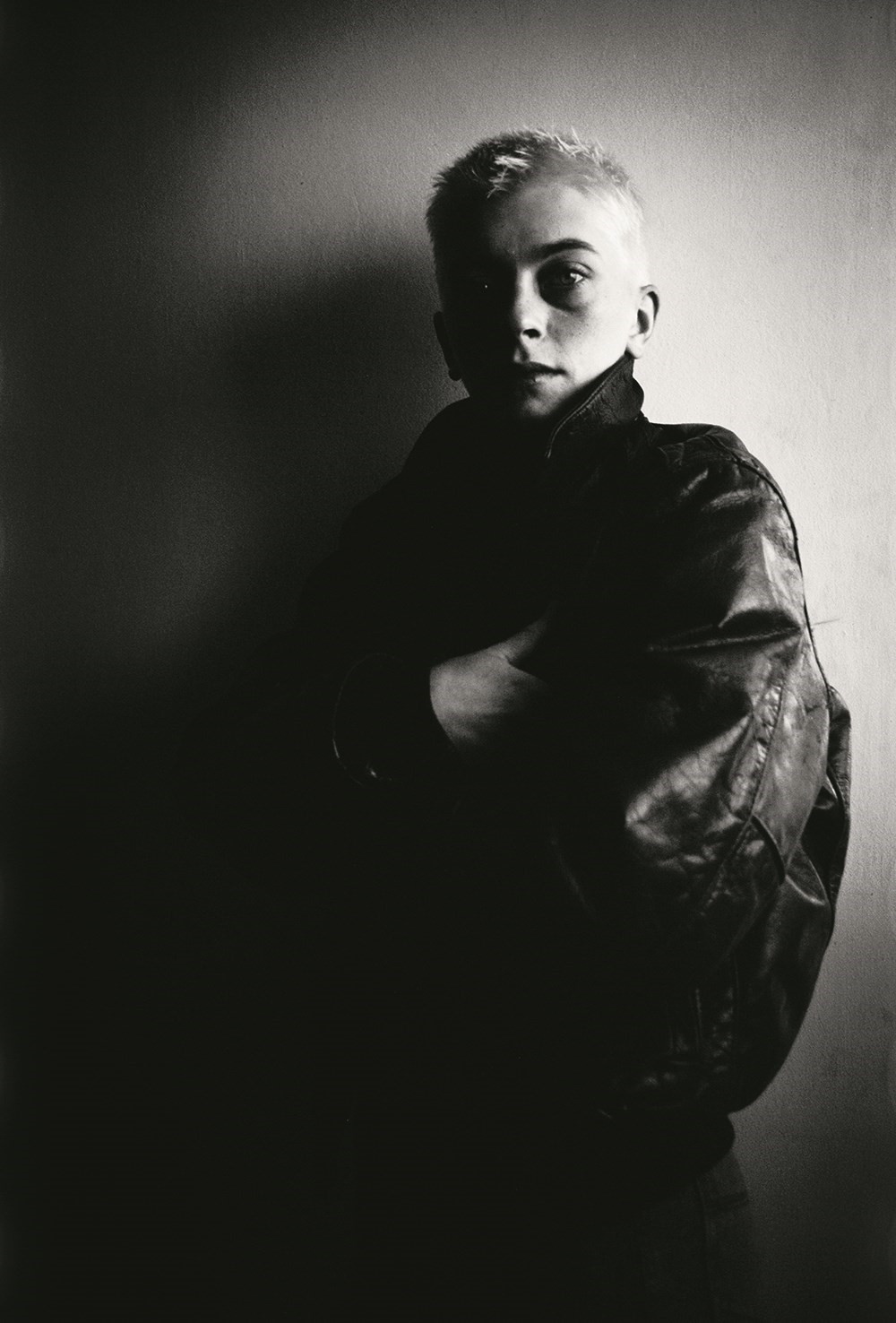

Mark Cawson was in his mid-teens when he came to London from Nairobi in the 70s. Charismatic and beautiful, he fell with little effort into any scene he came across. Everyone knew him as Smiler. The loose narrative he has written of his life skates across fashion, music and art, with heroin as the ribbon that ties everything together. If drugs were one relationship, his abiding passion was photography. He always took pictures, until he couldn’t anymore. Smack won.

Gareth McConnell is also a photographer, at one time a contemporary of Ryan McGinley’s under the auspices of the legendary photo editor Kathy Ryan at The New York Times. But McGinley went in that direction, and McConnell went to hell and back. Heroin again. He’s now a curator and publisher, with his own respected imprint Sorika.

Their paths first crossed 15 years ago, when Smiler came round to McConnell’s place to use his scanner. “I didn’t even know he was a photographer,” McConnell says, but the two images he saw that day haunted him, so much so that, when he was considering projects for Sorika, there was never a question that Smiler wouldn’t be one of them. So McConnell went back to King’s Cross, to track him down. The man he found was fragile, struggling, as he closed in on 60. But McConnell’s commitment was unwavering. The result of that commitment is a book, an exhibition and a limited-edition set of images which, if not exactly making up for Smiler’s years in the wilderness, should at least let the world know who he was and what he did.

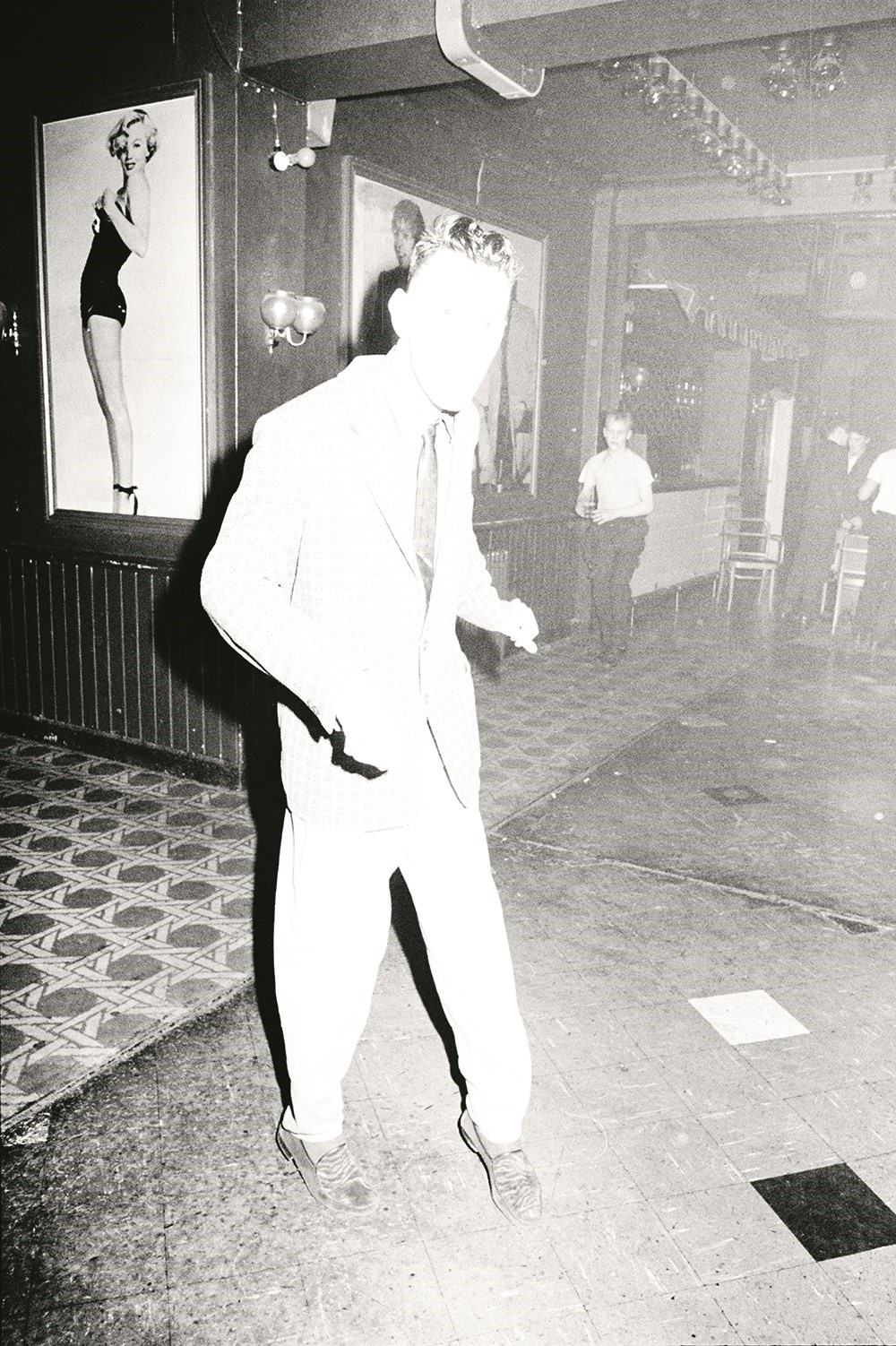

“Smiler has such an eye,” McConnell rhapsodises. “He’s a total artist. I’ve seen a lot of stuff from this era – late 70s to early 90s – and none of it touches the sides of this. It ticks all the boxes: composition, subject matter, lighting, emotional connection, all the things that go into making an amazing experience.” But as much as he waxes lyrical about Smiler’s “naïve perspective” and “superb composition” and “the painterly nature of his photographs”, the primary lure of the pictures for many viewers will probably lie in something else. As McConnell says, “He was there.” Yes, Smiler was ‘there’, in the middle of this dark, long gone world, and we weren’t. It’s the irresistible authenticity of participation, rather than observation.

An entire genre of photographic books has sprung up around lost worlds – and they keep on coming. Like Simon Barker’s snapshots of the Bromley Contingent at play, collected in Punk’s Dead, and, at the other extreme, A Chequered Past, Peter Schlesinger’s visual record of London’s beau monde in the 60s and 70s. Or Tod Papageorge’s photos of Studio 54, which, even though they make the club look like Dante’s fifth circle of hell, still have a clammy ‘you-weren’t-there-but-now you-can-be’ intimacy. Or Mike Brodie’s remarkable riding-the-rails diary A Period of Juvenile Prosperity, though that is something of an exception, because it is more often some aspect of nightlife or club culture that is the focus. Anything can happen undercover of darkness. In particular, clubs from the way-back-when are now celebrated as crucibles of culture – Blitz, Paradise Garage, 54, Le Palace, Mudd, Area, Taboo, the Veil, and on and on – so photographic records of their existence often parade fleetingly familiar faces in extreme situations.

More than that, these records, reflecting the naturally hermetic exclusivity of nightclubs, their courting of socially marginalised tribes and their finite quality – so often evocative of the transience of youth and doomed beauty – have created a series of glamorous, romantic time capsules that are quite the equal of any decadent coteries of the past into which lotus eaters are wont to dreamily project themselves. The single difference here is that there are actual photos to give us an indication of how people looked and moved and behaved in the endless stream of casual moments being fed to us by all these publications. In a digital era obsessed by unreal representations of ‘reality’, such analogue imagery seduces with its realness, even when its content is surreal. And it also feeds an innate through-the-keyhole curiosity. “See? That’s what was going on,” our inner voyeur whispers. “Look what you missed.” (Or – sometimes – “You didn’t miss much after all.”)

For all that, there is something more to Smiler’s story. When McConnell talks about him, I can’t help thinking of Vivian Maier, henceforth the patron saint of all artists who have been lifted out of anonymity by one visionary championing their legacy. Maier was a nanny whose obsession was the act of taking a photograph, eventually hundreds of thousands of them, few of which she ever developed. The contents of her storage unit were put up for auction in Chicago when she stopped paying her bill. That was how estate agent John Maloof came to buy a box of negatives, on the hunch that there might be something relevant to a local history he was working on. Maloof’s stewardship of Maier’s work has turned her into an art world sensation. She never lived to see any of it, and people who remember her say she would have loathed the attention. Still, Maier’s ‘career’ is one of the most striking correctives in living memory.

And its particular relevance to McConnell and Smiler is this: the narrative is as much about the curator as it is the artist. “I don’t feel any ownership,” McConnell insists. “I’m not doing it as a favour to Smiler. I think this work needs to be seen.” But it’s the curator’s eye that has winkled out, from the mass of available material, the story told by the 25 images on exhibition at the ICA. Though Smiler also photographed still-lives and classic nudes, McConnell has selected “the punks, the drugs, the squats, all the people that emerged from the cultural capital in that particular scene”. There are pictures of Peter Doig’s studio and Keith Allen’s wedding, for instance: “But I didn’t want it to be celebrities,” McConnell adds quickly. There are also pictures of London’s first McDonalds, of George Bush’s visit to London, of an ATM being installed, which implies a polemical subtext. McConnell denies that. Similarly, he separates Smiler from autobiographers like Nan Goldin and Corinne Day whose source material is admittedly very similar. “It comes from a different place,” McConnell again insists. “Smiler wasn’t documenting a scene, he just loved photography.” If that sounds a little disingenuous, it pays to remember that it is McConnell who has looked at the work and created the document we’ll see at the ICA. “Everyone’s a curator now,” he shrugs. “It’s an archaeology. I enjoy people, I enjoy seeing stuff that has innocence, love, chance, a lack of cynicism…”

And, he concedes, he has his own romantic attachment to the material. “A lot of my youth was spent running round like that,” McConnell says. His own life was not derailed by addiction to the extent of Smiler’s (who in 1991, around the time he stopped taking pictures for good, wrote, “I am homeless again in a far more unforgiving world”), but McConnell certainly looks like he has lived hard every one of his 42 years. And, as it does with most recovered junkies, the old life clearly still has a hold on him. However perverse the romance is, it’s hard to beat. You can hear it in McConnell’s voice when he talks about Smiler. “I don’t want to mythologise him but he’s the real thing,” he says admiringly. “People want to posture they’ve lived the life he’s lived.” And if that is one hell of a for-better-or-worse proposition, it has fallen to McConnell to make art of a life on behalf of someone who can’t do it for himself.

This article appears in the A/W15 issue of Another Man.

Gareth McConnell will host a book signing to celebrate the second edition of 'Smiler' at Donlon Books, London on Thursday 10th March 2016 from 7 – 9pm.