We revisit the supermodel's reflections on the German re-education programme and collecting contemporary art, from AnOther Magazine S/S11

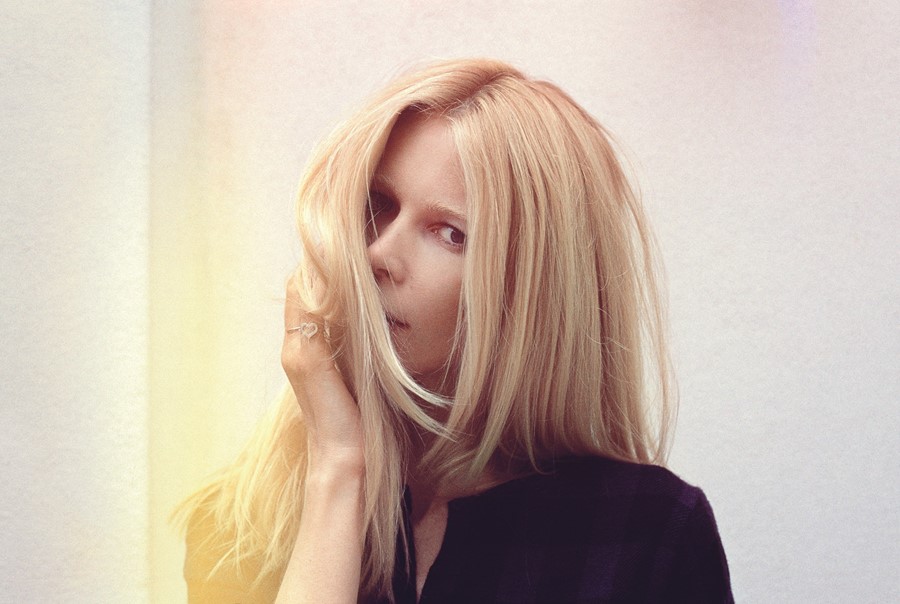

Every collector has the one that got away. Claudia Schiffer’s is probably the huge Basquiat canvas Larry Gagosian offered her years ago for $20,000. She turned it down because her flat in Paris was too small. A shortage of wall space isn’t likely to be a problem she’ll ever face again, even if the rooms of the Notting Hill house she shares with husband director Matthew Vaughn and their three children are already ceiling to floor with a provocative sampling of contemporary art. Yes, there is an impressive Warhol (Gun – a copy of it window dressed Mark Strong’s penthouse in Vaughn’s superhero comedy Kick-Ass) but more intriguing are pieces like the lyrical Kiki Smith portrait, or Dan Colen’s Bird Shit painting. Amidst them all is a Steven Meisel group shot from the early 90s of the handful of models who became modern icons while turning the fashion industry on its head. Then, Schiffer was The Blonde. Now, two decades later, she’s still snaring magazine editorials and advertising campaigns. She’s also launched the Claudia Schiffer Cashmere collection, and she’s clearly a player in the art world, with an open mind and a good eye for the new. She’s got great taste in boys’ names, too.

Tim Blanks: Is your son named after Caspar David Friedrich?

Claudia Schiffer: No, but we did look at the spelling, and thought it was good.

TB: Did they show you Friedrich’s art at school?

CS: Yes, but the people who were really in fashion when I was a teenager in the 80s were Joseph Beuys, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, all the artists who were really inspired by the second world war.

TB: What kind of school were you at?

CS: I was at a “gymnasium”. If you got to those schools, you go to university. My school was very much into art so there was a lot of talk about art inspired by the war. Richter, for example, had a famous picture of his uncle Rudi in his uniform, and also all his images of towns that were destroyed by the war. We were taught by an older generation of teachers who debated whether you could even take these artists seriously.

TB: For people your age, was art a way to deal with what had happened?

CS: Exactly. In Germany back then, there was a lot of re-education about the second world war. We were taught exactly what happened in all its gory detail, and a lot of it was presented in art, as a way of showing that now you have to feel bad so it will never happen again. But it reached a point where we were shown these images and classmates of mine would faint.

TB: And would you go home and ask your parents what they knew about it?

CS: I remember going home thinking, Jesus, this is more horrible than I ever thought it was. My grandfather had a big publishing firm and he was hired after the second world war to re-educate the Hitler Youth, after the camps. So my father knew a lot about it.

TB: When I saw the last Anselm Kiefer show at Gagosian in New York, it was easy to see how transgressive the work must have been when it was first seen in Germany.

CS: I think there’s been a differentiation between Baselitz, Polke, Richter, who put all their emotion about the war into their art, and people like the Bechers, Gursky, Struth and Demand, who are the opposite. Their work has no emotion. It’s dry and analytical. It’s like they’re saying, “I’ve got nothing to do with that, it’s a different generation.” And that’s correct. They weren’t around, they don’t need to be influenced.

TB: Do you identify with that way of looking?

CS: I do, in the sense that you’re so shocked by what happened, but still, it’s nothing to do with you. But when I look at the Bechers’ work, for example, it’s very much how I remember my own youth and the 80s.

"When my husband proposed to me, he had a painting made by Ed Ruscha, one of my favourite artists of all time. It said 'Marry Me'" – Claudia Schiffer

TB: Was art something that absorbed you early on?

CS: I was intrigued by the debate about who was a real artist. But I was more interested in tennis and piano playing and lots of sports.

TB: Is that what you would have done with your life?

CS: No, my father had a law practice. I used to sit in on a lot of his cases and it just seemed that was what I had to do. I would have been a very good lawyer because I can think out of the box but at the same time I’m quite organised. Thank God I never did it. I don’t think I would have liked it. My biggest dream was always to move to Paris one day. I didn’t know it would be as a model because I never wanted to become one. I was 17 when I moved there. I was living in the Marais, and there were lots of little art galleries. I remember a Warhol exhibition of his cat drawings. I bought the postcards thinking, one day I’ll be able to afford one.

TB: Did you ever get your Warhol cat?

CS: No, but I did get a butterfly from the Endangered Animals series. I was told they were the least important Warhols but I said, “I don’t care, I love it and I’m never going to sell it anyway.” Later on I came across the Gun. I hate crime, I hate anything to do with guns, but there was something about that image that I thought was a reflection of Warhol in America. When I was young, I imagined I was like Nico, who was German and who modelled for Chanel. That’s me! I could have been in Andy Warhol’s Factory!

TB: What pictures would you most like to own now?

CS: They’re all really large. One of Andreas Gursky’s images of the Rhine, a Candida Höfer picture of a German library, one of Thomas Struth’s night skies. The reason why I love them is that they remind me of my German roots. Downstairs, I’ve got some small photos by Struth of Düsseldorf, where I used to go shopping with my mum. They’re not particularly special, but I love them. It’s just that memory – and every year, it becomes more important.

TB: What’s the picture you’d rescue in a fire?

CS: When my husband proposed to me, he had a painting made by Ed Ruscha, one of my favourite artists of all time. It said “Marry Me”. I had Ruscha make the answer, “Yes”. He worked quickly.

This feature originally appeared in AnOther Magazine S/S11.