To mark the opening of a major retrospective of Strand’s work at the V&A, we celebrate the remarkable life and creative legacy of the photo and film pioneer

Paul Strand (1890–1976) is widely revered as one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century. He carved out the path for American modernism and with it, the way that documentary photography is practiced today. He was a fundamental figure in the recognition of photography as an art form, dedicating his entire life to the medium and its different permutations. Over the course of his career, he proved himself not only an incredible portrait, still life and abstract photographer, but also a pioneer in the development of photography books, a committed political activist and an innovator in the field of motion pictures.

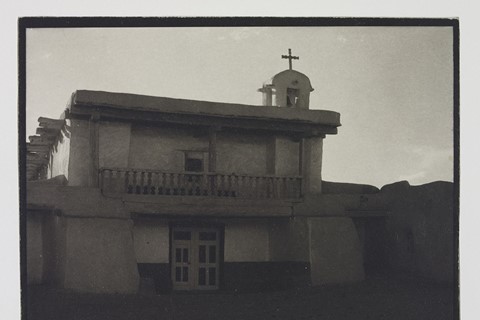

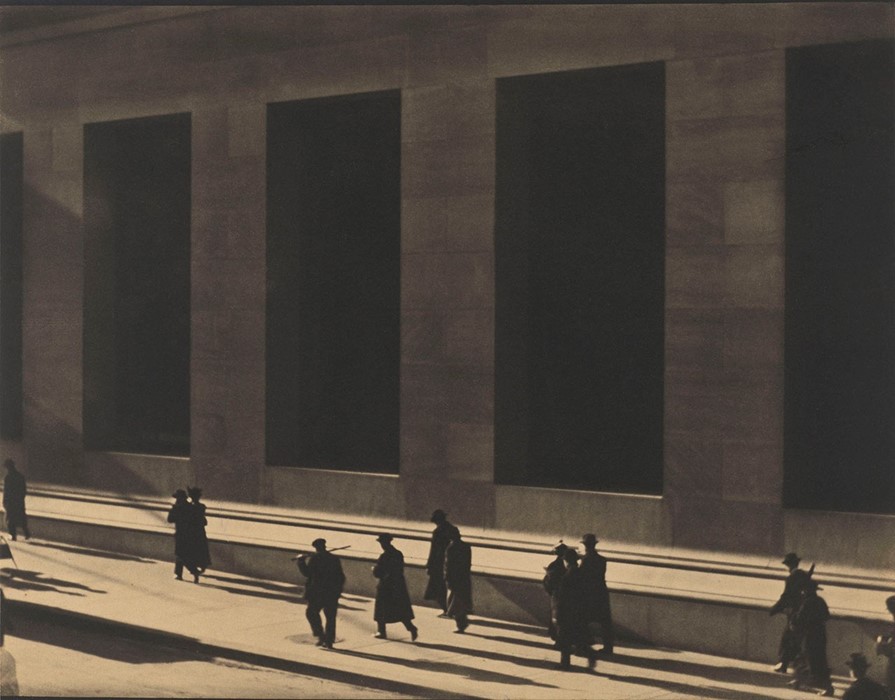

This month marks the opening of Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London – the first retrospective of the American artist's work in the UK for over 30 years – offering a rare chance to appreciate the full scope of Strand’s life work with over 200 objects on display. From vintage prints of his street photography in 1910s New York (including his early masterpiece Wall Street, 1915) to images of rural France in the 1970s, radical explorations of abstract photography, human form and moving image (Strand’s 1921 short documentary Manhatta is largely thought of as the first avant-garde film), the show traces Strand’s career as a photographer while fostering an awareness of his role as an international polymath. To mark the opening of the exhibition later this week, AnOther presents a five-point guide to the work and legacy of the trailblazing photographic modernist.

1. He experimented with different forms of photography before finding his own style

Born in New York City to Czechoslovakian parents, Strand was given his first camera by his father at the age of twelve. However, he didn’t develop an interest in photography until later in high school, when he enrolled in a photography class taught by sociologist and photographer Lewis W. Hine. It was Hine who first introduced Strand to photographer and future mentor, Alfred Stieglitz at the latter's celebrated gallery 291. That visit, along with the influence of Hine’s progressive outlook, represented a pivotal moment for Strand who, at 17, declared his intention to become “an artist in photography.”

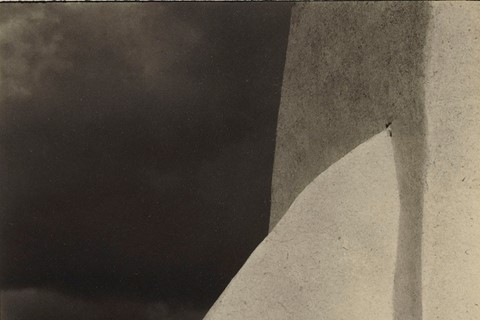

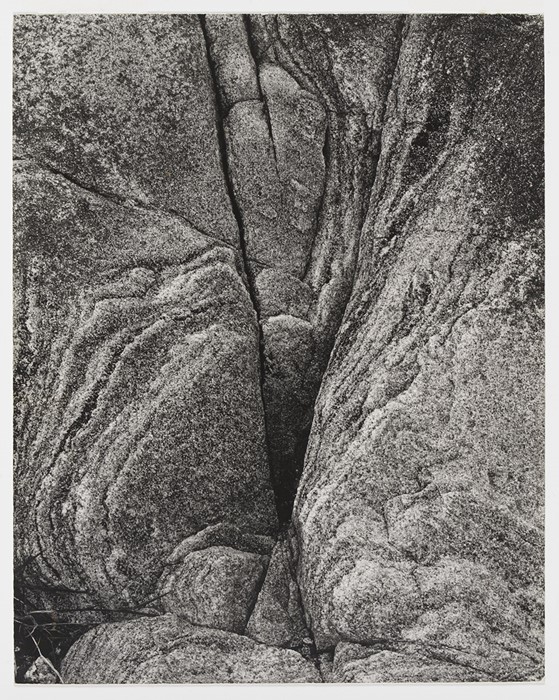

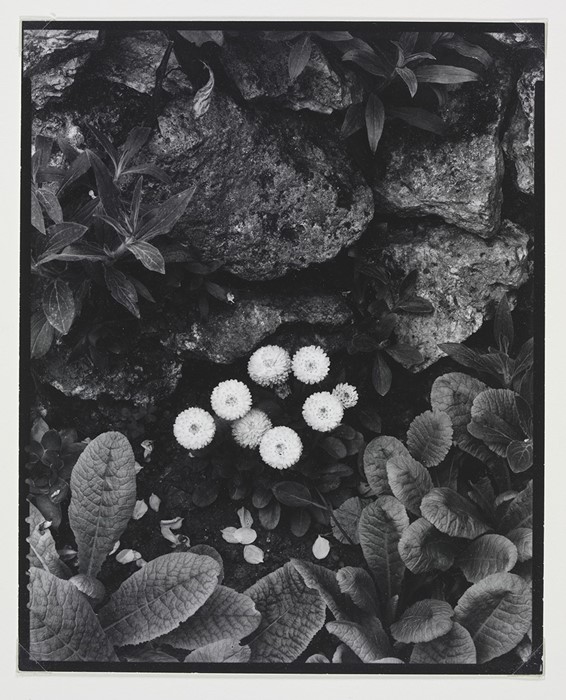

By 1911, Strand had joined the Camera Club of New York, going on to develop a fascination with the image manipulation techniques of Pictorialism. It was at this time that he began to experiment with diffused light and soft-focus lenses in an attempt to stress the aesthetic properties of photography and make his images look like paintings. While Stieglitz championed the work of Pictorialists at 291, his own work pioneered a new photographic style whereby image manipulation was rejected in favour of a sharp and detailed picture. This new approach came to be known as 'straight photography' and was later adopted by Strand himself. Like Strand, Stieglitz made no distinction between photography and fine art and often showed the work of Cézanne, Matisse, Braque and Picasso at his gallery. Captivated by the cubist aesthetic, Strand set out to experiment with abstraction within his photography. From shadow plays on a front porch to close-ups of stoneware, Strand’s abstract years were crucial in the development of his picture-building skills.

2. He was one of the first to use the candid-camera technique

Having grown up in New York, Strand was naturally drawn to the dynamism of the city and its people. “I suddenly got the idea of making portraits of people the way you see them in New York parks – sitting around, not posing, not conscious of being photographed,” he stated in a 1974 interview. Driven to document his city with complete photographic objectivity, he created a means of shooting his subjects candidly. He worked out that by screwing in a false lens to one side of his camera pointing ahead while concealing the real lens under his arm facing his subjects, he was able to achieve such result. Most of his portraits were shot that way, including the seminal 1916 image of a blind street beggar (Blind), now an icon of early American modernism. A far cry from his soft pictorialist work, his New York portraits often revealed the strains of living in the city. However, Strand never questioned the morality of what he was doing. “I always felt that [...] I was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process,” he once said. In 1916, his New York photographs were exhibited at 291 and published in leading photographic magazine Camera Work, marking the beginning of Strand’s commercial success, along with his shift into photographic realism.

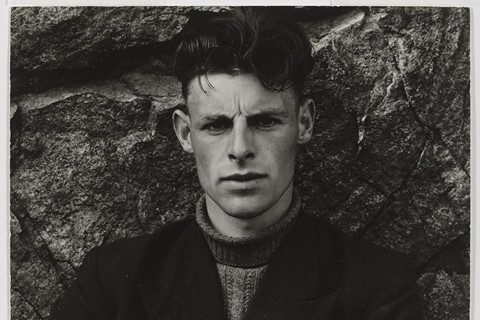

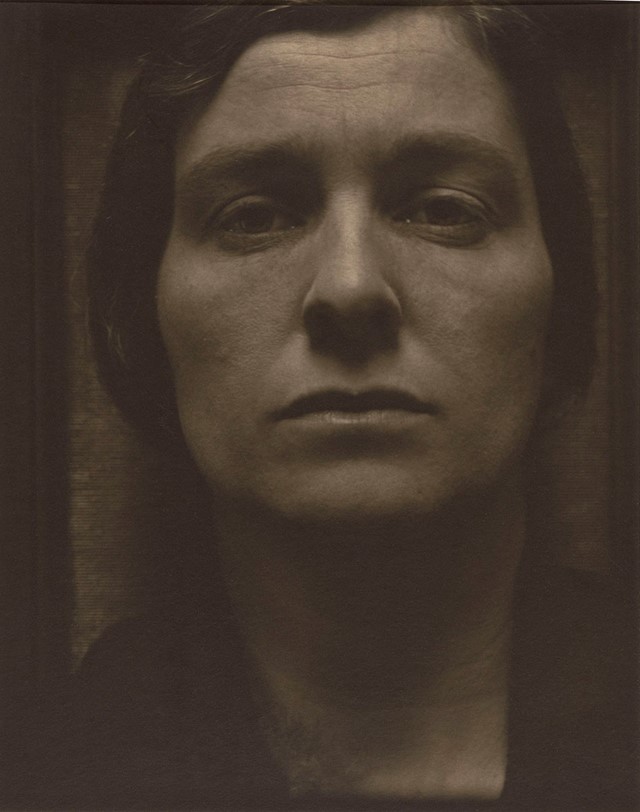

3. He analysed his subjects with astonishing clarity and detail

A few years later in 1919, Strand purchased a large format 8 x 10-inch view camera that he believed possessed the right proportions of a picture. His new images, which he printed on expensive platinum paper, were hard-edged and astonishingly clear, with rich tonal values and deep blacks. Shortly after, he married artist Rebecca Salsbury and acquired an Akeley, a highly mobile movie camera designed to specifically capture wildlife. In his close-up studies of his first wife and the Akeley camera, Strand carefully examined and captured every curve and shadow, revealing a painstaking attention to detail. Comparing a photographer meticulously analysing his subject to a scientist researching the world in which he lives, Strand expressed that “the measure of [an artist's] talent – of his genius, if you will – is the richness he finds in such a life's voyage of discovery and the effectiveness with which he is able to embody it through his chosen medium.”

4. He was also a prolific cinematographer

Strand first experimented with filmmaking in his early 30s, when he collaborated with artist Charles Sheeler on Manhatta, a short silent film documenting day-to-day life in 1920s New York. However, what started as a curiosity soon became a financial necessity, Strand's very particular brand of photography proving hard to sustain financially. During his time as an X-ray technician in the Army, he often filmed surgical operations and off the back of that was offered a job as a cameraman at a small company producing medical films. Although that particular job fell through, Strand’s career as a cameraman continued and for the next ten years he made a living shooting sports events and action sequences for Hollywood movies. By 1937, filmmaking had become his full-time job. Strand had also become increasingly political in his work and focused on social documentary as a way to report on the life of his time. During his time at progressive film studio Frontier Films, he shot Redes, a semi-fictional film about poor Mexican fishermen, co-directed the 1942 anti-labour film Native Land and produced Henri Cartier-Bresson’s first film Return to Life, a documentary on medical relief during the Spanish Civil War, among many others.

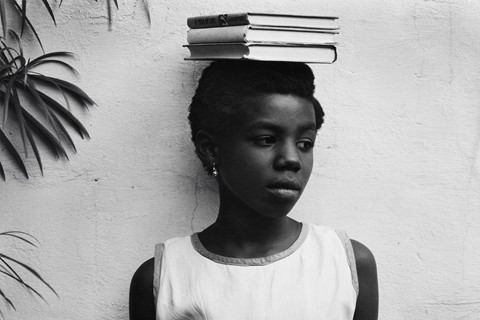

5. He had an enduring obsession with village life

One project that had always sat at the back of Strand’s mind was a book about a village. His intention was to use photography to show the reality of village life and its inhabitants. However, after the anti-communist efforts of McCarthyism caused a number of his former colleagues to be blacklisted as dangerous radicals, Strand decided to distance himself from America’s current intellectual climate and consequently turned to Europe. In 1951, Strand and his third wife Hazel, also a photographer, travelled to France in search of the right village. There, although unable to locate the rural hub he so envisioned, Strand befriended poet Claude Roy with whom he would later publish a book of his photographs of French countryside, titled La France de Profil.

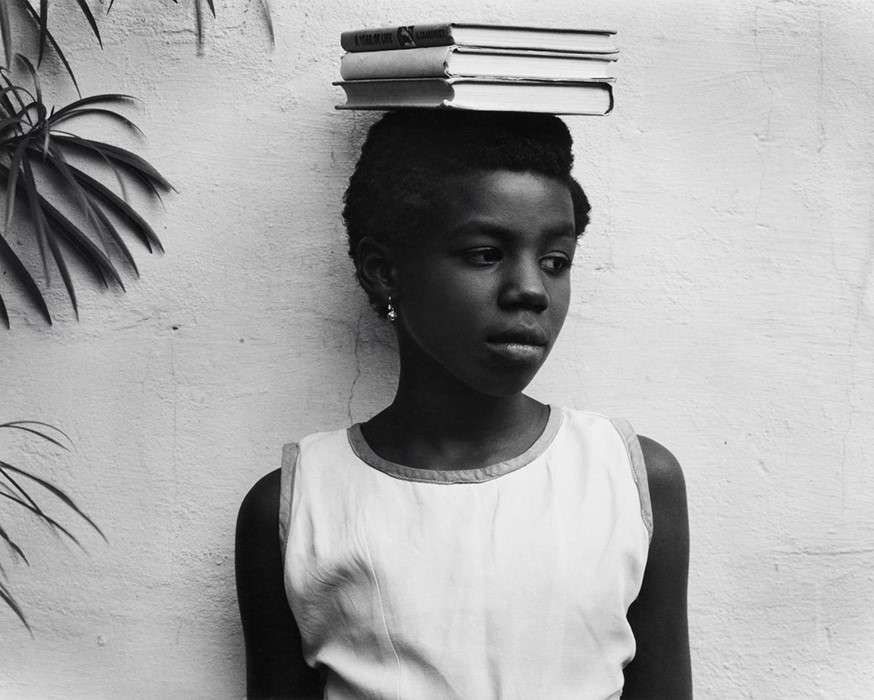

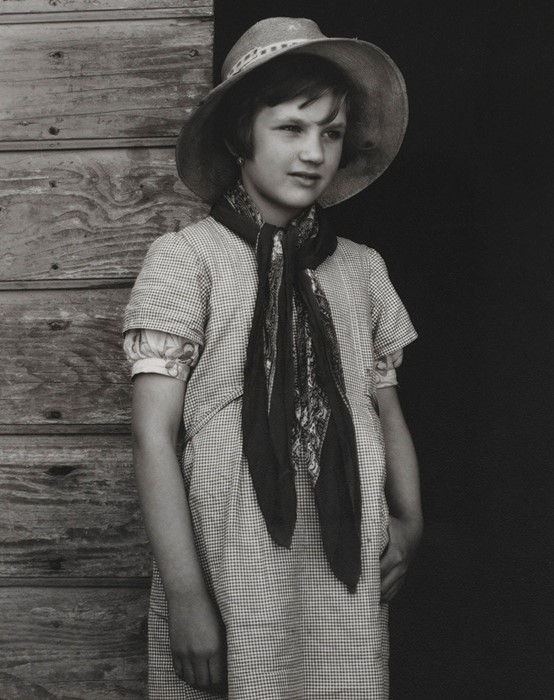

The Strands eventually found their long-sought village a year later in Italy. Italian Neorealist screenwriter Cesare Zavattini had agreed to collaborate with Strand on a book about his hometown of Luzzara, in the Po River Valley. The couple spent two months photographing the village and its inhabitants; the resulting photo-book, titled Un Paese, Portrait of an Italian Village, was published in 1955. Angela Secchi, who featured in Strand's arresting portrait, Farmer’s Daughter, as a nine-year-old girl, recalled how uncompromising Strand was in his vision for the series. “I was shy and a bit frightened by Strand’s seriousness," she said. "It was the first time I had been photographed or had even seen a camera. My aunt had dressed me in my Sunday’s best but that wasn’t what Strand had in mind. He grabbed a large hat off my uncle’s head and put it onto mine, he then took my uncle’s scarf and an old, rumpled smock and told me to wear it on top of my dress. He wanted me to look like a poor country girl.” Regarded as one of Strand’s most expressive and celebrated photographic collections, the book offers an unaccountably modest portrayal of post-war rural Italy and summarises Strand’s vision of an eternal old world.

Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century is at the Victoria and Albert Museum from March 19 – July 3, 2016.